Should Alderney make its wartime camps tourist attractions?

- Published

Four major camps operated in Alderney between 1942 and 1944, named after the German North Sea Islands Helgoland, Borkum, Norderney, and Sylt

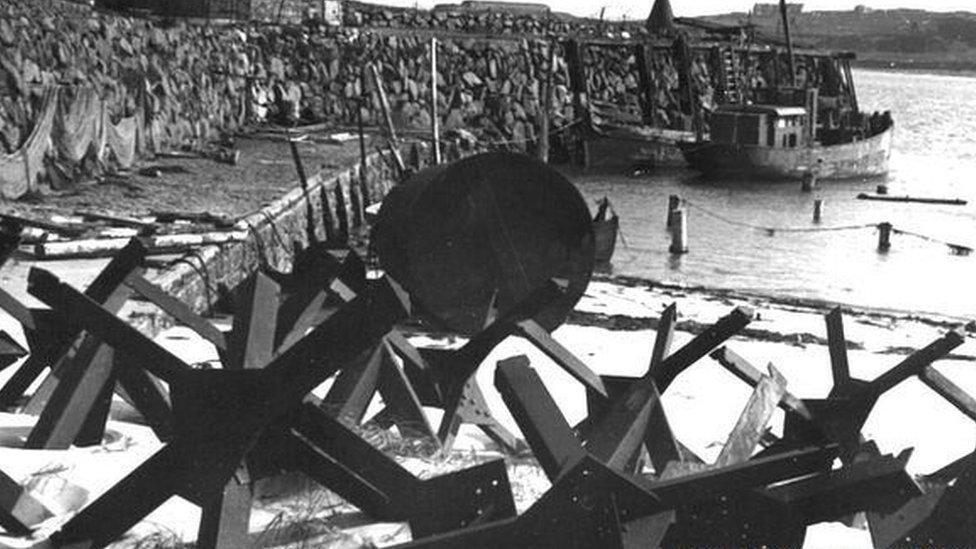

The western-most concentration camp in the Third Reich, Lager Sylt, was located on British soil - only about 70 miles south of Bournemouth on the island of Alderney. Should this camp and other relics of the Channel Islands' occupation by Nazi Germany be developed into tourist attractions?

Arrive in Alderney at its small and ageing airport and you will see an island map, pointing out Victorian forts, a Roman nunnery and World War Two coastal defences.

There is, however, no mention of the four wartime camps that housed thousands of slave labourers, many of whom died as part of Nazi Germany's attempts to turn Alderney into a fortress island.

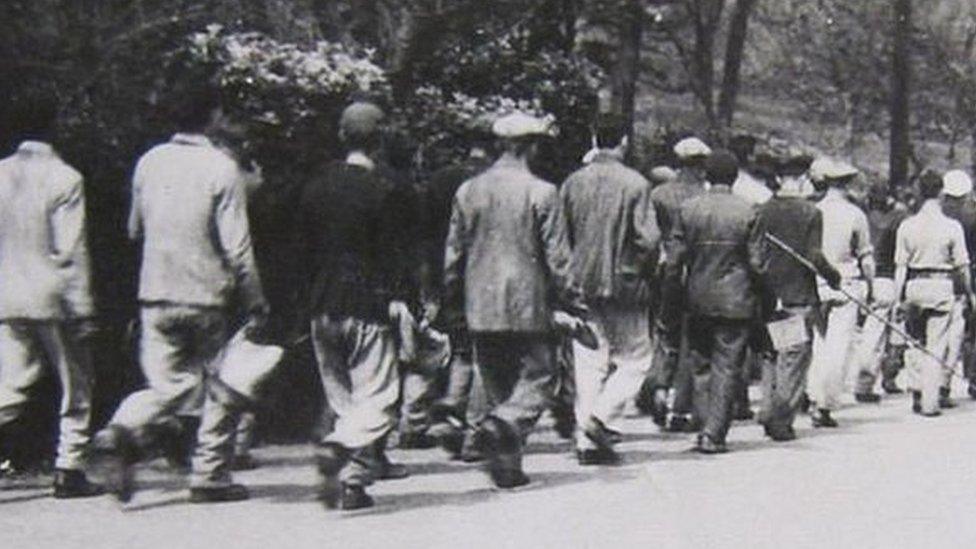

Workers were kept in conditions of "deliberate inhumanity" with beatings, disease, and starvation rife, according to a post-war report

It is these locations that Marcus Roberts, director of the National Anglo-Jewish Heritage Trail, believes should be developed as "sites of memory", in part to boost the island's flagging tourism industry.

"Alderney is perhaps the best place to go to understand the realities of the Nazi slave labour system," he said.

"People could go and understand what the consequences of tyranny are and the mistreatment of other people.

"I think there's a role for respectable tourism, which would be part of the overall tourism strategy for the island."

