Profiles: Colombia's armed groups

- Published

Colombia's civil conflict has lasted more than five decades, drawing in left-wing rebels and right-wing paramilitaries.

The rebels have been weakened and the paramilitary forces officially demobilised. However, recent years have seen the emergence of criminal gangs who have moved in to take over drug-trafficking operations previously run by the paramilitaries.

The Colombian government says these criminal bands, which it calls "Bacrims", are now a major threat.

Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc)

The Farc is the oldest and largest group among Colombia's left-wing rebels and is one of the world's richest guerrilla armies.

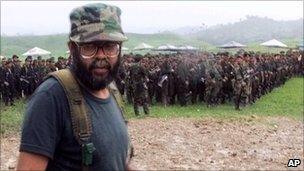

Alfonso Cano, the Farc's main leader since 2008, was killed in November 2011

The group was founded in 1964, when it declared its intention to overthrow the government and install a Marxist regime.

But tactics changed in the 1990s, as right-wing paramilitary forces attacked the rebels, and the Farc became increasingly involved in the drug trade to raise money for its campaign.

President Alvaro Uribe, who swept to power in 2002 vowing to defeat the rebels and was re-elected in 2006, launched an unprecedented offensive against the Farc, backed by US military aid.

The group had about 16,000 fighters in 2001, according to the Colombian government, but this is believed to have dropped to about 8,000, mainly as a result of desertions.

The Farc, which is on US and European lists of terrorist organisations, has suffered a series of blows in recent years.

The most dramatic setback was the rescue by the military of 15 high-profile hostages, including the former presidential candidate Ingrid Betancourt in 2008. The hostages had long been seen as a key element in the rebels' attempts to exchange their captives for jailed guerrillas.

The group's founder and long-time leader, Manuel "Sureshot" Marulanda, died that same year of a heart attack.

On 23 September 2010, the group's top military leader, Jorge Briceno, also known as Mono Jojoy, was killed in a raid on his jungle camp in the eastern region of Macarena.

In November 2011, Alfonso Cano, leader of the group since Marulanda's death, was killed in a bombing and ground raid in Cauca province. He was replaced by Rodrigo Londono, better known under his alias of Timochenko.

The rebels still control rural areas, particularly in the south and east, where the presence of the state is weak, and have stepped up hit-and-run attacks in recent months

However, in what was interpreted by analysts as a major concession, the Farc announced in February 2012 that it was abandoning kidnapping for ransom.

In November 2012, the Farc and the government opened peace talks, focussing on six key issues: land reform, political participation, disarmament of the rebels, drug trafficking, the rights of victims, and the implementation of the peace deal.

National Liberation Army (ELN)

The left-wing group was formed in 1964 by intellectuals inspired by the Cuban revolution and Marxist ideology.

It was long seen as more politically motivated than the Farc, staying out of the illegal drugs trade on ideological grounds.

The ELN reached the height of its power in the late 1990s, carrying out hundreds of kidnappings and hitting infrastructure such as oil pipelines.

The ELN ranks have since declined from around 4,000 to an estimated 1,500 to 2,000, suffering defeats at the hands of the security forces and paramilitaries.

However, in October 2009, ELN rebels were able to spring one of their leaders from jail, indicating that they were not a completely spent force.

In recent years ELN units have become involved in the drugs trade, often forming alliance with criminal gangs.

The group is on US and European lists of terrorist organisations.

Shortly after the Farc entered into peace talks with the Colombian government in November 2012, the ELN leader said that his group was also interested in negotiating a deal with the government.

The group was rebuffed by the president, who said it needed to show actions rather than words before it could sit down at the negotiating table.

Nine months later, after the release of a Canadian mining executive the ELN had been holding, President Juan Manual Santos said the government "was ready to talk" to the ELN.

He said he hoped negotiations could start "as soon as possible". So far, no more details about the framework of the planned talks have been released.

United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC)

This right-wing umbrella group was formed in 1997 by drug-traffickers and landowners to combat rebel kidnappings and extortion.

More than 30,000 paramilitary fighters demobilised under a 2003 peace deal

The AUC had its roots in the paramilitary armies built up by drug lords in the 1980s, and says it took up arms in self-defence, in the place of a powerless state.

Critics denounced it as little more than a drugs cartel.

The AUC's influence stemmed from its links with the army and some political circles, and its strength was boosted by financing from business interests and landowners.

The group carried out massacres and assassinations, targeting left-wing activists who speak out against them.

In 2003, a peace deal was signed with the AUC, under which paramilitary leaders surrendered in exchange for reduced jail terms and protection from extradition.

However, the Colombian authorities have extradited more than a dozen former paramilitary leaders to the US to face drug trafficking charges since 2008, saying they had violated the terms of the peace deal.

Some 32,000 paramilitary fighters have been demobilised, but the legal framework underpinning the process has been widely criticised for allowing those responsible for serious crimes to escape punishment.

Bacrims or criminal bands

The Colombian government regards the "Bacrims", as it refers to criminal bands, as the new enemy and the biggest threat to security.

The gangs, who include former paramilitary fighters, are involved in drug-trafficking and extortion.

In September 2010, a local think-tank, Indepaz, said a dozen or so new narco-paramilitary groups had quickly replaced the AUC in much of Colombia and were now responsible for more violence than left-wing rebels.

This echoes an earlier report in 2007 by the International Crisis Group, which highlighted concerns that former paramilitaries were joining forces with drug-trafficking organisations. , external

With names like the Black Eagles, Erpac and Rastrojos, they combine control of cocaine production and smuggling with extreme violence, but do not have any apparent political agenda.

The authorities believe in some regions they have joined forces with left-wing rebels to run drug-trafficking operations, while in other areas the new gangs and the guerrillas have clashed.