Colombia hostage releases: Breakthrough for peace?

- Published

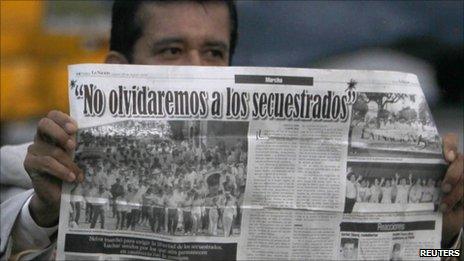

The Colombian government insists all hostages must be freed

Over the past week, Colombian rebels have freed a total of six hostages - the final two men being handed over on Wednesday. The BBC's Jeremy McDermott in Bogota looks at what lies behind the guerrillas' actions and whether there is a real prospect for peace.

The men freed by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), Latin America's most powerful and longest running guerrilla group, included four members of the security forces and two local politicians.

The Farc had previously hoped to swap their captives for jailed rebels. So with these releases and the promise of more to come, the rebels are paving the way for peace talks with President Juan Manuel Santos, offering the prospect of an end to almost 47 years of civil conflict.

However, the government appears in no hurry to negotiate and condemned the way the releases had been handled.

"The government profoundly laments that the Farc have used these releases for political propaganda... to abuse the pain of the families and of the Colombian people," read an official statement.

Despite the tough words, there are some grounds for optimism.

The last attempt at peace talks ended in abject failure in 2002. The then government of President Andres Pastrana was in such a weak negotiating position that the Farc were able to take control of the talks and demand a 42,000 sq km (16,200 sq mile) safe haven as the venue for negotiations.

They then used this area to build up their military strength and boost their finances through drug trafficking, kidnapping and extortion. The Farc forces were at the height of their power in 2002, with 16,000 fighters and more than a third of Colombia under their control.

Losing ground

The Farc today are a very different organisation. They are believed to have just 8,000 fighters and have been pushed out of their encampments around the major cities and into the dense jungles and high peaks of the Andes.

The plight of the hostages resonates in Colombian society

While they still have money, thanks to the drugs trade and extortion, it is nothing like the $350m (£220m) that they were believed to be earning in 2002.

Three members of the seven-man secretariat, the Farc's ruling body, have been killed in the last three years - two in aerial bombardments and another by his own bodyguard, who claimed a government reward for his boss's head.

The legendary leader and founder of the Farc, Manuel "Sureshot" Marulanda, also died, of natural causes, in 2008, which was a huge blow to the rebels' morale.

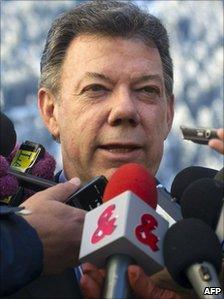

Now the government has the upper hand and it is clear that Mr Santos will not allow the Farc any room for manoeuvre.

"Colombia has suffered a lot due to guerrilla tricks. I have said that I need much more than the liberation of six hostages to show me that there is a real desire for peace... many times they have used these dialogues and negotiations to strengthen themselves again," Mr Santos said.

However, he has said the "door is open" and there have been some key changes over the last few years which suggest that dialogue, while not imminent, is a real possibility.

Ready for talks?

Firstly, Alvaro Uribe, who was president from 2002 to 2010, is no longer president.

Dialogue between the Farc and Mr Uribe was almost unthinkable. The former president's father was killed by the Farc in a botched kidnapping attempt and there was the perception that his relentless offensives against the rebels, which had the full backing of President George W Bush in Washington, were something of a personal crusade to wipe them out.

President Santos has adopted a tough but not inflexible stance

Secondly, President Santos has demanded the release of all hostages. As this is a real possibility, it could allow the government to justify the start of a peace process.

Thirdly, under the new leadership of Guillermo Leon Saenz, better known by his Farc alias of Alfonso Cano, the rebels have changed their negotiating position, including dropping their demands for a prisoner exchange.

However, they do still kidnap for ransom, a source of funding for many of the rebel units that do not have access to drug crops and this may well prove to be a stumbling block later on.

The rebels have also dropped their condition for talks, which was the granting of another safe haven, free of government troops and state presence.

In a video published on You Tube in July 2010, Alfonso Cano said that the Farc were ready to negotiate.

"We are proposing anew today, yet again: man, let's talk," he said.

This was followed up in November by a communique published on the rebel-affiliated Anncol website, entitled "The only valid option is a political settlement", which set out the Farc's negotiating agenda.

Daniel Garcia-Pena, a former government negotiation and peace mediator summed up the possibilities for a negotiated settlement.

"We are in a much more positive moment than before. President Santos has not double-locked the door, but rather we are in a position which could permit in the medium to long term, the possibilities for peace."

- Published16 February 2011

- Published14 February 2011

- Published27 May 2013

- Published14 February 2011