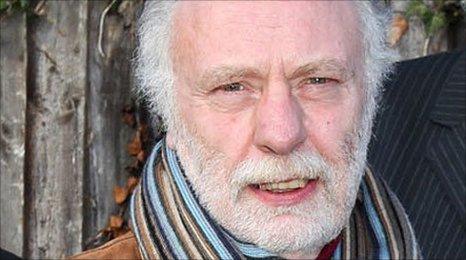

Brian Keenan on spirituality, faith, writing and fear

- Published

If life experience can enhance a writer's work, Brian Keenan has no shortage of material to draw upon.

In 1986 he was kidnapped in Beirut and spent four and a half years in a cell at the hands of Islamic Jihad.

Keenan was initially isolated for two months before being moved to a shared cell with journalist, John McCarthy.

Although anxious to avoid becoming an authority on anything, Keenan's insight into loneliness and aloneness is inevitably more profound than most.

"There's a marked difference between aloneness and loneliness. I quite enjoy solitude but loneliness is different. We all need somebody to talk to, explain things to. If we don't have that we don't have validation and life lacks meaning.

Aloneness and liberation

"Having said that I think everybody has a place inside themselves that you alone can go to. You know how to get there because you've got a key. When you go there it can be deeply enriching- it can also be a bit disturbing because it forces you to look at yourself. That's what aloneness is to me.

"It's about taking the time to look at what you are and make good what you are. Sometimes you need to put a sticking plaster on here and there. Aloneness, when you can deal with it, is about liberation."

It is this inner church where Brian Keenan goes for spiritual reflection. The more conventional methods of worship held no attraction for him before his kidnapping and they hold no attraction now.

Brian Keenan talks to the press after his release in August 1990

"I can't find anything nourishing in churches great or small. I find religion is all about control not liberation. I go to church quite a lot because I am impressed by the buildings and what they are supposed to represent, but it is only in empty desolate spaces that I find whatever is luminous; whatever is holy, whatever this 'other' thing is.

A question of faith

"In desolate empty spaces you can find an invisible portal which you can pass into. In a way this allows you to pass into yourself and look into yourself. That to me is a religious experience. This has nothing to do with all the riches of the church.

Despite rejecting conventional religion, Keenan comes across as a deeply spiritual person. He is a man who has asked himself questions of faith and emerged with his own answers.

"If there is a God out there, it better be real and it better be meaningful. It better do things which engage me in a way which I can feel and sense, otherwise it's a just a sham. But here's the paradox. I'm not religious but when I was locked up I prayed. I prayed daily and said to God that if he got me out of there I would do all sorts of things. But you can't make deals with God.

Happier times. Brian Keenan marries Audrey Doyle in Ireland in 1993. The couple now have 2 sons

"When you enter the power house of prayer you had better be wearing an asbestos suit because you are going to get roasted. I believe in prayer but you really have to know what you are doing because things will happen and then you have to deal with them."

In August 1990 Keenan's prayers were answered and he was released. After spending time recovering from his ordeal, he went on to write 'An Evil Cradling', an account of his captivity in Beirut. The book was described by the Observer as being 'Scriptural in its resonances, while being as gripping as an airport thriller'. But Keenan refuses to take full credit. He believes that a good book writes itself.

Creativity in emptiness

"I think stories are given to you and it's about writing the story in a way which transfers to somebody else. Because it's not mine, I'm just a vehicle or a tool or a pen. With 'An Evil Cradling' I drove around for weeks and weeks and weeks thinking how am I going to write this? There was a long time when nothing happened and everything happened.

"I drove to an empty beach, an ancient graveyard and a beautiful hilltop looking out over the sea. I sat for ages writing metaphors and other stuff, thoughts on eternity, emptiness and death- anything that came into my head.

"And then I went home, tore all the pages out, laid them out on the bed and switched the tape recorder on. I didn't look at the notes once but it all just came pouring out.

"The next morning I listened back to the tapes and I sat there, in my cottage with the tears rolling down my face because that was me back in Lebanon talking to me now".

Brian Keenan and Audrey Doyle with Anna and John McCarthy at the Irish Film and Television Awards

The man who was locked up in a cell in Beirut is a very different one we meet today. Brian Keenan is no stranger to self reflection and not only has he managed the unfathomable task of forgiving his captors, he has also resolved much within himself.

"When I was locked up I was afraid of being afraid, and that made me do some stupid things. I was very cocky and very stupid- that's what I am afraid of now. I used to think about my kidnappers, 'I know you have a gun but I don't care, I'm still not going to let you push me around' but that only sustains you for a while because it exhausts all your real reserves.

"There is a difference between being fearful and confronting things for no reason except the sake of your own ego. I don't do that anymore and I don't get into confrontational situations. I stay away from that nonsense now.

"It's healthy to be afraid of things, especially when you have been kidnapped. You are afraid of things for a reason and you should be. Now I think long and hard about putting myself into situations which could be fearful. I'm still afraid of a lot of things like everybody else is. I'm afraid of heights, afraid of flying and I can't swim!"

Brian Keenan's new book "I'll Tell Me Ma" is published by Jonathan Cape.