How landmines complicate Colombia's drugs fight

- Published

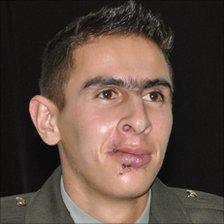

Rubiel Rodriguez: Owed his survival to his platoon's medic

Colombia is the most heavily-mined country in South America, with landmines used over the decades not only by the armed factions fighting the long-running civil conflict but by drug gangs keen to protect their valuable crop.

According to the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, Colombia trails only Afghanistan in the number of mine victims.

Since 1990, landmines have killed 1,938 people - some 63% of the victims were police officers and soldiers, according to Colombian government figures.

But many civilians have also been killed or injured, a significant number of them children, campaigners against landmines say.

The number of victims reportedly dropped in 2009 but drug traffickers are increasingly using mines to booby-trap their illegal crops, making manual drug crop eradication a risky task.

For years, the Colombian authorities used aerial spraying as their main weapon in the fight against coca production.

The size of the average coca field has diminished, but the crops are often hidden in the jungle

But drug growers and traffickers soon switched from growing coca in large open fields to using small, isolated plots, often next to legal crops such as yucca and banana, which were also destroyed by the spraying.

So the Colombian government has moved towards the manual eradication of coca plants, hiring locals to uproot each individual plant with a hoe.

But groups of eradication workers are also targets. They have armed police escorts to guard against attacks, but protecting them from landmines is far more complicated.

Suspicious activity

Major Jesus Enrique Quintero, 36, is the officer in charge of the manual eradication efforts in Tumaco, which has the highest density of coca plants in the country.

Jorge Emilio Salazar still bears the scars from the mine shrapnel

He has almost 700 police under his command and knows the dangers landmines pose only too well.

"Last year, one of my men was killed when he stepped on a mine," he says.

"And this year, I've had two men who had to have a leg amputated and one who lost his right eye after he was hit by shrapnel from a booby-trap."

He tries to take all the precautions he can, using a network of local informants and collaborators to tip him off when they see suspicious activity.

Before an eradication group moves into a field, his agents first secure the area. Police with sniffer dogs and metal detectors search for buried mines.

But a lapse in concentration can prove disastrous.

Jorge Emilio Salazar, a dog handler, was leading the team through the jungle to a coca field in the mountains.

"We had been walking for more than three hours and my dog was tired," he says.

It had been raining heavily, making it hard to walk through the knee-deep mud. Jorge Emilio stepped on a mine, which the dog had missed.

"You see, my dog was exhausted," he recalls sitting in a wheelchair, his left leg amputated below the knee and his right leg still full of metal surgical pins.

"Dogs are like humans, they can only keep their attention for so long. I had rested him for 20 minutes just before we got to the mine, I wish I'd given him a little longer."

First aid

Fast access to medical help is vital if landmine victims are to survive.

Rubiel is proud to belong to the police special operations team, the Jungla

As much of the eradication work is carried out in Colombia's dense jungle, it can be difficult to get the injured to the nearest hospital quickly enough.

Rubiel Rodriguez is grateful to the medic in his police special operations team, called the Jungla, or Jungle Squad. "The guy was great, he saved my life," he says.

Rubiel, 26, stepped on a mine in Vistahermosa, in Meta province. He was conscious throughout the hour it took for a helicopter to airlift him out of the jungle.

Rubiel says the medic calmed him down when he saw that his foot had been blown off.

"He told me I'd be fine, that I'd survive, that I had nothing to worry about," he says. "He even joked around, and that made me think it couldn't be that bad."

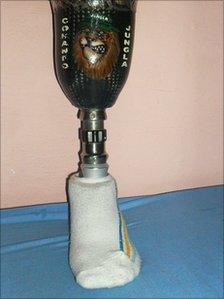

Eighteen months after his accident he has made a remarkable recovery. His prosthetic leg, emblazoned with the word Jungla, gives him almost total mobility.

Rubiel says he wants to continue fighting the drugs trade and will stay with the police.

Life-saving training

Amir Tique, 25, did not have a medic to help him when he had his foot blown off in Tambo, in Cauca province, on 22 June 2010.

Amir Tique performed first aid on himself when he stepped on a mine

He was the medic.

Confused by the explosion he had set off, he opened fire on the surrounding hills, thinking he had come under attack from left-wing rebels.

It was only when his commander shouted to him that he had stepped on a mine that he looked down and realised what had happened.

Amir knew he would have to perform first aid on himself.

He applied a tourniquet to his injured leg, inserted an intravenous drip into his arm and medicated himself with pain-killers and antibiotics until his colleagues had checked the area for mines and could approach.

They built a make-shift stretcher for Amir and carried him to the Blackhawk helicopter that airlifted him to the nearest hospital.

Being killed or maimed by a mine is a risk police and civilian eradicators have to face every day, says Jose Roa, the major in charge of the programme.

So far this year, 10 police, nine civilians and seven soldiers have been killed.

"It's a silent killer which stalks us and threatens us, and yes, we can admit it, frightens us," one of his men wrote in a letter.

"The mines are our torment, but they won't intimidate us."

The letter lies on Major Roa's desk at Anti-Narcotics Police Headquarters in Bogota. The next day he is called away to San Jose del Guaviare, in the east of the country.

Four of his men have been ambushed and killed by left-wing rebels after they walked into a minefield.