Why Brazilian film Elite Squad 2 is a box office hit

- Published

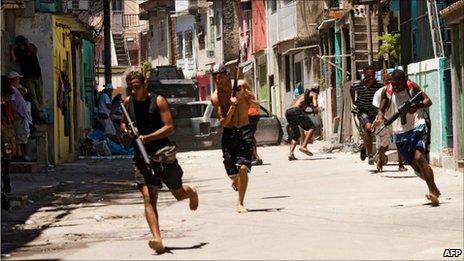

Armed men run through a favela in a scene from Tropa de Elite 2

As 2010 draws to a close, Brazilian cinema is reflecting on a success story that has broken a 34-year old box office record.

Since 1976, the country's most popular national film had been a love story, Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands, seen by more than 10 million cinema-goers and thought to be virtually unbeatable in the box office.

But this month, a gritty movie about police corruption in Rio de Janeiro's shanty towns overtook Dona Flor's total and seems set to soon pass the 11 million mark.

The film, Tropa de Elite 2: O Inimigo Agora e Outro (Elite Squad 2: Now We Have Another Enemy), is a sequel to the 2007 hit, Elite Squad.

The success of Tropa de Elite 2 reflects the transformation that Brazil's film industry has undergone gone in recent decades, moving from a politically censored environment to hyper-realistic accounts of social and political issues.

Role model

Part of the film's success is the result of a commercial strategy. Before the film's launch, the production company waged a strong anti-piracy campaign to prevent illegal copies from reaching the internet.

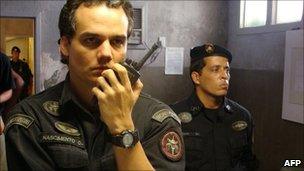

Captain Nascimento, the central character, divides opinion

The first Elite Squad leaked before its release in 2007, and it is thought that more than 11 million people watched a pirated copy - which ironically would have broken Dona Flor's record three years ago.

But much of the success of director Jose Padilha's sequel can be attributed to all the controversy and praise that his original film received.

The first Elite Squad is regarded as a powerful interpretation of Rio de Janeiro's complex police issues and is cited by numerous scholars and authorities whenever real life events unfold in the city, such as in last month's police operation in the Complexo do Alemao favela.

The first movie introduced Brazilian audiences to Captain Nascimento, a police officer with a self-righteous approach to crime-fighting. He had no qualms about torturing and murdering drug traffickers in his struggle against organised crime in the favelas.

Elite Squad, set during a papal visit to Rio in 1997, sparked a nationwide debate on the consequences, and flaws, of two approaches towards Brazil's war on organised crime.

Some viewers saw Capt Nascimento as a criminal, no different to the people he was pursuing.

However, to the dismay of Padilha, who originally intended Nascimento to be an anti-hero, the character became a role model for many Brazilians, who loved his unlawful, yet efficient, way of dealing with crime.

Worse than criminals

The sequel takes place 13 years after the events of the first movie, but the same dilemma persists.

Capt Nascimento is in charge of dealing with a prison rebellion. The police have the means to end the mutiny peacefully, but one of Capt Nascimento's officers sees the rebellion as a chance to kill an important gang leader, after he has already surrendered.

Capt Nascimento is denounced by a human rights activist who was in the prison trying to negotiate a bloodless outcome. Criticised by the media and the government, Capt Nascimento is immediately fired. However, in his first public appearance, in a posh Rio restaurant, he receives a standing ovation from members of the public.

Thirteen years later, Rio is still divided about Nascimento: is he a hero or a villain?

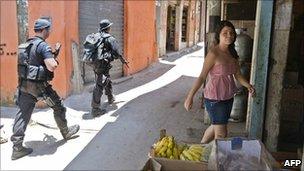

And in an echo of real life, police in the film successfully expel criminals from a favela. But instead of bringing peace to the community, this creates a power vacuum.

Who will run the favela's many other non-drug related businesses, that were all previously under the criminals' grip - from illegal cable TV subscriptions to street policing? Corrupt police officers soon form militias and take over the favela, proving to be even more ruthless than the original criminals.

Tropa de Elite 2 runs many parallel stories that meet in the end: Nascimento's rise politically, a reporter trying to uncover the story, politicians running for office and getting support from militias, parliamentary inquiries and family dramas.

Like the first movie, Padilha paints a rich and comprehensive picture of Rio's cycle of violence. But this time he is unambiguous and leaves fewer questions unanswered.

Capt Nascimento gradually renounces his old methods and joins calls for a more law-abiding approach towards tackling crime.

Tropa de Elite 2 also takes aim at the Brazilian Congress and the federal and state governments - for, at best, failing to tackle the social issues behind the violence and, at worst, for colluding with criminals for political gain.

Challenging cinema

Tropa de Elite 2 is radically different to the previous record holder, Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands.

Last month Rio police launched a big push to retake control of some shanty towns

Dona Flor, inspired by a bestselling novel by Brazilian author Jorge Amado, is a fictional account of a woman torn between two loves: her current husband, an older gentleman, and her deceased first husband, a young vagabond, whose spirit is only seen by her.

It is almost naive, with some echoes of Latin American magical realism, and completely apolitical. When it was released in 1976, Brazil was going through one of the darkest eras of its military dictatorship.

In the 34 years that separate the films, Brazil went through radical change.

In 1989, the country elected its first civilian president in four decades. The political climate eased, but economically Brazil's film industry was on its knees after the relative prosperity of the 1970s.

In 1992, only one Brazilian film found enough funding to be released.

Both Tropa de Elite films belong to a new realistic trend of cinema that began in 2002, the year that saw the release of the internationally acclaimed City of God and the documentary Bus 174.

Over the past decade, film directors have taken advantage of more generous funding to engage in political critiques that seem to resonate with Brazilian audiences.

After years of censorship, Brazilian cinema is now enjoying commercial success by making the most of its freedom to criticise and challenge.

- Published28 November 2010