Guernsey resistance to German occupation 'not recognised'

- Published

The islands were heavily garrisoned and fortified as part of Hitler's Atlantic Wall

Sharing news today is so simple, a tweet can be seen by millions - but under the Nazi occupation of Guernsey spreading news could lead to deportation and prison.

Now 70 years on, campaigners are calling for those islanders who defied Hitler's orders in this and other ways, to be properly recognised.

German armed forces ruled the Channel Islands from June 1940 until May 1945.

They imposed a curfew, made everyone carry identity cards, banned the sale of spirits and later banned radios.

Islanders broke all the rules, but it was for continuing to listen to his radio that saw one man deported never to be seen again.

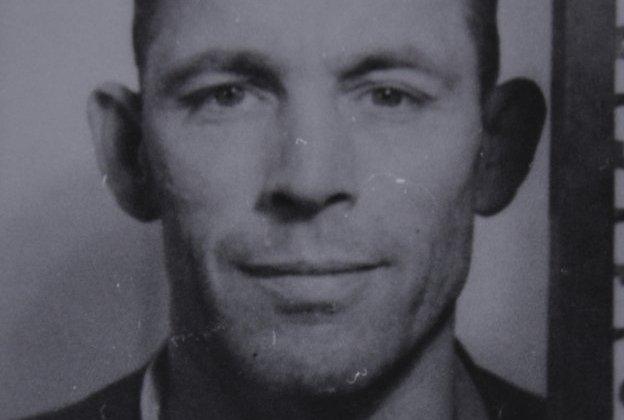

Joseph Gillingham was one of a number of islanders involved in the Guernsey Underground News Service (Guns).

It was a loose collection of people who secretly listened to the BBC News, on home-built or radios they had not handed in, wrote the news down and shared it with other islanders.

Often the news would contradict that put out through the Guernsey Evening Press and The Star, which were only allowed to carry war news provided and approved by the German authorities.

At the height of the occupation in May 1943, about 13,000 troops were on Guernsey and 3,800 on Alderney

Occupation of the Channel Islands

Only British soil to be occupied during the war

After the German offensive raced through France the British government decided the islands were not strategically important and left them undefended

This was not communicated to the Germans who bombed St Peter Port Harbour and targets in Jersey, killing 44 people

German troops landed in Guernsey by plane on 30 June 1940 - the start of five years of occupation

The islands were turned into an "impregnable fortress" on the express orders of Adolf Hitler

A fifth of all the defence works in the Atlantic Wall - a defensive line stretching from the Baltic to the Spanish Frontier - were built on the islands

The island's government continued under German rule, which some see as collaboration

Mr Gillingham was one of five Guns members who were caught, deported and imprisoned for wireless offences and secretly spreading news.

He was deported on 4 June 1944 - just two days before D-Day - and served 10 months in Naumberg prison, south of Leipzig, Germany.

On his release date on 2 February 1945, he was allowed to say goodbye to his brother-in-law Ernie Legg, but was not seen again.

Searches were unsuccessful and he was officially declared dead in 1947.

After he said goodbye to his brother-in-law in Naumberg prison Joseph Gillingham was never seen again

His family has resisted island authorities and long campaigned for a memorial for him and those like him who resisted the German occupation.

Jean Harris, who was five months old when her father Mr Gillingham was deported, said it was important they were remembered even if many of those who would have "really appreciated it" such as her mother were no longer alive.

His wife Henrietta had been a part of Guns, but her part was kept secret by her husband and brother so she and her daughter would be safe. They first pushed for a memorial to be erected in 1947.

"We've been waiting for 70 years for something to happen, but we're hoping this memorial will go up on the wall and I shall feel very proud and honoured," Mrs Harris said.

Her husband Allan is spearheading a campaign to raise about £2,000 for a pink granite memorial to be sited at the White Rock, St Peter Port, alongside other memorials related to World War Two.

