Haiti earthquake: After so many promises, why is the country still struggling?

- Published

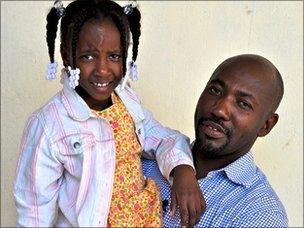

Telia Jacques: Smiling again after the horrors of the Haitian earthquake

Once in a while, you visit a place that you know will forever be lodged in your mind.

That place for me is L'Hopital de la Paix, on Delmas 33, Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

I first went there just about 24 hours after the earthquake on 12 January last year.

Now, a year later, walking into the hospital grounds, it all comes back.

It was a clear night, as the stars shone down brightly out of a dark Caribbean sky.

There's the kerb against which I saw a baby's body lying wrapped and abandoned.

There's the grass leading up to the main building, where I watched a man lay down to sleep between two dead people.

There are the steps that take me through the entrance, and back into the corridor down which a woman's wail echoed, where a girl wrapped in bloody sheets lay curled up on a table.

And there's the corner where Astrel Jacques first introduced me to his daughter.

Telia was lying on the tiled floor, her little legs broken, the dirty bandages on her head barely stopping the bleeding from a large gash.

Now, here we are again, the three of us, at the same corner a year later.

Telia's hair is in braids, each finished off with a white plastic clip.

The scar across her forehead, running down from hairline to eyebrow, is still vivid. So, too, the scars on her legs. She will always have those. But today at least she can smile, and she has a beautiful smile.

"As I'm walking right here, you had to step on dead bodies. Dead bodies was everywhere," Astrel recollects in broken English as we head along the now pristine corridors.

"Mothers, daughters, fathers, sons: everybody was just fighting to stay alive."

Telia's father says she is still traumatised by the events of a year ago

Telia is a quiet girl. Her father says she is still traumatised.

She was injured by falling masonry when the earthquake hit. Her younger sister was killed. So, too, was her grandmother. The scars, physical and mental, will be with her for the rest of her life.

But will Haiti too be scarred forever? Twelve months ago, as I walked past the dead, as the smell of decaying bodies grew more pungent day by day, there was not much to be positive about.

There were, however, some signs of encouragement. One was the sheer level of support and help offered from around the world. Compassion fatigue? Hardly. Haiti caught the world's attention, and benefited from the world's generosity.

Then there was the resourcefulness of the Haitians themselves. They managed to return to some sort of basic existence pretty quickly.

There were the international promises to re-build a better Haiti - everyone seemed to agree, and the momentum was building to do just that.

Frustration

Today though, back on that hospital corner, Astrel Jacques is no longer encouraged.

"As of right now, Haiti will never rebuild. I mean I don't see any sign. For something to rebuild you have to see signs. You have to see hands put in. You have to see actions. You have to see talks. I don't see any of it."

It is a common refrain, born somewhat out of reality, but also out of frustration.

There have been changes here, but so far they have been limited.

In those days after the earthquake, I visited a supposedly temporary camp Next to it was a patch of empty, stony ground. I wondered how much longer it would be before the tents and tarpaulins spread out from the camp to cover it, too.

A month later, when I next saw it, people were indeed beginning to put up rough wooden structures. A few poles and bit of plastic sheeting.

After six months however, as I next passed by, the land was empty, a fence around it. A waste of space it seemed.

Now, there are 350 new homes there. Wooden structures, and temporary, but the people who moved in over the last few days consider themselves lucky. They finally have something more than a tent that they can call home.

'I can't rebuild'

The issue many here have is that even this is not a long-term solution. It took the International Red Cross a year to get permission to use the land, to secure it, to get the materials, to move people in.

And yet there are no paved roads in what is Port-au-Prince's newest neighbourhood, no sewage infrastructure, no electricity. Within a year this may well be Port-au-Prince's newest slum.

This kind of rebuilding is also the exception. Much rubble is still lying where it fell.

In a crowded district, which sits in the fold between two hills, many of the ruins I climbed over a year ago are still there. As I wind through the tiny alleyways, there are some signs of clearance.

Outside Fabula's tin shack for instance, the mound we stood on six months ago has been cleared, leaving an empty plot where one day someone will build.

Fabula's son is now one year old. I met him in the first few minutes of his life. He was born just after the earthquake. His mother, too exhausted to push him out, almost died in labour.

Her life is still immensely hard.

"Nothing has changed," she says.

"The people who are fortunate have done some small rebuilding, but the unfortunate have not done anything. My mum lives up the hill in a camp. I still can't rebuild our house."

Pushed to the limit

Haiti is the kind of place that gets under your skin.

It plays with your emotions.

I have spent much of the past week here feeling angry. Why has seemingly so little been achieved?

Fabula's son was born just after the earthquake

You can point fingers in many directions. At the government and its weak leadership - but then 17% of its civil servants died in the earthquake, and it was weak anyway.

At the international community, for failing to live up to their promises, but then all agree this is one of the most complex humanitarian disasters of the modern age, and addressing it is going to take decades.

At the NGOs - of whom there are thousands here - for failing to start longer-term projects, but then they have been pushed to the limit by other challenges, a hurricane and a cholera epidemic. They have kept Haiti alive on life support.

The challenge remains though, to move this country off emergency care, and into long-term rehabilitation.

The big stuff needs to be addressed.

A more able political leadership needs to be established. Infrastructure projects need to be planned - new streets, a sewage system and power grid. Jobs need to be created. Houses built. An entire country needs to be recreated.

How though, do you do that? Let's hope in a year's time we're not still asking the same question.