German economy is in 'troubled waters' - ministry

- Published

Robert Habeck has previously warned that the economic situation in Germany was 'dramatically bad'

The German economy is in "troubled waters," according to country's economy minister.

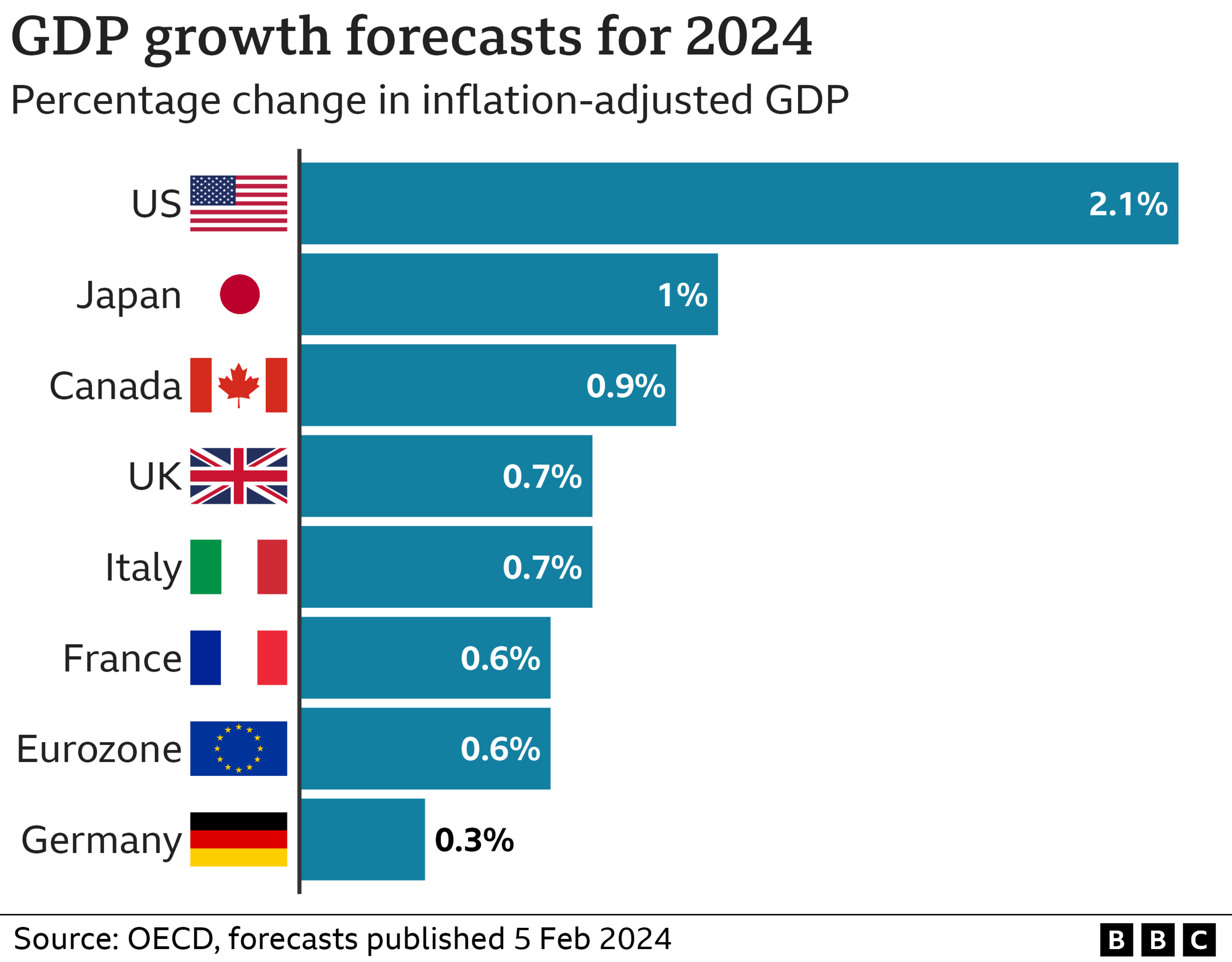

Robert Habeck said the German government's forecast for economic growth for 2024 had been revised down from 1.3% to 0.2%.