Alderney occupation

V1 rockets were developed in nearby Cherbourg

Demilitarised in 1940, along with other Channel Islands

Occupied by German forces in July 1940

The most heavily fortified Channel Island as part of Hitler's Atlantic Wall

Nearly all of Alderney's population was evacuated to England

Four labour camps were established - named after the German islands Borkum, Helgoland, Norderney and Sylt

Mr Roberts believes there were significantly more forced labourers on Alderney than post-war reports stated, including about 10,000 predominantly French Jews.

Albert Eblagon survived Norderney and described to Israeli journalist Solomon Steckoll in an account published in 1982 how fellow prisoners were beaten and starved to death.

Some aged over 70, they worked up to 14 hours each day building the island's fortifications.

"Every day there were beatings, and people's bones were broken, their arms or their legs," he recalled.

"People died from overwork. We were starved and worked to death; so many died from total exhaustion."

The number of his fellow prisoners and forced labourers who did not survive has been contested, ranging from an official post-war report that stated 389 deaths, to as many as 70,000.

Marcus Roberts says his research has shown a greater number of Jews were killed on occupied Alderney than has been previously estimated

Focusing on this traumatic past led to Mr Roberts being accused of promoting Alderney as a "bone-yard" and making it less attractive to visitors.

In response, he wrote a letter to the Alderney Journal, external in June defending his research and pointing to nearby northern France where military cemeteries are popular tourist attractions.

The number of people travelling to and from the island by air has fallen by more than a quarter in the 10 years to 2016, although there was a slight rise in summer 2017 compared to the year before.

But developing the island's former Nazi sites for visitors is something States of Alderney Vice President Ian Tugby is against.

"We're supposed to be a lovely island, going forward," he said.

"I'm more interested in the future, basically, than what's gone on in the past, because the past is gone.

"We can't change it, and do we want to continue to drag up the downside of what went on in Alderney all those years ago?"

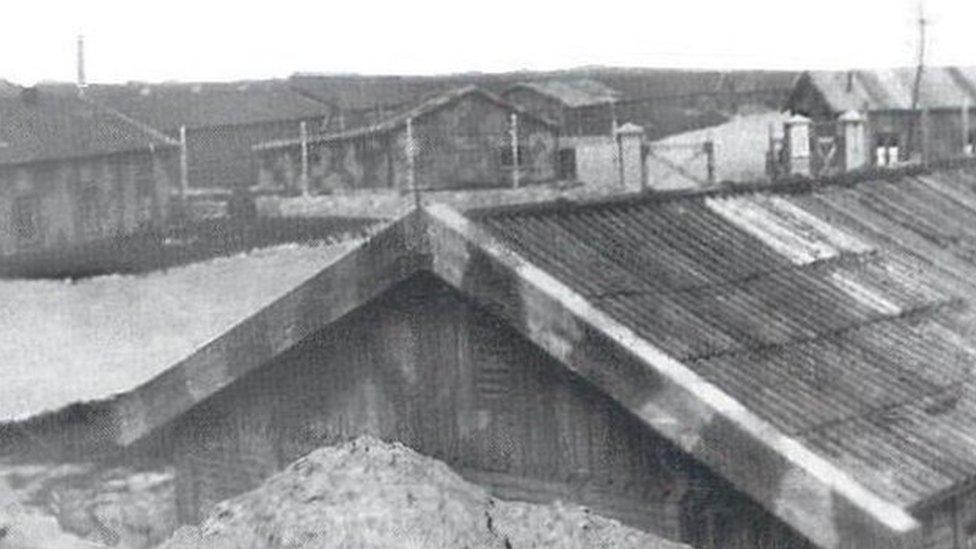

The entrance posts of Lager Sylt, the western-most concentration camp in the Third Reich

Alderney's camps

The four major camps were run by the Todt Organisation, responsible for Nazi Germany's military and civic engineering.

Sylt, the only concentration camp, was taken over by the SS Baubrigade in 1943, part of the so-called death's head formation, which ran concentration camps.

More than 40,000 camps and incarceration sites were established by the Nazis across Europe for forced labour, detention - and mass murder.

Alderney inmates were predominantly Russian, and comprised of prisoners of war, forced labourers, "volunteers" from Germany and occupied countries, Jews, and political prisoners.

Helgoland and Norderney, today a campsite, both had the capacity for 1,500 forced labourers.

Borkum housed specialist craftsmen, many ordered there from either Germany or occupied countries, with between 500 and 1,000 prisoners at the site.

Mr Tugby's voting record in the island's parliament suggests he is serious.

In 2015, he and fellow Alderney-born politician Louis Jean were the only two politicians to vote against designating Lager Sylt a conservation area.

Economic independence for the island, reliant on its larger neighbour Guernsey, lies in approving a £500m electricity cable project linking France and Britain through the island, not in promoting its wartime occupation, Mr Tugby said.

