Can MPs force laws on the Crown dependencies?

- Published

- comments

Guernsey Chief Minister Gavin St Pier has written open letters to national newspapers arguing against the MPs' move

Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man are not represented in the UK's House of Commons, yet its MPs are being asked to change laws in the islands.

Some have warned the move could spark a constitutional crisis, and even calls for independence. So can MPs actually force the laws - making company ownership information public - on the Crown dependencies?

Ask Guernsey's chief minister and the answer is emphatically "no".

Gavin St Pier has led efforts to convince MPs not to back an amendment to the Financial Services Bill, forcing greater transparency on the islands' financial services sectors.

"We have no ambiguity in our view that the UK - that the Westminster Parliament - cannot legislate for us on domestic matters without our consent," Deputy St Pier says.

The move by Tory MP Andrew Mitchell and Labour's Margaret Hodge has been backed by more than 80 MPs, including 24 Conservatives.

The pair have already succeeded in getting Britain's overseas territories such as Bermuda, Anguilla and the Cayman Islands to establish public registers of ultimate business owners.

Now, they have gathered cross-party support in calling for the UK's tax havens closer to home to follow suit - demanding Jersey, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man also have registers in place by the end of 2020.

They argue greater transparency over company ownership is an important tool in tackling money laundering, tax avoidance and tax evasion.

Dame Margaret Hodge (left) and Andrew Mitchell (right) are behind the transparency push

MPs are yet to vote on their amendment, after the government pulled the debate and votes on the Financial Services Bill - underlining the weakness of its position in the Commons.

Since then the campaigning MPs have set out their argument for forcing the law change in a strongly-worded letter to island ministers. , external

In it, they cite a 1973 report which suggested Parliament could intervene to ensure good government in the islands.

The MPs also suggested money laundering in the islands threatened Britain's national security and therefore the UK was compelled to act.

Crown dependencies' history

The Channel Islands were part of the Duchy of Normandy, so when its leader William conquered England in 1066 Jersey and Guernsey were technically on the winning side at the Battle of Hastings.

In 1204, when King John lost Normandy to the French, the islands decided to remain loyal to the English Crown, and in return were allowed to continue to be governed by their own laws.

That agreement has been affirmed in the centuries since, with both Jersey and Guernsey developing their own democratically-elected parliaments, but with their laws effectively rubberstamped by the Queen, as head of state.

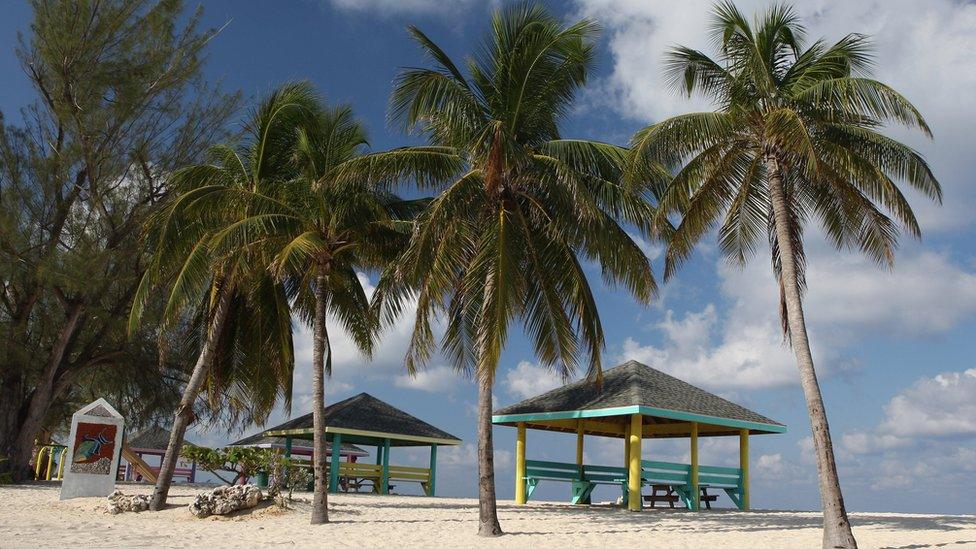

Guernsey's economy is heavily reliant on its financial services sector

The islands therefore have a different relationship with the UK to its former colonies and overseas territories, such as Gibraltar.