This means that Europe's largest economy has effectively stalled - although it has avoided entering a full-blown recession.

Mr Habeck previously called Germany's economic situation "dramatically bad".

Today, he said that Germany had been hit by a "very specific situation" after Putin's full invasion of Ukraine because its energy-intensive industries were dependent on Russian gas.

Germany's reliance on exports made it particularly vulnerable to changes in global trade patterns, he said, and the broader structural problem for the German economy was its lack of workers. Without migrant workers Germany's economy would collapse, Mr Habeck said.

Energy costs soared after Russia's full invasion of Ukraine two years ago. This sparked inflation, meaning that households are feeling squeezed.

The country may in fact have already slid into recession, according to a warning by Germany's central bank, the Bundesbank.

The German economy shrank marginally in 2023 and contracted by 0.3% in the fourth quarter of that year.

In its monthly report the Bundesbank said "stress factors" would probably remain and that economic output could therefore "decline again slightly in the first quarter of 2024".

Two negative quarters in a row would put Germany into a so-called technical recession.

Given that the German economy is predicted to grow slightly in 2024, economists are not talking of a full-blown recession.

Inflation rates are now falling, unemployment remains low and energy costs have come down, meaning that economists expect the economy will gradually recover this year. Despite gloomy predictions, Germany managed to successfully pivot away from Russian gas without the lights going out. After years of stagnation, wages in many sectors are rising, which should boost consumer demand.

But businesses are pessimistic.

André Kasimir owns a building firm and says the government is not helping businesses like his

Germany is on its way to being the "sick man of Europe", claims André Kasimir, who owns building firm Kasimir Bauunternehmung.

High interest rates, skilled labour shortages and the country's famed bureaucracy have, say industry figures, plunged the sector into crisis. In 2023 insolvencies in the construction sector rose more than 20%.

Bosses say building new homes has become "practically impossible", despite a desperate housing shortage in cities like Berlin.

Construction projects take far too long to get approved while Mr Kasimir also views heating and noise regulations as too costly.

"The government does not have a clue what to do to make it easier for us to build and to live," he said.

Business leaders say that many of the country's economic woes are caused by political in-fighting. Politicians are squabbling over the government's new law to stimulate the economy. Mr Habeck has drafted legislation which should cut bureaucracy and give German businesses billions of euros of tax breaks.

The law has been passed in German parliament's lower house, the Bundestag, but is being blocked by opposition conservatives in the upper house.

Squabbling within Chancellor Olaf Scholz's argumentative three-way governing coalition has also irritated voters, meaning that the government's poll ratings are at a record low. Initial plans to paper over policy differences with lavish spending were blown up when the constitutional court ruled the government's budget illegal.

Student Elmedina says she is 'not so satisfied' with what Germany has to offer right now

Government leaders have opposing views on what the solution is. Economy Minister Robert Habeck's Green Party wants to amend constitutional debt rules to allow more spending on infrastructure. The liberals, who run the finance ministry, view low debt as sacrosanct and are pushing for tough austerity measures.

The obvious divisions within the coalition are creating a lot of "uncertainty", says Professor Stefan Kooths from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

Deep unhappiness with the political class isn't hard to find on the streets of Germany's capital.

"We fell, especially under the government of Angela Merkel, a bit asleep," says Berlin resident Cathrin. "So I think we have to catch up against the big economies like China."

Architecture student Elmedina is from Kosovo but, dismayed by a lack of good job opportunities, she's questioning whether her future does now lie in Germany.

"I had an idea that I would be able to live a better life… but I'm not so satisfied with what Germany has to offer right now."

- Published4 February 2024

- Published9 January 2024