KGB spy who rubbed shoulders with French elite for decades

- Published

For decades, KGB spy Philippe Grumbach rubbed shoulders with countless political figures and celebrities

Major French magazine L'Express has revealed that its prominent former editor, Philippe Grumbach, spied for the Soviet Union for 35 years.

Grumbach was an exceptionally well plugged-in figure in French society for decades.

He counted presidents, actors and literary giants as close friends. He was a legendary figure in journalism who shaped the editorial direction of one of France's most successful publications. When he died in 2003, Minister of Culture Jean-Jacques Aillagon said Grumbach had been "one of the most memorable and respected figures in French media".

But he was also "Brok", a spy for Russia's KGB intelligence agency.

Extensive proof of Grumbach's duplicitous life can be found in the so-called Mitrokhin archives - named after the Soviet major who smuggled thousands of pages of documents out of Soviet archives and handed them to Britain in 1992. They were later compiled into a book by Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin himself.

Among the thousands of pages of documents are profiles outlining the characteristics of Westerners who spied for the Soviet Union.

Several months ago, a friend of Etienne Girard, the social affairs editor at L'Express and the co-author of the Grumbach exposé, informed him that an acquaintance who was researching the Mitrokhin files had come across mentions of L'Express. The documents said that an agent with the code-name of Brok worked for the KGB - and spelled out biographical details that matched Grumbach's.

Mr Girard's interest was piqued immediately.

"I started to dig into it and found Grumbach's name written in Russian, and some photos," Mr Girard told the BBC. "And then things got much more serious. I got in touch with the French secret service to confirm that Brok was indeed Grumbach - and things snowballed from there."

Born in Paris in 1924 into a Jewish family, Grumbach fled France with his mother and siblings in 1940 - the year Nazi Germany invaded and Marshal Philippe Pétain took power in Vichy with a collaborationist regime. Grumbach joined the US army almost immediately and fought alongside the resistance in Algeria in 1943. After the war, he joined the AFP news agency - but resigned soon after in protest at the French government's actions in the war in Indochina.

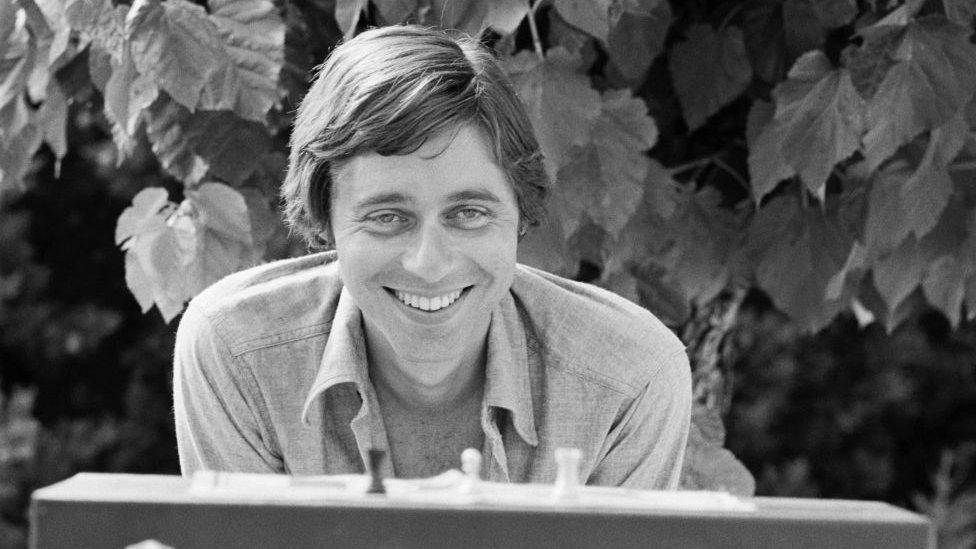

Philippe Grumbach as a young journalist

In 1954, Grumbach was hired to work at L'Express by Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber, its founder.

