Ukraine war: How TikTok fakes pushed Russian lies to millions

- Published

Anastasiya Shteinhauz and her father Oleksiy Reznikov, Ukraine's former defence minister, were both targeted with false claims

A Russian propaganda campaign involving thousands of fake accounts on TikTok spreading disinformation about the war in Ukraine has been uncovered by the BBC.

Its videos routinely attract millions of views and have the apparent aim of undermining Western support.

Users in several European countries have been subjected to false claims that senior Ukrainian officials and their relatives bought luxury cars or villas abroad after Russia's invasion in February 2022.

The fake TikTok videos played a part in the dismissal last September of Ukrainian Defence Minister Oleksiy Reznikov, according to his daughter Anastasiya Shteinhauz.

The BBC has uncovered nearly 800 fake accounts since July. TikTok says it was already investigating the issue , externaland says it has taken down more than 12,000 fake accounts originating in Russia.

'Villa in Madrid'

Ms Shteinhauz told the BBC she found out about the Russian disinformation campaign when she received a surprising call from her husband while on holiday.

"OK, so now you've got a villa in Madrid," he told her, before sending a link to a TikTok video narrated by an AI-generated voice that claimed she had bought a home in the Spanish capital.

Ms Shteinhauz initially dismissed the video as a one-off, but the following morning she was sent a similar TikTok clip alleging she had bought a villa on the French Riviera. The videos had been circulating among her friends before finally reaching her husband.

Videos on TikTok falsely accused Mr Reznikov and his daughter of buying luxury cars or property in Europe during the Ukraine war

Ms Shteinhauz says she does not own property in Spain or France or "anywhere else outside Ukraine".

BBC Verify also traced the pictures of the houses in Madrid and Cannes to two local property websites and they were both still for sale.

Other videos directly targeted her father.

Co-ordinated effort

The videos sent to Ms Shteinhauz belong to a vast Russia-based network of fake TikTok accounts posing as real users from Germany, France, Poland, Israel and Ukraine.

Using a combination of hashtag searches and TikTok's own recommendations, BBC Verify was able to trace hundreds of similar videos targeting dozens of Ukrainian officials.

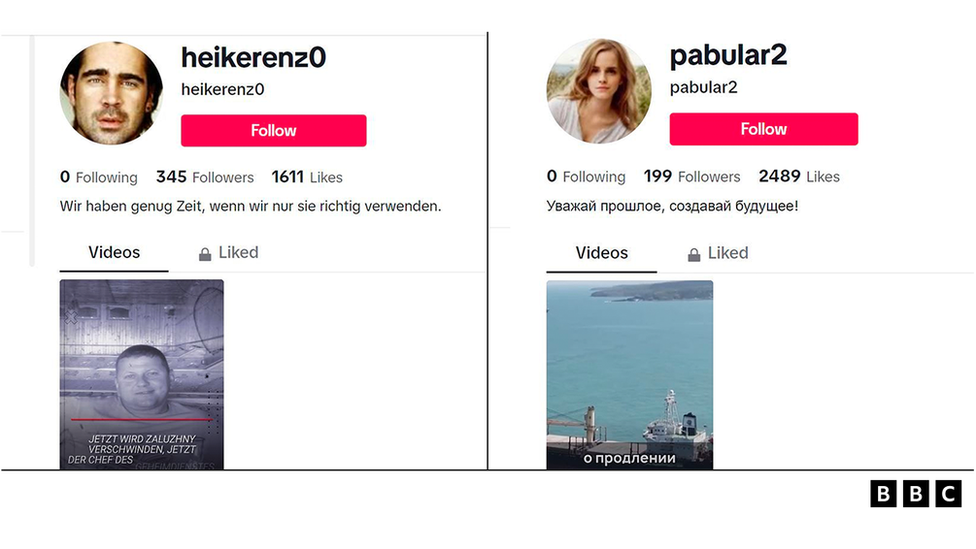

The accounts that posted them used stolen profile pictures, including those of celebrities like Scarlett Johansson, Emma Watson and Colin Farrell.

With only a handful of exceptions, they posted just one video each - a tactic TikTok says is new and aimed at evading detection and manipulating the platform's system for recommending videos to users.

Some TikTok accounts that were part of the network used stolen images of celebrities, like Colin Farrell and Emma Watson, in their profiles

The effort appeared to have been co-ordinated: sometimes videos were released by different accounts on the same day and featured identical, or very similar scripts.

During the investigation, BBC Verify found consistent, circumstantial evidence pointing to a possible Russian origin of the network.