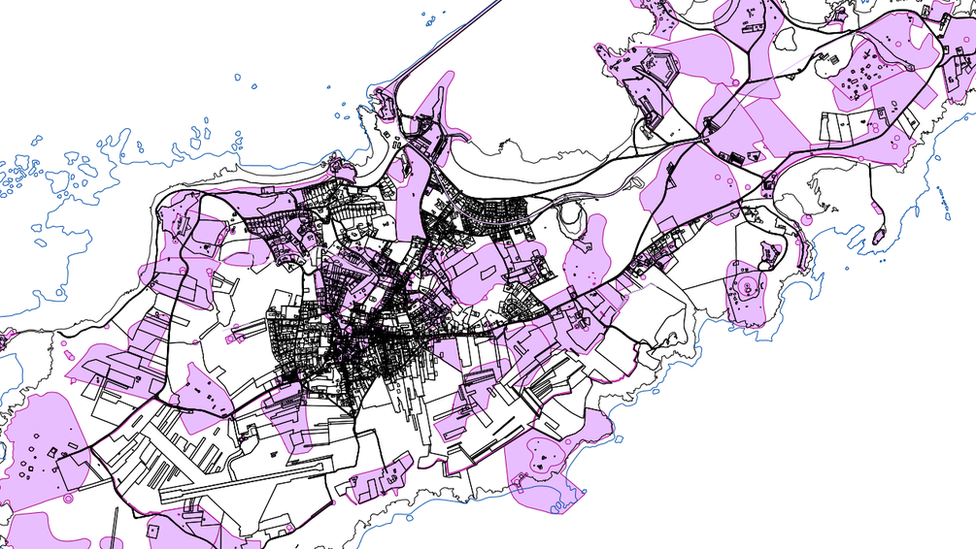

The FAB Link project will run through a conservation area, at Longis Common, but developers say the cable would avoid known World War Two burial sites

Graham McKinley voted in favour of Lager Sylt becoming a conservation site, and would like the dark past of the three other island forced labour camps to be made more apparent to visitors

However, fellow politician Graham McKinley, who voted in favour of Sylt being protected, would like to see a similar memorial to the one at Sylt (pictured above) at the three other forced labour sites, including Lager Norderney, the largest, which is today home to Alderney's campsite.

"There should be some sort of memorial put up there, and some sort of indication that that was happening."

People would visit sites like these, he said, if they were more aware of the island's "unique wartime interest".

"Look at the prisoner-of-war camps in Poland and in Germany which attract an enormous amount of visitors every year and bring in much-needed revenue," he said.

"We need that sort of thing."

Alderney's population was evacuated ahead of its occupation, with few local eyewitnesses to what happened in the island's camps

Unlike with the island's plentiful occupation-era coastal defences, there is little remaining of the forced labour sites, except for entrance gates and the odd structure.

Sylt is protected after Alderney's government designated it a conservation area in 2015, while the other three sites could yet be afforded similar protection under a plan awaiting government approval.

The 2017 Land Use Plan would see the sites where the forced labour camps stood, and other locations of wartime significance, registered as heritage assets.

Only development that is "sensitive to the former use and history of these assets" would be permitted at the wartime sites, under the plan.

Various parts of Alderney, highlighted in purple, have been identified as "unregistered heritage assets of significant value"

Such protection is long overdue, according to Trevor Davenport, author of Festung Alderney, a book on German defences on the island.

Despite a long association with protecting World War Two sites, Mr Davenport does not, however, want to see former forced labour sites developed for visitors.

"I have no objection to people being made aware of the labour camps," he said.

"But it is not, unless you are a ghoul, a heritage issue that needs promoting, except as part of the overall occupation story."

The Alderney Museum in St Anne is home to a small section telling the story of the island's forced workers

Certainly, the island's tourism body Visit Alderney is reluctant to promote this part of the island's history above any other.

"Our tourism focus remains on the historical importance and education of all our heritage periods," a spokeswoman said.

"The local population are respectful of our past whatever the historical period.

"Promoting tourism and respectful memoriam should not be confused."

Former forced labour camp Norderney is today home to Alderney's campsite

The Hammond Memorial overlooking Longis Common contains tributes in many languages to those who died constructing this small section of Hitler's Atlantic Wall

But for Marcus Roberts, encouraging people to come to Alderney to consider what happened there during the Nazi occupation makes sense both financially and morally.

Not only was this important for the descendents of Nazi Germany's victims, he said, but also for the historical record.

"It's not just an island matter; it does affect people literally from around the world.

"Each person who died was someone's family, someone's son, and all lives are valuable."

- Published9 May 2017

- Published29 November 2016

- Published31 March 2016

- Published10 March 2015

- Published15 December 2010