Rio seeks to boost favela tourism

- Published

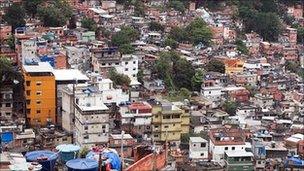

Favela tours may provide an alternative to Rio's well-known tourism circuit

Patricia Correia Capistrano looks out of the window above a row of shampoo bottles and hair products, scanning the street of Rio de Janeiro's largest shanty town, or favela, Rocinha, for potential customers.

Sensing a quiet afternoon, the 28-year-old hairdresser relaxes into conversation.

"The government wants to make the favelas safer for tourists because the view up here is amazing," she says, resting her arm on a salon chair.

"Everyone here is focused on the World Cup and the Olympics."

As Rio gets ready to host the matches in the 2014 World Cup and the Olympics two years later, the city's hillside shanty towns are the target of a government clean-up that in turn is being used as a springboard to develop tourism in the favelas with special tours.

Favela tours provide an exciting alternative to Rio's well-known tourism circuit of Sugarloaf Mountain, the Christ the Redeemer statue, and the beach. Built on steep hillside slopes, the favelas have breathtaking views of the city.

They also offer a unique glimpse of how some 20% of Rio's population lives, and an insight into Brazil's cultural and musical heritage.

"The favela has become part of the Rio postcard," says Eduardo Mielke, a tourism researcher, based at Leeds Metropolitan University in the UK.

Police presence

In the last two years, 13 of Rio's 1,000 or so favelas have seen a permanent police presence, known as the Police Pacification Units (UPP), which aim to drive out the drug traffickers that control the slums.

"By 2014, we'll take the UPP to all the communities in the state that are still controlled by criminals," Rio de Janeiro Governor Sergio Cabral said.

Some in the Rio favelas are already trying to promote tourism off their own back

"It is a new moment for Rio that will give visitors the freedom to get to know the city better."

In August, Rio's tourism ministry launched a programme in the Santa Marta favela - the first slum to become part of the UPP project - to train residents to become tour guides.

Since the creation of the Rio Top Tour project, the favela once ruled by the city's largest drug gang known as Comando Vermelho (Red Command) has become a tourism hub, with 4,500 visitors in the programme's first month.

Street signs in English have been placed throughout the community, and there are now 30 different tourist attractions, including a samba school, a local art gallery, and the spot where the Michael Jackson music video, They Don't Care About Us, was filmed.

"Before the UPP came in, Santa Marta was dangerous," says Daniella Greco, who volunteers in the favelas and works with a tourism company.

"The community is happy to have the tourists there - when you had [drug] trafficking, tourism didn't happen."

'Pacified'

Rio Top Tour is due to be extended to other favelas before the World Cup comes to Rio, although some have already used their own initiative to promote tourism.

Rocinha is home to some 250,000 people

Cilan Oliveira lives in the Pereira da Silva favela, where he works as an artist and a tour guide for Project Morrinho, external - a 350 sq m (3,800 sq ft) model of the favelas built by local teenagers.

"I love showing people this place because they get a better idea of our community," he says.

"I say to them, welcome to my community - relax, we are peaceful here."

Until now, the violence that plagues the slums has limited their tourist appeal to a few operators that market their tours to adventurous backpackers.

The government aims to open the favelas, once "pacified", to all types of visitors.

"The safer the place is, the more tourists you can attract," says Mr Mielke. "This is part of the government strategy - to use the favelas as another selling point of the city.''

Scepticism

But critics say that the government's plan fails to understand the complicated reality of favelas like Rocinha - which is home to some 250,000 people, and has operated outside the reach of the government since migrant workers started flooding into the shanty town in the 1950s.

Mr Cabral says the UPP will be brought to Rocinha by 2011, shrugging off concerns of a war between the drug lords and police that could last long after the games end.

"In Rocinha, a strategy is being drawn [up] responsibly," he says.

"The 'pacified' favelas are a showcase for the government," says Bianca Freire-Medeiros, a sociology professor at the Getulio Vargas Foundation in Rio.

"But many are sceptical about how long these supposed benefits will last once the World Cup and the Olympics are over."

Despite the uncertainty over the benefits of the government clean-up, favela residents like Humberto Alves de Barvollio are optimistic that tourism for the world's biggest sporting events will improve business in the slums.

Mr Barvollio's bakery has seen a rise in sales since becoming a pit stop for backpackers touring Rocinha.

"It has helped a lot since the foreigners started coming in," he says, handing custard-filled doughnuts to a group of tourists, "especially if they buy two or three things.''

- Published5 March 2012