New life, new challenges for Chile's hero miners

- Published

On 14 October, the last of 33 miners was brought safely to the surface after spending 69 days trapped underground in the San Jose mine in Chile's Atacama Desert. The BBC's Piers Scholfield has been back to Copiapo to find out what life has been like for the men since their high-profile rescue.

"It's still difficult.. most people think the miners are out having fun and earning lots of money - but what we went through will mark us forever."

Claudia Jimenez sits beside her father-in-law, Omar Reygadas, as they talk about the last couple of months.

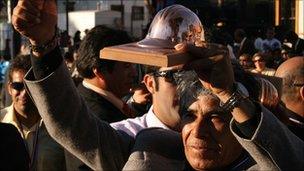

Omar was the 17th miner to step out of the specially-designed "Phoenix" escape capsule during the spectacular rescue that captured the world's imagination - a global audience of hundreds of millions watching on television.

Omar's family spent much of the 69 days the men were trapped travelling to and from Camp Hope - the tented village outside the mine's gates - juggling work and family commitments to make sure that some of them were close by for as much of the time as possible.

Claudia's 11-year-old daughter, Rocio, can't help but let out tears when she casts her mind back to her grandfather being underground.

"I never imagined I might not see my grandpa again," she sobs.

It was his family who got him through the ordeal, Omar tells me. And his family are ever-present now, helping keep his feet on the ground after two months in the media spotlight.

Psychological problems

The 33 men have been to Spain, Hollywood and Manchester (to see Manchester United play). They have trips coming up to Disneyworld in Florida, Israel and Greece.

But despite being much in demand internationally, the men's lives are complicated. After having been underground for so long, many of them have long-term psychological problems.

"I can never get to sleep before 0400 or 0500," Omar tells me. "And I hate being alone - I often find myself crying."

He says he's taking medication to help keep him stable and trusts in the doctors' assertions that his condition will improve soon.

But until then he needs his family nearby whenever possible.

"There is a big danger of depression," says Adib Merlez.

He's a psychologist at Copiapo's Universidad del Mar. He and his colleagues will be offering therapy to the miners next year he says, once the situation has calmed down.

"At the moment, some of them are obsessed with the media," he says.

He cites the example of Franklin Lobos - one of the miners who played for Chile's national football team when he was younger, but went into mining after a stint as a taxi driver in Copiapo.

Omar Reygadas finds it difficult to sleep since his ordeal at the San Jose mine

"He's changed, and not for the better," says Mr Merlez. "Before the accident I often talked to him. But now he doesn't have time for us."

In a few months, he believes, things will change. And he and his colleagues will be there to help.

"We can help bring them back down to earth," he says.

Family feuds

Some of the 33 men have already come down to earth.

Despite dreams of untold riches, their experience hasn't necessarily translated into concrete wealth.

Soon after the rescue, an eccentric Chilean billionaire, Leonardo Farkas, gave each of the miners a cheque for $10,000 (£6,400).

That money - and promise of more - put enormous pressure on the men as soon as they were out of the mine.

Some found that their extended families grew somewhat. And there are sad tales of family feuds as a result.

One of the 33, Claudio Yanez, married his fiancée, Cristina, just this month. She had raised a few eyebrows by proposing to him while he was trapped underground.

After leaving the hospital following the rescue, Claudio snubbed his mother and went straight to Cristina's house - for which his mother never forgave him. None of his family attended the wedding.

But despite numerous stories of book and film deals, few of the men have yet seen much profit.

Carlos Mamani, the only Bolivian in the group, still lives with his partner and baby daughter in a basic, run-down shack on the outskirts of Copiapo, with no running water.

And most of the others are living on medical insurance payments, arranged after the rescue.

There are success stories. Edison Pena, the avid Elvis Presley fan who ran several kilometres underground every day, has since his escape run the New York marathon and appeared on David Letterman's chat show in the US.

He has recently been in Italy, where he was due to sing a duet with Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi on prime time television.

Envy

And others are going about earning their keep in a quieter way.

Omar Reygadas, at 56 one of the older miners, and Mario Sepulveda - who became famous whilst still underground as he guided a camera round the men's living quarters - have been on a tour of the country, giving motivational talks to students.

Mario Gomez, the oldest of the 33 miners, enjoys the opportunities to travel that have come with fame

"We tell the students about how we got through the ordeal," says Omar. "It was by working together - being unified - and because of our faith in God."

But there is a sense of envy amongst some of the other men towards them - which Omar is only too happy to admit.

"They are a bit annoyed with us for earning money," he says. "And we don't feel good about it - but nor can we force the organisers to invite all of us to speak."

Over the last two months the miners - from working class backgrounds and mostly with very little education - have received little advice on how to deal with the media.

"They think they can charge money for a five-minute chat on the phone," says Omar. As a result, the media have become wary of dealing with the men.

Omar says he tries to help. "I offer them advice - but some of them don't want to accept it."

But interest in the men's extraordinary story continues.

There are potentially at least two films in the pipeline - one by a Chilean director, the other a Hollywood production, lead by Brad Pitt's "Plan B" production company.

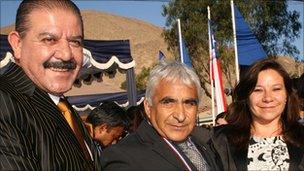

At Copiapo's anniversary parade, earlier in December, the cameras of the international media were still much in evidence.

As military bands played in the early summer sunshine, local children entertained the crowds with their dancing in colourful traditional Chilean costumes.

And the guests of honour were some of the "Atacama 33," who each took their turn to be presented with awards for heroism by the city's colourful mayor, Maglio Cicardini.

Omar Reygadas's family helps him to keep his feet on the ground

Job offers

The mayor - a larger than life character with a long grey ponytail - played a high-profile role during the rescue, spending a lot of time up at the San Jose mine.

He's keen to dismiss concerns that the men haven't been given guidance on how to manage their newfound fame.

"We are working with them to help them return to normality," he says. "And the government has offered them all work. Every single one of them."

The government gathered most of the 33 men together in the capital Santiago early in December.

In a day-long meeting they were offered work with Codelco, the state-run copper mining firm who oversaw the rescue process.

The government also arranged the help of a law firm to help make sure the men earn their fair share of proceeds from any Hollywood film deal.

But some relatives feel the government is abandoning them.

Liliane Ramirez is the long-term partner of Mario Gomez, who at 63 was the oldest of the men trapped underground.

"He can't go back to work because he's in a bad way," she says. "Psychologically he is unwell - he has constant headaches and he's losing his hair."

According to Liliane, the government has said the men's medical insurance payments will stop if they continue to travel around the world. But that won't stop Mario.

"He told me that if he he's not allowed to work, he'll travel. He's worked all his life. If he can't travel, he'd have nothing to do."

The story of the "Atacama 33" is far from over.

After surviving 69 days deep under the desert in treacherous conditions, they will need still more reserves of strength and fortitude to complete the long transition to a normal life.