Chile's HidroAysen dam project provokes mounting anger

- Published

Protesters say the dams will cause irreversible damage to this part of Patagonia

For the past few weeks, Chile has seen repeated and increasingly angry protests after regulators approved plans to build dams in the south of the country.

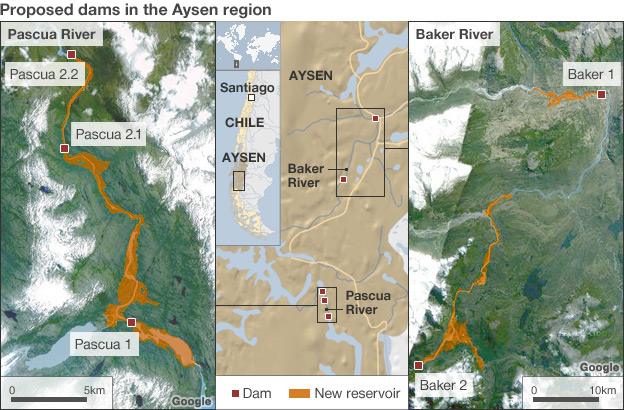

The project would see two rivers in the Aysen region of Patagonia dammed to provide hydroelectricity.

HidroAysen, the company in charge of the project, says the dams are an environmentally friendly, low-impact solution to the nation's growing hunger for energy.

Opponents, from conservationists to local farmers and scientists, argue that the dams will have dramatically negative effects on an important wilderness, as well as a vanishing way of life.

"HidroAysen didn't even consult with us; they showed up and gave us a relocation plan, as if they could kick us off our land before a decision was even made," says Lily Schindele, 39, who lives near one of the proposed dam sites with her husband and two children.

"Who has the right to decide the future of this region? A business that's located 2,000km (1,250 miles) away, or the people who live here?"

Getting to Mrs Schindele's isolated farm takes nearly two days of driving, bumping over dirt roads in a 4X4, cutting through dense cypress groves, over grassy plains and alongside dozens of waterfalls.

Once the dams are constructed, Mrs Schindele's farm, along with much of the surrounding rugged landscape, will be fully submerged at the bottom of a large artificial reservoir.

But Mrs Schindele is not just concerned about the loss of her property and home.

"These people don't understand these rivers or this region. This is one of the last wild places in Chile, and this project will change it forever," she says.

Locals fear their way of life will be destroyed

But Daniel Fernandez, the CEO of HidroAysen, says that the project is sustainable - and virtually unavoidable if Chile wants to meet its growing energy needs.

"The people who oppose the dams are people who don't share in the vision of development that Chile has adopted," says Mr Fernandez.

"They want conservation, but they don't take into account other citizens."

According to Mr Fernandez, by 2030 Chile will require three times as much energy as it does today.

He says the bulk of that new demand is due to home use, and public works projects, such as street lighting.

'Pristine places'

But Lily Schindele and others in the anti-dams movement say that the bulk of Chile's energy consumption is due to the country's vast copper mines in the northern Atacama Desert.

Environmentalist Juan Pablo Orrego has calculated that new mining projects will require approximately 12,000 additional megawatts of energy.

"Mining is the energy tension in Chile; without mining, there is no energy crisis," says Mr Orrego.

Scientists are concerned that dams will drastically alter the ecosystems of Patagonia, which oceanographer Giovanni Daneri says are unlike anything else on Earth.

"These are pristine places; some of them, no-one has ever even set foot there," he says.

The organisation Mr Daneri works for, Center for Research on Ecosystems of Patagonia, external, has calculated that Patagonia's fjords alone absorb the same amount of carbon dioxide that the entire country emits.

And those fjords are dependent on the health of the rivers that are now set to be dammed.

"What a dam does is it acts like a trap for sediment and nutrients," says Mr Daneri. "And the fundamental role of a river in an aquatic system is to move nutrients.

"The turbidity of the river is going to change, and we don't know how this is going to impact the ecosystem of the fjords."

Industry v conservation

Kris Tompkins, one of the founders of the Patagonia clothing line, now dedicates her time to conservation projects across the region, along with her husband, Douglas.

The Tompkins' vision of conservation rests on recognising the value of large protected areas, and supporting countries like Chile and Argentina as they build a culture of national parks and conservation.

Campaigners argue the region must be left as untouched as possible

"We're trying to elevate the importance and value of wild lands, and intact landscapes," says Mrs Tompkins, sitting in front of a large window looking out over the rolling grasslands and big open sky of what will be the future Patagonia National Park.

This is a 650,000-acre conservation project just a few hours from one of the proposed dam sites.

Yet Mrs Tompkins believes that conservation can only go so far, and that the Chilean government must better regulate industries like mining if the country is serious about protecting the environment.

"If 60% or 70% of energy is going to industry, then my mother can turn her lights out every time she leaves a room, but the fact is they need to keep building dams," says Mrs Tompkins.

"That's not because of my mother, but because of industrial growth, and because industry isn't being forced to be more efficient."

The government has insisted the country's energy sector needs to be expand to aid economic growth and lift thousands out of poverty.

Construction worker Carlos Hernandez, who lives in Aysen, believes the dams are necessary.

"Right now we generate power by burning petroleum and coal, which pollute the environment. We need these dams, and the electricity they'll generate. I just hope the project will give jobs to local people," Mr Hernandez said.

But Mrs Tompkins argues that the biggest problem with the HidroAysen project is not the construction but the drastic changes it will usher in.

"It's the discovery, effectively, of this region in terms of its natural resources. That's what will be the really cruel effects of the dams."

- Published10 May 2011