The resisters who died

Sidney Ashcroft - convicted of serious theft and resistance to officials in 1942. He is thought to have died after a selection of weak prisoners were taken from Straubing prison, Germany, on 24 April 1945

Joseph Gillingham - imprisoned for recording and distributing news, last seen on 2 February 1945

John Ingrouille - found guilty of treason and espionage and sentenced to five years hard labour. He survived a hard labour prison in Brandenburg, but died in a displaced persons camp on 13 June 1945

Charles Machon - brainchild of Guns, received the longest sentence of the five and was sent to Rheinbach prison in May 1944, then four months later on to Hameln prison where he died on 26 October

Percy Miller - sentenced to 15 months for wireless offences he was sent to Frankfurt-Preungesheim in July 1943 where he was caught passing a note to a fellow prisoner and confined in a punishment cell where he died on 16 July 1944

Marie Ozanne - refused to accept the ban placed on the Salvation Army she would preach in public and was vocal in her protests about the treatment of Jews and slave labourers and became ill in prison and after her release died from peritonitis on 25 February 1943. She is the only one to be named on a plaque in the island

Louis Symes - sheltered his son 2nd Lt James Symes, who was on a commando mission to the island with 2nd Lt Herbert Nicolle. Mr Symes was sent to Cherche-Midi prison in Paris where he died in unconfirmed circumstances - just days before his sentence was revised and he would have been released

An eighth person died, but their family has asked for their details to be kept private

Tom Remfrey, chairman of the Guernsey Deportees Association, said no one who had resisted the German occupation was put forward for an award after the war.

He said many islanders were outraged at the decision, which the authorities said was because resistance was against the spirit of the Hague Convention, which along with the Geneva Convention set out laws of war and war crimes in international war.

Mr Remfrey described this as "absolute rubbish" and said Guernsey needed to follow Jersey's lead in marking the impact of the occupation.

On Holocaust Day - 27 January - the names of all those from Jersey who died as a "direct cause or result" of the occupation were read out and the event was "properly and honourably attended", he said.

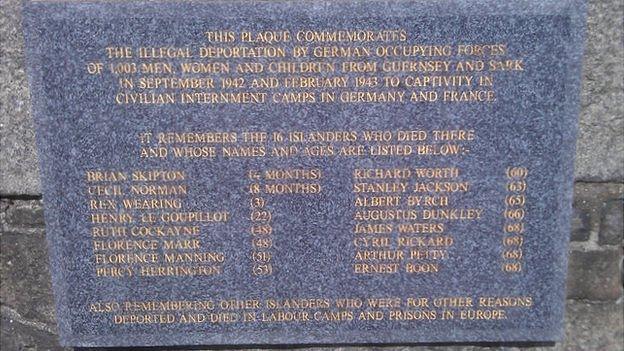

Plaques remembering evacuees, deportees and the holocaust are already in place at the White Rock

Dr Gilly Carr, from Cambridge University, who studied resistance in the islands and said it was a subject that divided Guernsey, but she felt those who had committed acts of resistance should be acknowledged as heroes of the occupation.

She said: "The authorities were very worried the Germans would have taken reprisals on the entire community so because this was a very strong line from the island's leaders [not to resist].

"[After the war] it was very hard for people to say actually the resistors did the right thing.

"They were disobeying orders and some people thought they really could have got everyone else into a lot of trouble.

"[But] it's important to acknowledge those who did resist as many of them suffered in German concentration camps and Nazi prisons on the continent."

The deportation of more than 1,000 islanders was done on the direct order of Adolf Hitler

Most deportees are already remembered on a plaque near to the proposed site of the memorial, commemorating the 1,003 men, women and children deported from Guernsey and Sark during 1942 and 1943.

These deportations were ordered personally by Adolf Hitler in response to the British internment of Germans living in the then Persia, now Iran.

Those sent first were English-born men and dependents followed by those who served as officers in World War One with the majority taken to civilian internment camps in Germany and France.

- Published20 August 2013

- Published11 May 2014

- Published25 February 2014

- Published16 March 2013

- Published21 December 2012

- Published20 September 2012

- Published18 November 2010