Mexico's struggle to stem looting of historic sites

- Published

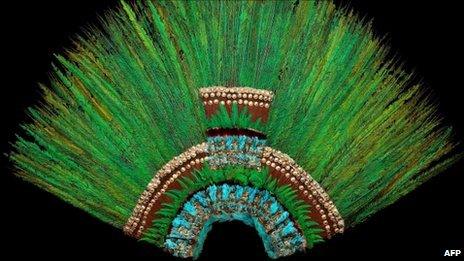

Aztec treasure: Mexico has long wanted to see the original returned

It is a spectacular work of art and a highlight at Mexico's National Museum of Anthropology.

The semicircle of gleaming green feathers held together by rows of golden beads was, it is said, the headdress of Mexico's last Aztec ruler, Moctezuma.

But the spectacular artefact is not real - it's a replica. The original lies thousands of kilometres away in a collection at Vienna's Ethnology Museum.

The exact origin of the headdress or "penacho" is disputed but one version says Moctezuma gave it to the Hernan Cortez, leader of the Spanish conquistadors, in the 16th Century. By the twists and turns of history, it ended up in Austria.

Nearly 500 years on, the original may be loaned temporarily to Mexico, a development that has created expectation there and highlighted the country's historic riches.

But the pre-Hispanic artefacts and sites not only attract tourists; looters and traffickers see a chance to profit from the wealth of the past.

Now the authorities are looking at various ways of clamping down on this trade in relics of their nation's history.

There are an estimated 200,000 archaeological sites in Mexico - among them, the Mayan ruins and pyramids in the country's south, the Paquime mud-based constructions in the northern state of Chihuahua and the huge complex of Teotihuacan, north of Mexico City.

Examples of the ancient relics found at Teotihuacan

The government admits that just 40,000 archaeological sites are properly registered; of those, only 160 are supervised and open to the public.

Most sites are unsupervised, with many located on private property or in remote locations. They are vulnerable to those who illegally extract artefacts to sell on, sometimes for thousands of dollars.

The battle against the illegal trade is made even harder because there are no official estimates of the number of pieces being smuggled.

The International Council of Museums, an association of museums and museum professionals that safeguards heritage, published a Red List, external in June 2010 of works it considered at risk.

ICOM warned that the pre-Hispanic and colonial cultural heritage of Mexico and Central America was "severely endangered".

Mexico signed an international treaty in 1972 that prohibits the extraction and trade in archaeological artefacts, with punishment of up to 12 years in jail for such a crime.

But, almost four decades on, experts say the demand from abroad for pre-Hispanic pieces, especially the US, shows no signs of abating.

Sophisticated business

Looting of archaeological sites often begins at a local level, according to Mexican officials.

Looting is becoming increasingly businesslike, officials say

In some cases, inhabitants of Mexico's poor rural communities come across pieces and decide to sell them to earn extra income. The middlemen who buy the artefacts then offer the goods to private collectors or art traders.

But the business is getting increasingly sophisticated, with criminals taking advantage of the lack of supervision of thousands of sites.

"The problem is professional looting," says archaeologist Enrique Vela, editor of Arqueologia Mexicana, a leading archaeology magazine.

"These are networks that have capacities that sometimes us archaeologists don't even have, of digging in some areas because they know exactly where the objects will appear," he said.

The government has succeeded in intercepting some of these networks; last July, in raids around the country, it recovered 180 archaeological pieces believed to be in the process of being smuggled abroad.

Fakes

In 2008, the government created a dedicated inter-departmental unit to deal with the cases and to start creating a database of missing artefacts.

Authorities are also trying to stop the sale of items in international auction houses.

"As soon as we hear that an auction house is selling one of these pieces, we launch an effort, both judicial and diplomatic, to notify the auction house that it is committing a crime and that the sale must be stopped," says Rene Salazar, from the attorney general's office.

Mexico's rich history is a draw for visitors

But Mr Salazar admits that differing national laws and the lack of reliable figures about the number of artefacts being smuggled every year complicate those efforts.

In fact, a simple search at online auction sites throws up several results of alleged archaeological pieces from Mexico.

It is impossible to know whether these are authentic - fakes have also flooded the market, authorities say - but the concern is that the trafficking is too widespread to control.

The government has launched campaigns aimed at children, asking them to help to save the country's rich heritage.

The hope is that the battle against archaeological looting will be boosted if the younger generations are taught the importance of their country's past.