Colombia's criminal bands pose new security challenge

- Published

Criminal bands have forged alliances with former foes

Those that venture out in the evening in Caucasia sit with their backs to the wall.

It is not drive-by shootings that frighten people, although they do happen, but the attacks with grenades, which happen all the time.

"I get myself and my boy in the house by 1800," said Maria Duvan, who sells coffee outside the mayor's office.

"The paras offer the young lads a good wage, right up until they end up dead."

The "paras" she speaks of are the new generation of paramilitary drug cartels.

The government call them Bacrims - short for criminal bands - to distinguish them from their paramilitary predecessors, the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC).

The AUC was a right-wing umbrella group formed by landowners and drug traffickers in the 1990s to combat Colombia's left-wing guerrillas

Though effective in fighting the rebels, it was heavily involved in drug-trafficking and committed widespread human rights abuses, including forced displacement and massacres of civilians.

Peace postponed

The AUC demobilised in 2006 under a peace agreement with the government, and around 30,000 fighters surrendered their weapons.

But many paramilitaries quickly returned to what they did best: smuggling drugs.

And it is here in the town of Caucasia where the latest chapter in Colombia's drug war in being fought.

This town sits in a valley, astride the main road linking the centre of the country with the Caribbean coast.

The Andean mountains on either side are covered with plantations of coca leaf, the raw material for cocaine.

Whoever controls Caucasia, and the surrounding region of Bajo Cauca, controls access to the coca harvest and drug smuggling routes north to the Caribbean and west to the Pacific Ocean.

Two of the most powerful Bacrims - the Urabenos and the Rastrojos - are battling for supremacy.

The murder rate in Caucasia is 224 per 100,000 inhabitants, one of the highest homicides rates in the world.

On 13 March, the security forces came across 10 fresh corpses in the countryside outside the town, among them a child and a woman dressed only in her underwear.

The police believe they were somehow linked to the drug trade and had crossed the local Rastrojos leader, Angel de Jesus Pacheco Chancy, alias Sebastian.

Once a member of the AUC, he refused to turn himself in when the paramilitary army demobilised, allying himself with the Rastrojos as they sought to take control of the drug trade in the region.

Revived menace

In the fifth decade of Colombia's civil conflict, the Bacrims have replaced the Marxist rebels as the primary generators of violence.

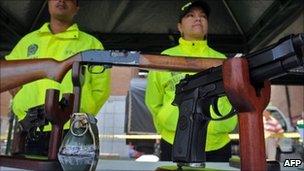

Colombian soldiers are now having to train their sights on the Bacrims as well as guerrillas

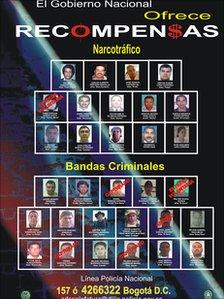

They have also become the priority targets for the government and the security forces.

The area around Caucasia has become the principal focus of the armed forces in the whole country.

In February, Defence Minister Rodrigo Rivera launched Operation Troy to tackle the estimated 1,000 Barcrim members who operate here.

An extra 1,000 police and 3,000 soldiers have saturated the region.

So far they have made some low-level arrests, but the violence continues.

Driving into the town one has to pass through military checkpoints.

The young soldiers keep a grip on their rifles while one man searches the passengers and the vehicle.

Once in the town, it is the police who conduct random searches in the street.

New alliance?

Colombian authorities now regard criminal bands as the major threat

While the Bacrims fight for control of the lowlands, in the mountains, sitting on the coca fields, are the Marxist rebels of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) and the smaller National Liberation Army (ELN).

Just over a decade ago they were locked in a battle to the death with the paramilitaries of the AUC.

Now they happily sell coca base, which is then processed into cocaine, to the Bacrims.

The guerrillas are beginning to enter into agreements and even alliances with them, united by their common interest in the drug trade and in resisting the advance of the security forces.

"First it was just the purchase of coca base by the Bacrim," said Gen Alberto Mejia.

"Now the Bacrims pay in supplies, ammunition and weapons as well, and the rebels protect Bacrim leaders and even train some of their men."

The new chapter of Colombia's civil conflict has begun, with rebels, paramilitaries and drug cartels working together to traffic cocaine.

Much of the cocaine is now trafficked through Mexico, fuelling a violence there reminiscent of Colombia almost 20 years ago, when Pablo Escobar of the Medellin drug cartel took on the state, and almost won.