'I shot the cruellest dictator in the Americas'

- Published

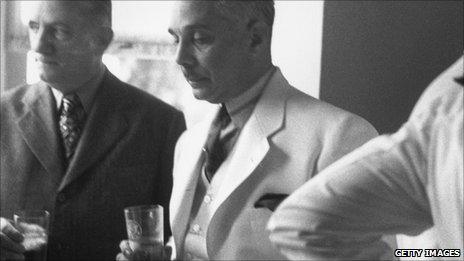

Rafael Trujillo's dictatorship is considered one of the bloodiest in the Americas

Before his assassination on a dark highway on 30 May 1961, the Dominican dictator, Rafael Trujillo, ruled with an iron fist for almost 30 years. Tim Mansel meets one of the men who shot him.

Rafael Trujillo's rule is considered one of the most brutal periods in the history of the Dominican Republic. Taking power in 1930, his hold over the country was absolute. He brooked no opposition.

Those who dared to oppose him were imprisoned, tortured and murdered. Their bodies often disappeared, rumoured to have been fed to the sharks.

In 1937, Trujillo ordered the racially motivated massacre of several thousand Haitians living in the country.

Gun battle

His rule ended when he was gunned down on 30 May 1961.

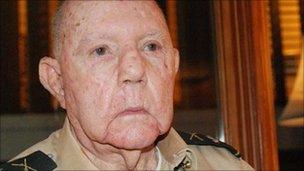

Gen Imbert went into hiding after the assassination

Antonio Imbert is 90. Fifty years ago he was one of the seven men who ambushed and killed Rafael Trujillo.

He is a large man with closely cropped hair and he has put on a military uniform for my visit.

General Imbert - he was given the military rank later to enable him to receive a state pension - is officially a national hero.

He is brought into the room by his wife, Giralda, moving slowly towards a small rocking chair. His wife lights a cigarette for him.

"What do you want to know?" he asks.

It was late evening when Trujillo was shot dead in a gun battle on the road that leads from the capital to San Cristobal, where the dictator kept a young mistress.

In their vehicle, Gen Imbert and three other conspirators were waiting for Trujillo's chauffeur-driven Chevrolet to come past. Gen Imbert was driving. Other gunmen were stationed further up the road.

The old man's memory is not what it was. But he does remember taking up the chase as Trujillo's car sped past and he recounts the first shots being fired.

He remembers Trujillo's driver slowing down and he has not forgotten the decision to pull across in front of Trujillo's car, blocking its path.

"Then we started shooting," he says.

Trujillo and his chauffeur were armed, and fought back.

Gen Imbert recounts how he and one of the others got out of the car to get closer to their target.

"Trujillo was wounded but he was still walking, so I shot him again," he says.

At the end of the gun battle, the dictator, commonly known simply as El Jefe, was left sprawled dead across the highway.

"Then we put him in the car and took him away," says Gen Imbert. They took his body to the house of a plotter, where it was eventually discovered by police.

'Salvation'

Fifty years later I wonder if he is happy to have shot the Dominican dictator?

"Sure," he replies. "Nobody told me to go and kill Trujillo. The only way to get rid of him was to kill him."

Gen Imbert is not alone in having drawn this conclusion.

In a letter to his State Department superior in October 1960, Henry Dearborn, de facto CIA station chief in the Dominican Republic, wrote: "If I were a Dominican, which thank heaven I am not," I would favour destroying Trujillo as being the first necessary step in the salvation of my country and I would regard this, in fact, as my Christian duty."

'Cordial relations'

During his rule, Trujillo collected medals and titles, and expropriated property and businesses for himself and his family. He renamed the capital city Ciudad Trujillo, and the country's highest mountain Pico Trujillo.

Throughout this, he maintained cordial relations with the US - a picture taken in 1955 shows him in smiling embrace with then US vice-president Richard Nixon.

But the relationship gradually soured over Trujillo's human rights record. The final straw was an assassination attempt sponsored by Trujillo, against the president of Venezuela, Romulo Betancourt. The US closed its embassy and withdrew its ambassador.

President Eisenhower had already approved a contingency plan to remove Trujillo if a suitable successor could be persuaded to take over. But the new Kennedy administration withdrew formal support for the attempt on Trujillo's life at the last minute.

The failed invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs had taken place the previous month, and President Kennedy was worried that a power vacuum in nearby Dominican Republic could allow another Castro to take power there.

"The Cold War had moved to the Caribbean," says Bernardo Vega, Dominican historian and former ambassador to Washington.

The only material support provided by the US for the assassination was three M1 carbines left in the US Consulate after the withdrawal of embassy staff, and handed over with CIA approval.

Within days of the assassination, Trujillo's son Ramfis took charge and almost everyone involved in the conspiracy and members of their extended families were rounded up.

Two of Gen Imbert's fellow conspirators were killed in gun battles while resisting arrest. The other four were imprisoned and later shot.

A plaque near the spot where Trujillo died commemorates their sacrifice. It refers to the killing not as assassination but as "ajusticiamiento", a Spanish word that implies justice being done.

"We Dominicans react very negatively when the people who killed Trujillo are called assassins," says Bernardo Vega.

"Ajusticiamiento is a way to give it a positive twist, to say that it was a good thing to do."

'Personal revenge'

Gen Imbert owes his survival to the courage of the Italian consul in Santo Domingo who allowed him to hide in his house for six months.

He still has one of the American M1 carbines, but he won't allow me to see it. "You don't show things like that," he says.

But he does let me see the hat he wore to disguise himself in the hectic days after the shooting.

He tells a story of how he took a public bus and the driver recognised him, but wouldn't take any payment out of respect for what he'd done.

And his wife brings out the pair of scuffed brown brogues that he was wearing the night he shot Trujillo.

They're surprisingly small - size seven-and-a-half - with worn patches on the soles.

"They've never been repaired," his wife tells me. "He puts them on every 30th of May and sometimes he wears them for several days."