Rewriting the ancient history of Stonehenge

- Published

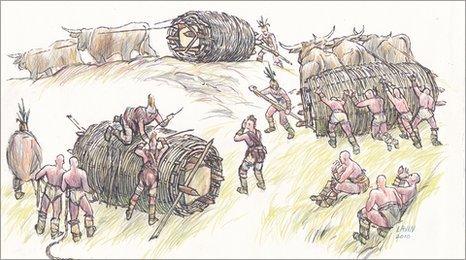

Drawing by Garry Lavin who believes Stonehenge was built by rolling stones within giant wicker constructions

Island-based designer and engineer Garry Lavin has set out to revolutionise ideas on how the ancient monument of Stonehenge was built.

The current accepted theory is that each three-quarter tonne stone was rolled for more than 200 miles on logs, but Mr Lavin disagrees.

He thinks the historic monument could have been built using wicker basket constructions to roll the boulders all the way from Wales.

"I constructed a 0.5-metre diameter structure in hazel and willow into which I placed a sharply rectangular 40kg stone from a collapsed dry stone wall," he said.

Summer Solstice

Garry Lavin (right) sets out to prove his theories with the help of a few friends

"I packed the gaps inside with reeds and rolled it down a hillside. The stone fell out at the bottom but my construction was still intact.

"The project was then taken to the edge of the local canal and pushed in and it floated with about an eighth of the mass protruding above the water, but easily towable along the canal."

So could this really have been the way our ancient ancestors chose to achieve such an incredible feat of engineering as Stonehenge?

Mr Lavin says woven structures were used widely at the time so it makes sense to assume they could also have been used in this way.

In past experiments Mr Lavin succeeded in moving a large one-ton stone in a wicker cage that he had made himself.

This year he will try to move a five-ton stone during the Summer Solstice at a time when the eyes of the world are firmly fixed on the Stonehenge monument.

Mr Lavin showed that wicker cages containing stones were able to float

"I have no doubt a four-fifths of a tonne stone could be moved great distances by surprisingly few people. The method of pulling rope like a giant bobbin creates leverage that puts the process streets ahead of other theories."

"I look forward to getting an opportunity to float our bluestone replica down a river and maybe across the Severn estuary. We've done the maths to determine the ratio of wood to stone needed to suspend it in water."

Mr Lavin hopes the project will expand people's understanding of those who lived in Britain over 5,000 years ago. He says he wants to "put some flesh on a society whose achievements rival or maybe even surpass those of the very familiar Romans in Britain".

This intriguing story has now been reported on many websites around the world and has been translated into numerous languages- so it is possible Mr Lavin will have an international audience as he attempts to revolutionise established thought on the building of one of England's most famous heritage sites.