The mountain wilderness where British teen Alex Batty lived for years

- Published

Nestled in the foothills of the Pyrenees, with the River Aude flowing gently through, Quillan could lay claim to one of the most picturesque scenes in all of France.

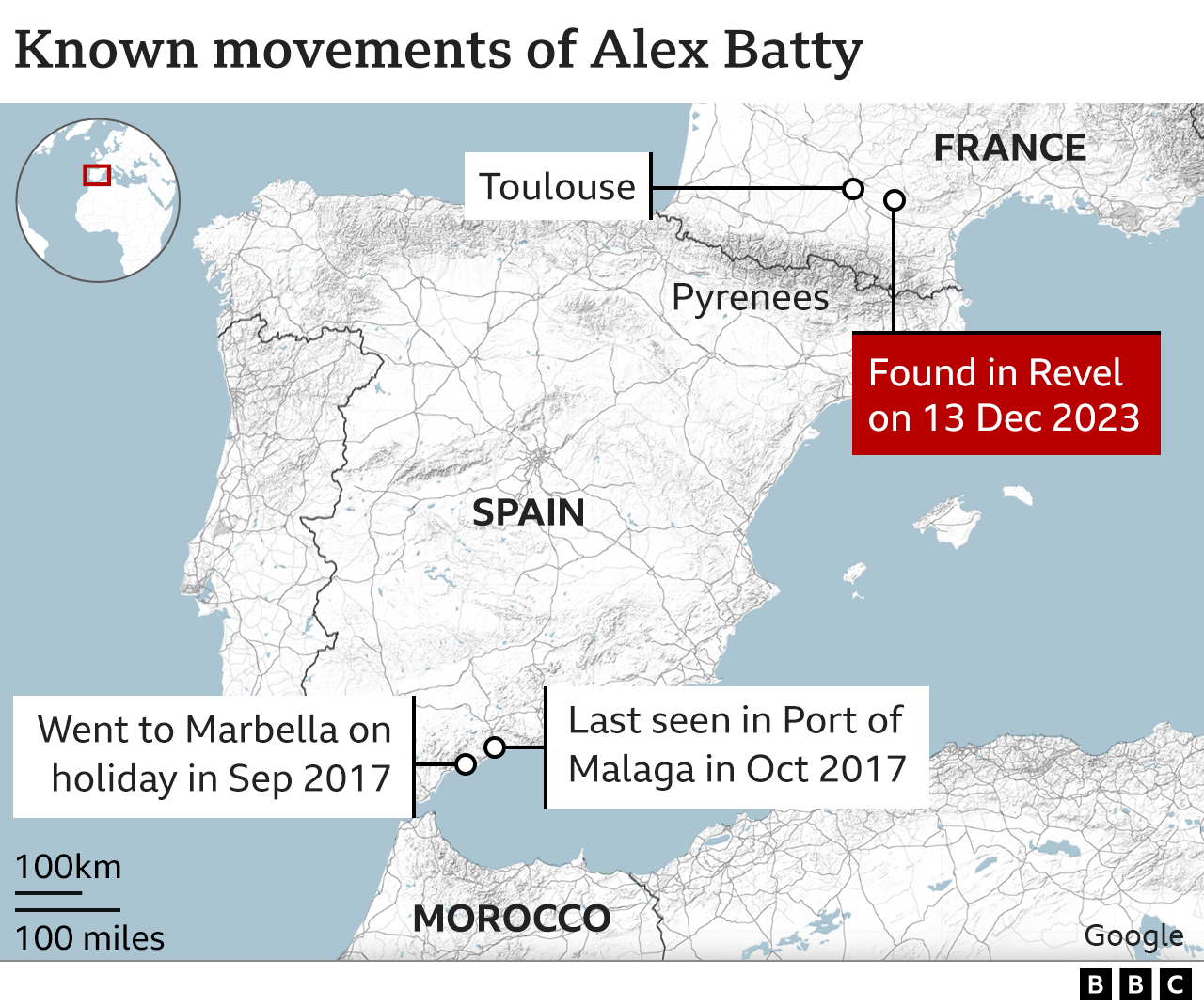

It was here that British 17-year-old Alex Batty, missing since going on holiday with his mother and grandfather in 2017, reportedly emerged this week from the mountain mist after six years in the wilderness.

By the time he had stumbled upon the narrow streets of Quillan he had been walking for four days, according to French police.

"It was such a sad story, but at least it has a happy outcome," says pensioner Martine Vincent, who we meet walking her three-year-old dog called Rambo.

