Ecuador's Amazon drilling pledge still to take shape

- Published

.jpg)

Yasuni National Park and its wildlife attract several thousand visitors a year

Ecuador's Yasuni National Park is one of the most biodiverse areas in the world, containing as many tree species as the US and Canada combined.

Yet it is not a park ranger who greets visitors but an employee of Spanish oil company Repsol-YPF who registers those who come in and out.

That is because Yasuni contains another, more problematic, treasure: oil.

Oil exploitation has been taking place in parts of the park since the 1970s.

Yasuni's sounds and smells can be overpowering

When President Rafael Correa came to office in 2007, his administration began looking at ways of keeping newly-found reserves in the ground to try to keep Yasuni as pristine as possible.

Talks last August finally led to a pioneering agreement between Ecuador and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Ecuador pledged not to exploit the oil in the east of the park, which holds some 20% of the country's total reserves, in exchange for $3.6bn (£2.3bn) from national and international donors.

The proposal was hailed as historic by environmentalists, who believe it could lead to similar initiatives in other biodiverse countries, such as Indonesia, Brazil and Madagascar. But despite the fanfare, very little has actually been committed so far.

Key location

According to the conservation deal, Ecuador should receive at least $100m (£64m) by the end of 2011.

But since the fund was opened in August, Chile has given $100,000 (£64,000) and Spain has promised $1.3m (£840,000).

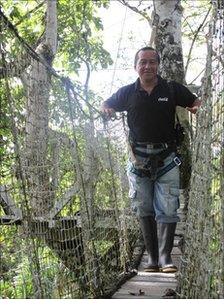

Guide Jose Macanilla says oil drilling causes irreparable damage

Yasuni's biodiversity stems from its location in the Eastern Ecuadorean rainforest at the intersection of the Amazon, the Andes and the Equator.

Thousands of species live in the park, but on arriving in Pompeya, where the Repsol checkpoint is, it takes some imagination to feel the diversity.

Along the road used by lorries carrying heavy machinery, the most exotic fauna on show are the wild pigs carried on the shoulders of hunters.

That changes quickly as you head further into the forest.

At the Tiputini Biodiversity Station, the most remote research station in the area, there is plenty of wildlife, although you have to be alert to spot hidden anacondas as well as tiny frogs.

But the sound of insects and birds is overwhelming, as is the pungent smell of monkeys.

Thanks to a project that uses motion and heat sensors to activate cameras, the station has managed to capture images of rare animals, such as the Short-eared Dog.

Long-term plan

Despite its environmental richness, Ecuador has little ecotourism. Yasuni, covering 10,000 sq km and policed by 12 park rangers, attracts just several thousand tourists a year, earning a negligible income.

.jpg)

Monitoring stations keep track of some of the rarest species

But Maria Fernanda Espinosa, Ecuador's Heritage Minister, insists that extracting oil from Yasuni is not necessarily the answer.

Yasuni is unique not only for its biodiversity, she says, but also because it is home to some of the last indigenous peoples still living in isolation in the Amazon - the Tagaeri and Taromenane nations, who belong to the Waorani ethnic group.

The government says it could make up to $7.2bn (£4.6bn) by exploiting the oil, and yet it is only asking for contributions worth half that amount to emphasise its commitment to preserving Yasuni.

"We're a country heavily dependent on oil exports and we're showing to the world that brave decisions are possible," Ms Espinosa told BBC News.

Under the UNDP-Ecuador agreement, external, donors pay Ecuador, which in turn promises to never exploiting the oil. If the government were to decide to extract the oil in the future, it would pay back the money to contributors.

The money, collected in a trust fund administered by the UNDP, would be invested in projects aimed at the local indigenous population and would help Ecuador move towards alternative forms of energy.

.jpg)

Whether the Yasuni agreement will work to conserve the area is still unclear

"It's a win-win situation," says Carlos Larrea, who teaches political economy at Quito's Universidad Andina Simon Bolivar and has been assessing the plan.

After a comprehensive economic analysis, he concluded that Ecuador would profit more by not exploiting the oil. His study considered factors such as the rainforest's key role in providing water to the rest of the country.

Ecuador has been drilling oil in the Amazon region for more than 40 years.

There have been several negative experiences, including a long-running and highly controversial lawsuit against Texaco , external(now owned by Chevron Corporation) for allegedly dumping billions of gallons of toxic waste in the rainforest., external

Nevertheless, oil companies have brought infrastructure, such as roads and medical facilities, and a source of income to these isolated areas that are often ignored by the central government.

Some indigenous people, including members of the Waorani ethnic group who are the park's main inhabitants and for years got salaries from oil companies, believe oil exploration and conservation work can be reconciled.

.jpg)

What price conservation versus development?

However, Jose Macanilla, one of the guides at the Tiputini Biodiversity Station and an indigenous Quechua who grew up north of Yasuni, is strongly opposed to any drilling.

"For us indigenous people who work in conservation, this is one of those projects that would destroy nature," says Mr Macanilla.

"We've already experienced that whenever oil companies open up new roads, over a short period of time everything is destroyed. The forest is ruined, species disappear, and the environment slowly changes."

Mr Larrea says years of oil extraction have not helped to reduce poverty in Ecuador. According to the latest UNDP Human Development Report, 41% of Ecuadoreans live below the poverty line.

The coming year will show whether Ecuador's big plan to enlist international funds to preserve its environment will actually work.

- Published4 August 2010