How President Alvaro Uribe changed Colombia

- Published

Alvaro Uribe leaves a very different Colombia to his successor

President Alvaro Uribe may go down as one of Colombia's greatest presidents, with his policies for tackling guerrillas and drug-traffickers now a permanent fixture in the country.

"We were on the point of being a failed state," said Maria Victoria Llorente of the think tank Fundacion Ideas para La Paz.

"There was only one item on the political agenda and that was the rebels and security. He was the man for the job."

But for some, the success in taking on the rebels is balanced by a more negative legacy as Mr Uribe prepares to bow out on 7 August after eight years at the helm.

He has not been immune from political scandals and Colombia's relations with its neighbours are patchy.

For the majority of Colombians, though, security has been the key issue, demonstrated in recent opinion polls giving the president 75% approval ratings.

At the root of this popularity is one simple fact: President Uribe made Colombia a safer place.

In 2002, as a political outsider, Alvaro Uribe broke the monopoly on power the Liberal and Conservative parties had held for decades and won the country's top job.

A three-year peace process with the rebels of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) had failed and the guerrillas were stronger then they had been in almost 40 years of fighting.

Mr Uribe was voted into office on the back of a promise to defeat the rebels.

He wasted no time and has not stopped since he was welcomed by the Farc mortaring the president palace during his inauguration, killing 17 people.

His relentless offensives against the guerrillas seemed at times to reflect a personal hatred.

This is perhaps not surprising as Mr Uribe's father was killed by the rebels in 1983 during a botched kidnapping attempt and the Farc have tried repeatedly to assassinate him.

Over eight years he managed to beat the rebels back into the impenetrable southern jungles or up into the Andes.

In 2002, the Farc numbered up to 20,000 and their cousins in the National Liberation army (ELN) some 3,500.

Now the Farc have an estimated 8,000 fighters and the ELN perhaps 1,500.

Not only that, but kidnappings that once ran at more than eight a day have dropped to under one a day.

'False positives'

However, this success has not been without cost. Mr Uribe's administration, particularly during his second term, was beset by a series of corruption and human rights abuse scandals.

Alvaro Uribe: Release of Farc hostages was a moment of happiness

Perhaps the two most damaging were that of the DAS, Colombia's secret police, and an army scandal known as the "false positives".

The first head of the DAS, Jorge Noguera, was appointed by the president despite not having any police or intelligence experience.

He is now in prison, facing charges that include supplying lists of suspected rebel sympathisers to right-wing paramilitary death squads.

It also emerged that the DAS, which is supposed to answer only to the president, was intercepting the telephone calls of judges, opposition politicians and journalists.

The extent of the "false positives scandal" is still not fully known, but so far the attorney general's office is investigating cases involving more than 2,000 victims.

The "false positives" were civilians murdered by the army and dressed in rebel clothing to be presented as gunmen killed in combat.

The aim was to boost statistics and gain promotions for the soldiers involved.

"Uribe achieved this so-called security for us over the bodies not only of rebels, but of thousands of civilians. No judge, no jury, just a bullet in the back of the head," said Maria Solano, a seamstress in one of Bogota's southern slums.

Few friends

Foreign relations have not been a strong suit for President Uribe.

While he has maintained the close relations with Washington that he inherited from President Andres Pastrana, he has managed to isolate Colombia from many of its neighbours.

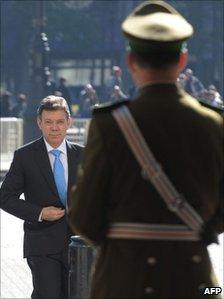

Successor Juan Manuel Santos is seen as more pragmatic

Venezuela and Ecuador do not have formal diplomatic relations with Colombia.

Nicaragua is also hostile and to a lesser degree so are Bolivia and Argentina.

The only Latin American nations that Colombia can currently describe as firm friends are Mexico, Peru and Panama.

Much of this bad blood dates back to 2008, when Colombian planes bombed a Farc camp inside Ecuador, killing 27 people, among them an Ecuadorean citizen.

One of Mr Uribe's last acts as president has been to take Venezuela to the Organisation of American States (OAS) and accuse President Hugo Chavez of sheltering rebels.

The result, predictably, was Mr Chavez once again severing diplomatic relations.

This bad blood with neighbours has also undermined an otherwise strong economic performance.

By opening up parts of the country previously dominated by the guerrillas he has created an oil and mining boom, attracting record levels of foreign investment.

However, both Venezuela and Ecuador placed restrictions on the import of Colombian goods, so damaging the economy, particularly along the border region.

'New sheriff'

Asked what were some of the highs and lows of his presidency Mr Uribe chose events that involved his sworn enemies, the Farc.

"There were some specific moments of happiness," he said, "like the rescue of the hostages."

This referred to a military operation in July 2008 when the army tricked the Farc into handing over 15 hostages they held, among them the former presidential candidate Ingrid Betancourt.

One of the low points was when it was discovered that the Farc had killed 11 local politicians kidnapped in the city of Cali, in Valle del Cauca province.

"I cried a lot, I was full fury and pain when I heard the news of the murder of the Valle politicians. Pain for their murder, rage for the lies of the terrorists," he said.

Mr Uribe hands over to his successor a vastly different country to the one he inherited.

Former defence minister Juan Manuel Santos has a great deal for which to be grateful to his former boss.

But he has already made it clear that Mr Uribe's authority ends on 7 August and that there will be a new sheriff in town.

- Published28 July 2010

- Published21 June 2010

- Published26 May 2010