Colombia sees crime rise in major cities

- Published

Troops use motorbikes to access some of Medellin's narrow streets

When Juan Manuel Santos takes office on 7 August as Colombia's new president, one of his biggest challenges will be urban crime.

After six years of falling violence, 2009 saw the murder rate rise by 12%, the increase mainly in cities and, above all, in Medellin.

The number of murders in the city almost doubled to 1,432 in 2009 - in a city of just more than two million - and this year has seen a similar trend.

The rise in crime can in part be ascribed to the government's success in demobilising more than 30,000 right-wing paramilitaries and dismantling many drug-exporting syndicates.

This has resulted in former paramilitaries setting up new, smaller drug cartels.

They do not have the same international reach as former gangs like the cartel that took its name from the city and became synonymous with violence during the days of Pablo Escobar in the 1980s and early 1990s.

So with a glut of cocaine in the country and fewer big gangs to export the drug, there has been an increase in domestic consumption.

"What has happened is that the cartels and criminal groups are creating an internal market for drug consumption and have provoked a war for control of this new income, along with that from prostitution and extortion," said Ariel Avila, a researcher with the Bogota think tank Corporacion Nuevo Arco Iris.

Network

Nowhere is this clearer than in Medellin, where authorities believe the monthly income from drugs, extortion and money-laundering is around US$20m (£13m) a month.

The latest wave of problems began in 2008, when Pablo Escobar's heir, Diego Murillo, who also went by the alias Don Berna, was extradited to the US to face drug-trafficking charges.

For more than a decade he had run the Medellin underworld through an organisation known as the "Office of Envigado".

This was a network that imposed discipline, ran extortion rackets, money-laundering and drug-trafficking, and controlled the gangs that dominate the poorer neighbourhoods of this city, once regarded as the most dangerous in the world.

Now there is a struggle for control of the "Office" between two subalterns of Don Berna: Maximiliano Bonilla, alias Valenciano, and Erick Vargas, alias Sebastian.

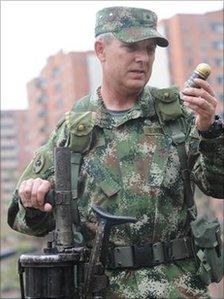

Gen Alberto Mejia's troops are supporting the police

The US has offered a $5m reward for information leading to Valenciano's arrest.

He reportedly controls 1,650 gang members in Medellin, while Sebastian is said to command more than 2,000 followers.

The latest big battle took place on 2 July, when nine people were murdered in a club in Envigado. Gunmen, believed to have been sent by Valenciano, sprayed automatic fire into a nightclub.

Their apparent target, an associate of Sebastian's known by the alias "The Fat Man", managed to escape.

As the violence has increased, the army has been deployed in some of the more violent neighbourhoods to protect the police, who are often outgunned by the street gangs.

They are commanded by General Alberto Mejia, who leads the Fourth Brigade based in Medellin.

"We are supporting to the police in their fight against the gangs, which are often armed with automatic weapons, grenades and explosives," said Gen Mejia.

Gangs

When it comes to knowledge from the ground, he calls on Capt Elkin Bernal, who knows one of the most violent neighbourhoods, the Comuna 13, intimately.

He commands 360 men split up among 15 bases around the notorious Comuna, spread out around its labyrinthine streets.

The "bases" are actually houses commandeered by the Mayor of Medellin in key areas of the neighbourhood.

"It is frustrating work here," said Capt Bernal as his troops zig-zagged through the narrow streets on motorcycles, stopping and searching the hard-looking youths that sit on the corners and in the bars that spill onto the streets.

Legally, his hands are tied as the army have few judicial powers with which to act in the city.

"We have had to wait up to two months for search warrants for places we know the gangs are operating from," Capt Bernal said.

Yet despite the army deployment, the murder rate is still rising. Unemployment is high, and the lure of drug money strong in neighbourhoods that have been providing workers for the drug cartels for more than 30 years.

This is the challenge Mr Santos faces.

The number of murders in Medellin during the first quarter of 2010 was even higher than in 2009.

To make matters worse, with the city's gangs weakened by their war, outside criminal groups are eyeing the prize of Medellin.

One group, the Urabenos, has already moved fighters into some of the key areas.

Another group, the Rastrojos, is said to have sent people on intelligence missions, looking for openings.

Without a new strategy, the urban war may be about to get worse.

- Published28 June 2010