This included linguistic mistakes typical of Russian speakers, including some Russian phrases that are not used in other languages. Also, many of the videos contained links to a website previously exposed by Meta as part of a Russian-linked network impersonating legitimate Western news websites.

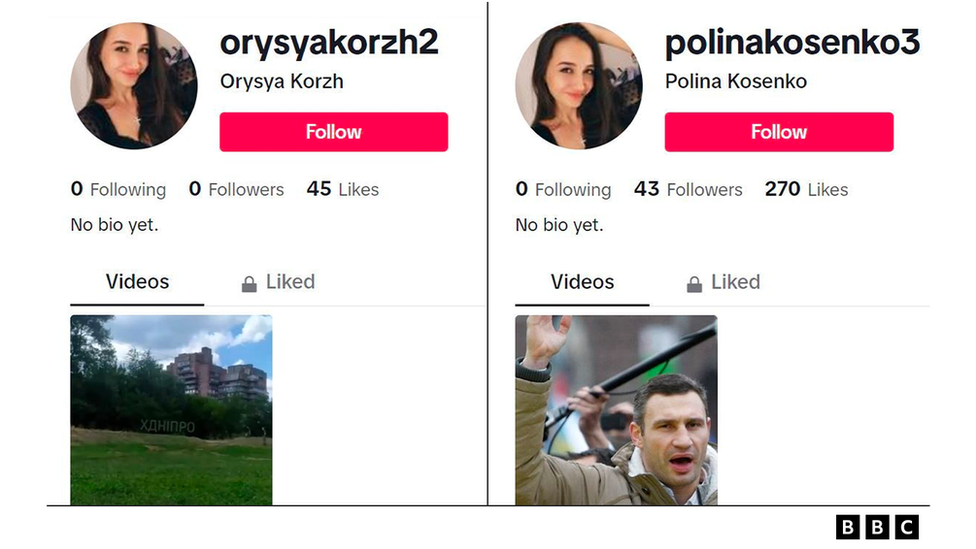

Some of the fake TikTok accounts identified by the BBC used the same stolen profile picture with different names

Many of the videos analysed by BBC Verify targeted Mr Reznikov, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and other Ukrainian officials, portraying them as obsessed with money and uncaring about ordinary Ukrainians or the war effort.

They avoided direct allegations of wrongdoing, but implied politicians had bought luxury property or goods during a time of war - claims that, when checked, always turned out to be false.

Ms Shteinhauz believes this steady drip of innuendo played a role in her father's dismissal: "It affected the life of my dad and his career."

Previously praised as a key figure in Ukraine's efforts to lobby Western countries for arms supplies, Mr Reznikov was sacked from his job as defence minister in September.

One video on its own may not have had any effect, Ms Shteinhauz said, but "when it goes like five times from different parts of the world and from inside the country, it starts to work".

Mr Reznikov lost his job amid an anti-corruption drive and a number of scandals at the defence ministry involving the procurement of goods and equipment for the army at inflated prices. However, he was not personally accused of corruption.

Announcing the decision to replace Mr Reznikov, President Zelensky said "the ministry needs new approaches". Although he made no mention of corruption in his statement, some in Ukraine welcomed the resignation that followed multiple accusations of corruption which involved Mr Reznikov's subordinates.

Roman Osadchuk from the Atlantic Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab, who investigated the network in collaboration with the BBC, external, said that the fake accounts targeting Ukrainians were trying to undermine their trust in the country's leadership.

"They're trying to make Ukraine less resilient in a way and [make] Ukrainian society stop fighting the Russians," he said.

Renee DiResta, technical research manager at Stanford Internet Observatory, says the videos' focus on corruption in Ukraine's war effort was particularly aimed at the West.

"All of these different things they're alleging [about Ukrainian officials] as the forms in which the corruption becomes grift, it would be to undermine continued support, particularly by European countries for the Ukrainian war effort."

WATCH: Three clues to Russia's propaganda network on TikTok

More accounts found

When we reported our findings to TikTok, a spokesperson said: "We constantly and relentlessly pursue those that seek to influence our community through deceptive behaviours, and we have removed a covert influence operation originating from Russia, as part of an investigation initiated by TikTok and to which the BBC has contributed."

TikTok said it was still investigating who was behind the network and had found fake videos in two additional languages - Italian and English.

Despite TikTok's efforts to shut down the network, in the weeks since BBC Verify reported the accounts, the app has recommended us dozens more videos that appear to be part of the same network.

Some of them were posted as recently as late November and covered recent events.

Graphics: Katherine Gaynor