"Although I worry for him psychologically, having spent those years far from home in such a remote place."

Martine, who moved here from Marseille after retiring, is a link between two parallel universes that co-exist in this vast corridor of southern France.

The first embraces the tiny world of the church, the brasserie and the village square.

The second - all around us, but out of sight - is home to a mixture of international nomads who have opted out of what may be regarded as "normal life".

Connecting the realms, Martine sells crepes in the summer to members of the communes, who venture down from their fields and plateaux for this staple of French cuisine.

"A lot of people here think they're wrongdoers, high on drugs, but you find drugs everywhere. They just want an alternative life," she says.

The further you travel from Toulouse - the region's largest city - the weaker the phone signal and the less stable the link to the outside world.

For decades, this portal to the Pyrenees has offered a pathway to a different existence - one in which the teenager from north-west England found himself for at least two years.

Some communities in this part of France are rooted in religion, others strive for spiritual enlightenment and then there's the yoga retreats. A hodge-podge of ideals and aspirations. Utopia for some - danger in the eyes of detractors.

Quillan resident Martine Vincent says those living in communes near the town simply want an "alternative life"

"There are so many different people here," Agathe tells us as she sips a lunchtime beer outside the Healthy Life restaurant in the town of Espéraza.

The 26-year-old explains that she was studying for a psychology degree before she realised she wanted to live her subject, not study it in textbooks.

"I live about 20km from here. It's one piece of land, I'm with the forest, with the river. I have fire and eat from my garden," she says.

Agathe says Germans, Spanish and Britons come and go and she wasn't surprised that Alex lived around the area with his mother and grandfather.

"Here the nature is wild. People share everything. Everyone has a free mind. It's a choice to live as simply as possible. You can really live outside of everything," she says.

Looking on across the table and nodding slowly is Agathe's friend Julien who, like her, has been leading an itinerant life for the last six years.

He has a pet crow tethered to his large black rucksack.

Soon they will begin the journey back to resume their remote lives, devoid of shops, electricity and all that most people would deem essential.

"This is my vision of happiness but it is not for everyone," admits Agathe.

Further along the valley, the temperature is dangling above freezing but we find half a dozen nearly-naked figures huddled in a stream.

"Saint Magdalene used to bathe here," a woman tells us, as we explain from a respectful distance the story we are working on.

"Go in the water," she tells us, "and you will find the answer to all of your questions."

The woman goes by the name "Plume" or feather.

She and three others are painting stones before they venture into the natural thermal bath here at Rennes-les-Bains.

"I've travelled, and I'm still travelling," says the 32-year-old mother of one.

Julien, a member of one of the communes, seen with his pet crow

I immediately think of Alex's experience from the age of 11 to 17: having never gone to a school in this time, so say the French police.

I ask Plume about her own son.

"My child is nine and I've been home-schooling him for nine years. But this is the first year he's been at a school - because it is an alternative school," she says.

She says they follow the curriculum, but there is more.

"They also teach how to live in nature, build huts, do blacksmithing - things that society needs as we get back to basics," she says.

Rather than feel estranged from reality, Plume says her way of life is making sense to more and more people.

"I don't think there are two worlds, there's only one, but it's a world that's changing. There are things that we moved away from, but we are now coming back to them."

Back in Toulouse - France's fourth largest city, and a symbol of the modernity many Pyrenees communities have eschewed - the authorities say that Alex experienced no physical violence during his years in the mountains.

The psychological impact will take longer to assess, but there was no evidence he was living in a cult, declared the public prosecutor.

But plenty of people are concerned that many ending up in the seclusion in the mountains rapidly become brainwashed and divorced from their families - and reality.

"We have identified what we call the triple break: the break with family, social ties and with society," says Catherine Katz, who supports families whose loved ones have joined cults.

Her organisation - the National Union of Associations for the Defence of Families and Individuals (UNADFI), which works to identify and help the victims of cults - was set up nearly 50 years ago and is funded by the French state.

She fears that Alex will have already suffered from being prised from the life he knew in Oldham.

"The fact that he was not attending school here is a social break: no contact with children, teachers."

But it was his separation from his grandmother - his legal guardian - that seems to have been the split he was most keen to reconcile.

After walking away from his itinerant lifestyle of the past six years, his first message to the outside world was to her.

"Hello Grandma, it's me Alex," he wrote. "I'm in France Toulouse. I really hope that you receive this message. I love you. I want to come home."

Additional reporting by Marianne Baisnee.

- Published15 December 2023

- Published15 December 2023