From then onwards, Grumbach began rubbing shoulders with some of France's most prominent figures of the 20th Century.

He helped rehabilitate the then-senator - and future president - Francois Mitterand's reputation when he was accused of staging a fake assassination in 1960. He was close to the powerful Servan-Schreiber, President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and prominent statesman Pierre Mendès France, among others. Actors Alain Delon and Isabelle Adjani were guests at his 1980 wedding, where writer Francoise Sagan and Pierre Berge, co-founder of Yves Saint Laurent, were the legal witnesses.

And Grumbach was a spy throughout.

Some may view his decision to spy for the Soviet Union as a romantic tale of loyalty to a doomed regime. But Mitrokhin himself speculated that while it was probably ideology that initially attracted Grumbach to the KGB, after only a few years his reasons for staying on as a spy had less to do with wishing to advance the cause of communism in Europe, and more with his desire to make enough money to buy a flat in Paris.

The financial incentives were certainly appealing. According to the Mitrokhin files, between 1976 and 1978 alone Grumbach was awarded the equivalent of today's €250,000 (£214,000) for his services to the KGB. On three other occasions in the 1970s, he received an extra bonus for being one of the top 13 Soviet spies in France.

Yet it is unclear what missions he carried out exactly. The Mitrokhin files show that during the 1974 presidential election the KGB gave him fabricated files which were meant to create tensions between right-wing presidential candidates. Although L'Express quotes documents as saying that Grumbach was entrusted with the mission of "settling delicate issues" and "liaising with representatives and leaders of political parties, and groups", there are few other concrete examples of Grumbach actively helping the USSR.

Maybe that is the reason why, in the early 1980s, the KGB severed ties with him. According to the Mitrokhin files book, KGB agents in Paris deemed Grumbach "insincere" and felt he exaggerated his abilities to gather information and the value of his intelligence. He was let go in 1981.

We will never know whether Grumbach was relieved that his double life was no more, or how he felt about his years of service to the KGB.

Whether because of shame or a lingering sense of loyalty, he rebuffed the only known attempt in 2000 by a journalist, Thierry Wolton, to find out more about his years as a spy. Grumbach initially appeared to obliquely admit to his past, but later rowed back, threatening to sue Wolton if he went ahead with the tell-all book he was planning.

Wolton dropped the project, but it seems the incident sparked in Grumbach a desire to talk about his experience.

His widow Nicole recently told L'Express that, soon after the Wolton visit, her late husband told her the truth. "He explained to me that he had worked for the KGB before we got married," she told the magazine. She said he mentioned having been "revolted" by the racism he witnessed in Texas while he was in the US army, and implied this led him to seek a collaboration with the USSR instead. "He immediately added that he wanted to stop almost right away, but that he had been threatened," Nicole told L'Express.

Mr Girard says he had no problem unearthing the truth about its former editor-in-chief.

"I definitely had the sense that I was doing my job. It's up to us to do the investigation, because it concerns us - even if it means unearthing uncomfortable truths," he said.

Writing the piece took three months, but it has paid off. Almost every media outlet in France has picked up the story - possibly because many still remember Grumbach as a towering figure who dominated the French media landscape for decades.

Some may be tempted to dust off their old copies of L'Express from the Grumbach years in search of subliminal pro-Soviet messaging. But they're unlikely to find anything. In the 1950s, under Grumbach's first stint as an editor-in-chief, L'Express leaned left without ever endorsing communism; in the 1970s, when Grumbach was again at the helm, L'Express moved to a resolutely moderate, liberal, centrist space.

As the report in L'Express points out, Grumbach's work as a spy was never to spread propaganda.

"He was careful to keep his work as a spy separate from his work as magazine editor," Mr Girard said. "But this is precisely why it all worked. The KGB wanted him to hold on to his cover of a centrist bourgeois to keep flying under the radar."

"It was fully in the spirit of the KGB. It was a smart move. And it worked."