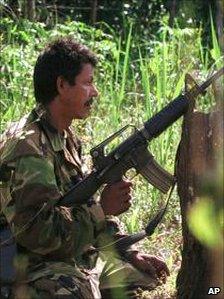

Colombia: Can the military bring peace?

- Published

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos has been in office for just two months but has already hailed the beginning of the end for left-wing rebels who once controlled large swathes of the country.

Two weeks ago, the military commander of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), Mono Jojoy, was killed during a large-scale military assault on his jungle stronghold.

The challenge for the government is to turn military success into lasting peace

It was the government's single strongest blow against the Farc in 45 years of counter-insurgency operations.

The challenge for President Santos is now to move from a major military success to peace - to turn a vicious cycle of violence into a virtuous cycle of conflict transformation.

This change could have happened at any time over the last four decades, had the parties to the conflict been serious in their struggle to reach a resolution for the benefit of the people.

Had successive governments been sincere in their commitment to defend Colombians from insecurity, they would have used their power to address the underlying structural problems in the country such as access to land and natural resources, inequity, and violent exclusion of critical voices.

Rebels would then have lost the narrative that sustains their struggle.

Had the Farc been more strategic, they would have invested in strengthening their soft power, that is, matching the means with the ends of their campaign, and living up to the international standards of conduct in warfare as well as developing their negotiation and dialogue skills.

Lost chances

None of this happened and, instead, peace talks have been hostage to calculations of military strength.

Both the rebels and government neglected the human costs of their approach in terms of killings, abductions, drug trafficking and massive displacement of populations.

President Juan Manuel Santos' success on the battlefield was compromised by major scandals

In 2002 the newly elected President Alvaro Uribe promised to wipe out the guerrilla forces during his term. He reframed the challenge from fighting an armed conflict to what he called a post-conflict scenario where the democratic institutions had to defend themselves from 'narco-terrorist' organisations.

With unprecedented popular support, the government's approach severely damaged the rebels' military capabilities, allowing people to enjoy freedom of movement in the cities and on major highways without fear of being kidnapped.

At the same time the government negotiated the demobilisation of right-wing paramilitaries and promoted the desertion of rebels, in exchange for leniency.

According to the government, more than 30,000 combatants have entered its reintegration schemes.

The government's success on the battlefield was nevertheless compromised by three major scandals that severely undermined the country's democratic institutions:

evidence of collusion between high-ranking government officials and their political allies with drug cartels and other forms of criminality

illegal surveillance of dozens of NGOs, journalists, politicians and members of the judiciary, carried out by the national intelligence agency

the extra-judicial killings of hundreds of young people from marginalised communities whose bodies would later be presented as rebel fighters killed in combat

Challenges ahead

The death of Mono Jojoy is a significant victory for the government.

It remains to be seen whether it is a victory for the Colombian people as well.

President Santos has committed himself to avoiding the dark side of his predecessor's legacy.

Peace talks provide a space for dialogue on national reconciliation

He is unilaterally addressing several points the Farc has recently asked to discuss at the negotiating table:

plans for increasing the number of US military bases are on hold

land restitution is now a government priority

the president has committed to acknowledge and support victims of state violence

political and economic reforms have been promised

If the president succeeds in this approach, he will be walking the path to peace.

Peace talks between the two sides are nevertheless still desirable.

This is not so much to allow political negotiations between the government and the rebels, but to provide a space for inclusive dialogue on national reconciliation and a transition to a post-conflict Colombia.

Trying to terminate an armed conflict by defeating the enemy is a high-risk gamble, with uncertain outcomes.

The huge costs are inevitably born by the people.

Addressing the structural problems and strengthening democratic institutions is a far more constructive, humane and even cost-efficient alternative.

Peace in Colombia is about respecting human rights: all human rights, of all Colombians.

To date, Colombian governments have neither wanted nor been able to take this approach seriously.

It is up the new Santos government, as well as to Colombian society, whether to choose the path that can lead to a sustainable and positive peace.

It is up to the international community - notably the US - to choose which approach they want to support.

- Published28 September 2010

- Published1 August 2010

- Published12 July 2010

- Published21 June 2010