Peru prepares to elect new president

- Published

Peruvian presidential candidate Ollanta Humala has toned down his rhetoric since 2006

As voters prepare to go to the polls on 10 April, the BBC's Dan Collyns looks at the colourful personalities in Peru's presidential campaign.

Elections in Peru are notoriously unpredictable. Yet after a solid decade of peace, mainstream democracy and strong economic growth, it looked - just for a while - as if the 2011 presidential elections might be quite staid and, well, predictable.

Not a chance. In the past week, Ollanta Humala, the former army officer who came within six percentage points of winning the election in 2006, has leapt up in the polls with a clear lead over his rivals.

Five years ago, he was the foreign investors' bogeyman, viewed as Hugo Chavez's Peruvian poster-boy, who was poised to nationalise industries, re-write mining contracts and change the constitution to allow consecutive re-election.

But even his opponents cannot deny that he has toned down his rhetoric and is no longer the inexperienced firebrand of 2006, when he almost joined the "pink tide" of victories which saw Evo Morales become Bolivia's leader and Rafael Correa take office in Ecuador.

Firebrand re-branded

Now the one-time firebrand has swapped his red T-shirt for a suit which he sported on a visit to Lima's ultra-conservative archbishop, proclaiming to be a devout Roman Catholic.

But, with Peru's markets falling, investors are not totally convinced. This time around, Mr Humala says he will respect investors' rights but he does want mining companies to pay higher royalties and to change the constitution.

Several news reports say Mr Humala has advisers from the Brazilian Worker's Party of the popular former leader, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva.

"If our critics really looked at our proposals, they would see we are not a threat, in fact we would consolidate the Peruvian economy," Mr Humala told the BBC.

"But we want that growth to be inclusive... it is not reaching the poorest families.

"The few have too much, while the many have too little - that's what we have to change."

Implementing social programmes might be one of few reforms he would be able to make if he came to power, says Julio Cotler, a sociologist at the Institute for Peruvian Studies.

But his attempts to make more far-reaching reforms would likely be stymied.

"Both Chavez and Morales came to power riding a social movement that gave them the necessary legitimacy to make the transformations that they wanted," Mr Cotler said.

"If Humala makes it in, he will make it with 25% [support]."

His rivals, according to polls following a televised debate, are tightly clustered together as they vie for the second place in a run-off vote in June, which is the most likely scenario.

The former president, Alejandro Toledo, who until recently spent three months with a comfortable lead, is virtually neck-and-neck with Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of the former President, Alberto Fujimori, who was jailed in 2009 for human right crimes and corruption.

Nearly tied with them is Pedro Pablo Kuczynski - or PPK, as he is known - a former finance and prime minister during Mr Toledo's 2001-6 government.

Many Peruvians credit him with the administration's economic success and he is battling directly with Mr Toledo for votes.

'El Cholo'

Mr Toledo had waged a successful campaign before dropping from 27% to as low as 18.5% in polls. He cast himself as a leader who would keep Peru's China-like growth (averaging 7% over the last five years and driven by high commodity prices) while "re-drawing the social face" of the country, which has one of the biggest wealth gaps in the world.

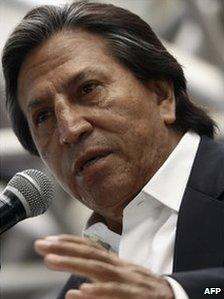

Candidate Alejandro Toledo, known as "El Cholo", was president of Peru from 2001 - 2006

He was born into extreme poverty, the eighth of 16 siblings, nine of whom did not live to become adults. He shined shoes as a child. A humanitarian worker couple helped him gain a scholarship to study in the US where he later gained a doctorate at Stanford University.

"I came out of deep poverty as a consequence of a statistical error," he told the BBC.

"The people of my country have the right to get out of poverty and the only way I know of, in the world, is through a good quality of education together with health care."

Mr Toledo can wisecrack with market traders and hold his own with investment bankers. He's the only candidate whose approval bridges all Peru's socio-economic strata, but he's lost ground to PPK in the upper-to-middle class band and to Mr Humala among the poor.

Keiko Fujimori is a polarising figure relying heavily on the groundbase of support for her jailed father, particularly among the urban and rural poor. She has the unwavering backing of one in five Peruvians trading on the surname which she admits "arouses great passions".

Equally, she faces a strong negative vote due to her father's authoritarian legacy and the strong suspicion not only that he's running her campaign from his cell in a Lima police base, but also that she would pardon him if elected.

Still rising, PPK, an Oxford-educated self-made millionaire, could also make the second round.

The former Lima mayor, Luis Castaneda, is trailing in fifth place in the polls, damaged by an audit which highlighted gross mis-spending during his mayoral term.

But with a third of voters undecided and political parties more fragmented than ever, there is still room for big changes.

Boom time

Growth in Lima is impressive; huge mega-malls spring up near shanty-town neighbourhoods and the ground throbs and whirs to the sound of high-rise construction.

The staple of any traffic jam, the tinny second-hand Japanese imports with a switched steering wheel known as "ticos", are fast being replaced by gleaming new SUVs.

But a third of Peruvians still live in poverty, a fifth of children are malnourished and one in five lack access to running water. The incumbent leader, Alan Garcia, prioritised public money for infrastructure rather than social programmes. Corruption is rife and crime is rising.

"In a moment when there's economic growth... when all the newspapers are saying it's the Peruvian miracle, the Peruvians aren't feeling the Peruvian miracle," says Julio Cotler.

- Published27 October 2010