The Isle of Man's parliament, the Tynwald, is one of the oldest parliaments in the world. It too was granted full autonomy, and since 1866 has steadily advanced to full democracy.

The dependencies are not directly represented by MPs, but the British government is responsible for the defence and international relations of the islands.

It is the Crown, however, acting through the Privy Council, that is ultimately responsible for good government., external

The argument for intervention

Despite the islands' history of autonomy, Jolyon Maugham QC, a barrister who has advised both the Labour Party and Conservative government, says the UK does have the right to intervene.

"If you approach it as a lawyer, I don't think there is any real doubt that the United Kingdom can, if it wants to, legislate for the Crown dependencies without their consent," he says.

Mr Maugham describes the relationship as one shaped by parliament, citing the recent Supreme Court ruling on Article 50, which said there was no legally-binding obligation on London to consult the devolved administrations before passing laws which affect them.

"What the Supreme Court said was 'well there might be a convention, but it's not something we can control. If government decides it wants to ignore the convention, it can ignore the convention'. And that is undoubtedly true," he says.

Mr Maugham also sits on the advisory board of Tax Justice UK, and believes tax havens damage the functioning of what he describes as "proper" countries - economies not dependent on undermining the tax bases of others.

The campaigning MPs' transparency efforts should not come as a surprise to the island governments, he adds, pointing to efforts led by former Prime Minister David Cameron to introduce public registers in 2015.

The argument against intervention

The argument for intervening by MPs hinges, in part, on the 1973 Kilbrandon report which states the UK can only legislate without consent to ensure good government.

The low-tax dependencies argue their systems for combating money laundering do represent good government,, external despite accusations of not doing enough to combat financial crime.

Such an intervention by MPs citing Kilbrandon would be "controversial" and open to challenge, Guernsey lawyer Gordon Dawes says.

"It seems to me that we are well within the scope of what a responsible, autonomous government can and should do, in terms of keeping track of beneficial ownership of companies, and making that information available to other agencies.

"To me that is unarguable," Mr Dawes adds.

Others have also argued the relationship between the islands and the UK has evolved in the 40 years since Kilbrandon was published, , externalwhile Guernsey's government has pointed to a 2008 agreement it signed with the UK government.

It recognised the island's interests may differ from the UK's and would be a relationship of "support not interference"., external

Speaker John Bercow said the amendment would have to come back to Parliament

What happens next?

MPs will debate the Hodge-Mitchell amendment when a piece of Brexit-related legislation, the Financial Services Bill, returns to parliament.

Despite accusations of constitutional meddling, Speaker John Bercow told MPs the amendment was "perfectly proper" and would be debated and voted on by parliament.

And with cross-party support, including 24 Conservatives, it is likely the government will be defeated on the matter.

The amended bill calls for a draft Order in Council - requiring the government of any British overseas territory and Crown dependency to implement public registers by the end of 2020.

That will not be the end of the story, however.

The Queen is the head of state of each of the Crown dependencies

Such an order would have to go through the Privy Council, something lawyer Gordon Dawes says could be challenged.

"Even it cleared the hurdles in London - of a challenge there - there's a question of whether it would be respected and enforced in the islands.

"So, there's a lot of hurdles for any such legislation to clear. And obviously the hope is that we don't find ourselves in that position," he adds.

The order would have to be registered in the islands' respective courts - something Guernsey's chief minister said would be ineffective, forcing an "unhelpful" shift in the relationship with the UK.

The island has taken steps to resist such a move, with politicians approving an emergency measure giving them the final say on whether UK laws are registered locally,, external similar to a procedure already in place in Jersey.

Such is the seriousness of the situation, some have suggested the islands could petition the Queen, external, as head of State, to intervene, or seek independence, something Mr Dawes said remained a possibility.

"In principle it's possible to have a look at independence - and I can see the value of it as a political statement in the present context.

"And yes, as a matter of law it is possible. I don't think there's any great desire for it, but it remains a possibility," he adds.

- Published4 March 2019

- Published2 March 2019

- Published1 May 2018

- Published20 December 2018