How Peru's 'Andean rodeo' is helping save the vicuna

- Published

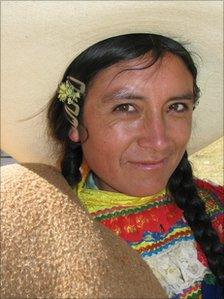

Dan Collyns joins the Chaccu

The Chaccu - dubbed the Andean rodeo - is a tradition from Peru's pre-Hispanic past that survives to this day.

But it is not just folkloric - the annual herding and shearing of vicunas plays a key role in helping to conserve Peru's most symbolic animal.

Just a few decades ago, the vicuna was hunted close to extinction on the high Andean plains where it roamed: for sport, for meat but mostly for its hide and its extremely soft and fine wool, said to be the best in the world.

In 1974 when it was put on the endangered species list the population was around 6,000; the latest estimate from 2008 put the population at close to 220,000.

A 1979 agreement between Peru, Argentina, Ecuador, Chile and Bolivia prohibited hunting and promoted the sustainable shearing of the animal's wool by communities in the high Andes.

The idea is that the communities protect the vicunas and, in return, benefit from shearing and selling their wool, which currently sells for around $300 per kg (a drop from $650 per kg in 2006).

Chaccus come in all shapes and sizes. The event in the village of Cushuro in the northern La Libertad region began six years ago after the community received 150 vicunas from southern Peru.

Vicunas are still at threat from poachers

The population has since grown to 600.

The event has also benefited from support from a mining company.

In 2008, the Minera IRL SA firm decided that the land which it had been exploring for gold was not viable but it promised to continue spending thousands of dollars a year on medicine and veterinary fees for the annual Chaccu.

"The project is still far from being self-sustaining," said local organiser Genaro Carrion, as he put sheared vicuna fleeces on the scales, each one weighing less than 150 grams.

"Without the company money, the Chaccu would simply not be financially feasible."

Mining executive Diego Benavides says the idea was prompted in memory of his father Felipe Benavides, a pioneering conservationist.

"The financial benefits to the communities from shearing the wool in this way far exceed those of selling the animals' hides on the black market," says Mr Benavides.

Elsewhere in Peru, Andean communities looking to turn the Chaccu into a business are faced with the same challenges but without the deep pockets of private benefactors.

Guards

Karina Santti, a vicuna specialist at the office for forestry management and wild fauna at Peru's agriculture ministry, says the onus is on the communities to "re-invest the profits from the vicuna wool into the animals' protection by training and equipping guards". There is no state help.

The Chaccu is also very much a social event

As a rule in the Peruvian Andes, the higher you go, the poorer people get.

While vicunas could be a valuable resource, projects are unlikely to get off the ground without help.

As part of a national decentralisation push, regional governments are now responsible for promoting the conservation and protection of their vicuna populations, with mixed results.

There is a particular lack of trained and armed guards to protect the vicunas from poachers.

Gangs driving pick-up trucks and armed with automatic weapons hunt herds of vicunas, often killing several hundred at a time, before skinning them and dumping their carcasses.

Close to a 1,000 vicunas are believed to have been killed in this way so far this year.

The Chaccu aims to be an example of how an endangered species can be protected and at the same time benefit the local people.

But Ms Santti says more needs to be done to improve the financial prospects for highland communities and directly involve them in the animals' protection before the vicuna is out of danger.