Brazil's education challenge in bid to be world player

- Published

State school pupil Eric wants to go to university to study engineering

Eric and Raquel live in Brazil's biggest city, Sao Paulo, but although their schools are just 40km (25 miles) apart, there is a world of difference in the education they are getting.

Raquel, 16, is in the last year at the private Colegio Vertice, where monthly fees are around 2,000 reais ($,1160; £740), twice the average monthly income. But there is a long waiting list of parents willing and able to pay for the best education possible for their children.

This year, Colegio Vertice's pupils scored the best marks in Brazil's national school exams.

"I feel that students here really want to learn. We have this goal, which is to get into university, and this goal drives us to study," says Raquel. "I am aware of what I have and of the opportunities I have and I am aware that great parts of Brazil's and the world's population don't have what we have."

The brightly painted school buildings spaced around shady courtyards are well cared for and decorated with pupils' art work.

Across town in Sao Paulo's poor eastern suburbs, Eric, also 16, gets ready for class. His home, overlooking a slum where drug dealers rule, is close to his school but it is a walk along poor streets and past burned out cars.

"Sometimes I see friends who don't want to come to class so I try to convince them to come with me. But many say it's no use because we learn nothing," says Eric.

Madre Paulina state school, where pupil performance was among the 20 worst in Sao Paulo last year, is a big, grim building covered with graffiti. Inside many doors, windows and desks are broken.

"Nobody here is motivated, not even the teachers. How can that happen? These teachers are the people who have to prepare the doctors and engineers for the future," says Eric.

Over the last 15 years, Brazilian government programmes have managed to achieve near 100% attendance in basic education from ages seven to 14.

This push began in the 1990s under President Fernando Henrique Cardoso, with thousands of new schools being built.

President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva's government continued and expanded schemes like the Bolsa Familia or Family Grant. Under this, more than 12 million families receive a monthly payment ranging from 22 reais ($12) to 200 reais ($116) as long as their children attend classes.

But ahead of Brazil's 3 October presidential, congressional and state elections, the quality of the education these children are getting is being scrutinised.

"Probably education is the most challenging constraint we have to growth," says Jose Pastore, professor of industrial relations at the University of Sao Paulo.

"The improvements over the last few years are real and they are fast but the accomplishments are still very small. Only about one third of the population in Brazil has secondary education, while in rich countries this reaches 75% to 80%."

Skilled workers

Brazilian workers have an average of seven years of basic schooling compared with 11 in South Korea, 12 years in the US and up to 13 years in parts of Europe.

"And they go to good schools while Brazilians go to bad schools," says Prof Pastore.

Government officials accept that the Brazilian education system needs improvement but say there has been real progress.

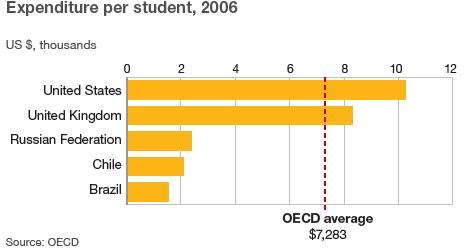

"State education has advanced a lot in Lula's government because we have been investing more money. We took an integrated approach from primary education to university and focused on better preparing our teachers," says Marcia Pilar, a top official in the education ministry.

"No country has ever managed to reform its educational system in less than a generation but we have been taking measures which already have an impact, such as the increase in the number of university students."

But Brazilian businesses say their need for skilled workers is immediate and a lack of trained staff is undermining the country's potential.

"There is a big demand for qualified workers, particularly in more hi-tech areas. We have been investing in our schools and modernising them to provide these badly needed professionals for the industry," says Walter Vincioni, director of technical schools in the state of Sao Paulo.

For Prof Pastore, Brazil needs to improve the status of teachers and recruit better candidates to the profession.

"If you don't have a good majority of teachers and principals, you have the results we have today. So if you test a Brazilian child after eight years of school, he has difficulty understanding what he reads, or doing maths."

Lagging behind

In Raquel's school, there is one teacher for every 10 students and 30% of them have master's degrees. Salaries are around 7,000 reais per month, a far cry from the average 900 reais a teacher in the state system earns.

Raquel studies at Colegio Vertice in the upper middle class neighbourhood of Campo Belo

Raquel has regular classes from 7am until 1pm, and then tutoring in the afternoon to help prepare her to earn a university place.

"This is the last year of high school so it's all about studying to enter a good university," she says.

Raquel has not decided yet if she wants to study biology or international relations. "What is important to me is to find something in my profession that will allow me to help other people," she says.

Eric has no doubts about what he wants to do.

"I want to be an engineer," he says, with the ultimate aim of working in Brazil's expanding oil industry.

But it is an uphill battle for the pupils of a school like Madre Paulina, where classes average around 45 to 50 pupils.

"How can I become an engineer with the kind of education I get?" asks Eric.

The candidates in Brazil's presidential elections have all said education would be a priority for their government, but they have not gone beyond general promises.

Eric studies at Madre Paulina State School in the poor suburb of Itaim Paulista, east of São Paulo

"I didn't hear from the candidates anything really interesting or concrete about education," says Prof Pastore.

"The big problem is that in a country where education has never been a priority, many parents are happy just because now their children are going to school and so, they don't demand more," he says.

"We need to find ways to bring the society together to fight for more quality in education. People in Brazil have to realise how important this is."

International studies show that the majority of Brazilian pupils lag behind not only developed countries but many other developing economies in basic skills.

Brazil has seen rapid growth over the past decade, but without a significant improvement in education and training of its workforce, it could fail to realise its full economic potential.