Peru's challenge to tackle cocaine trade

- Published

On the front line of Peru's drugs war

Peru's Ene-Apurimac valley is the world's densest coca-producing belt but it is also home to some of the Andean nation's poorest people.

More than half the population live in poverty, yet the Andean-Amazonian valley, better known by its Spanish acronym as the VRAE, is a virtual drugs factory supplying Argentina, Brazil and Europe with high quality cocaine.

Coca farmers here no longer limit themselves to growing and harvesting their plantations.

They have branched out into processing the drug in hundreds of artisanal "cocaine kitchens" scattered throughout the valley.

Soldiers stationed in the VRAE say they have come across Olympic swimming-pool sized pits where piles of coca leaves drenched in a cocktail of chemicals are stamped on by villagers as if pressing grapes for wine.

Seizures

Most experts agree Peru's cocaine producers are now more efficient, getting more of the drug out of the raw material of coca.

This area can see up to five coca harvests in a year.

Soldiers are fighting "terrorism and trafficking", officers say

The UN's World Drug Report for 2011, external showed the VRAE's coca coverage increased by 13% in 2010 to 19,700 hectares (48,679 acres) - a third of Peru's total of 61,200 ha.

Peru's coca leaf coverage is practically on a par with Colombia's.

Overall, Colombia's coca coverage decreased by some 16% between 2009 and 2010, while Peru's rose by 2%.

And on some measurements, Peru is a bigger producer of coca leaf than its neighbour.

In both 2009 and 2010, Colombia seized 10 times more cocaine than Peru, according to the UNODC figures. Most analysts agree this suggests Peru is the biggest de facto exporter of the drug.

Some 4,500 military personnel are deployed throughout the VRAE, an area that straddles the Andes mountains and the Amazon jungle.

The soldiers' main mission is counter-insurgency to combat the estimated 500 Shining Path fighters who control much of the drugs trade.

The US state department has offered a reward of up to $5m , external for information leading to the capture of the rebels' leader in the VRAE, Victor Quispe Palomino.

Gen Luis Howell, chief of the Joint Command of the Peruvian Armed Forces, says they are combating "not just terrorism but also drug trafficking".

He acknowledges that they have made few gains but he says his men have pacified the area and kept the rebels away from population centres.

But the security operation has come at a price. Some 60 police and army officers have been killed in the past three years but no important Shining Path leader has been captured or killed.

Ruben Vargas, a Peruvian security expert, says both the military operation and attempts to bring economic development and basic services to the VRAE have failed.

"In the VRAE - which is the principal cocaine-processing laboratory in Peru - many villages don't have drinking water or electricity, the schools don't have teachers, the clinics don't have medical supplies and the powers-that-be are the Shining Path and the drugs trade. What kind of state presence is that?" asks Mr Vargas.

Lucrative journey

The predominance of the narco-economy drives many young men to join the army of "mochileros", or backpackers.

Each carrying between 10kg to 20kg of unrefined cocaine in their packs, they march in columns out of the valley and into the Andes.

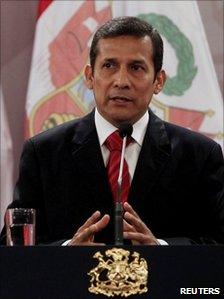

President-elect Ollanta Humala: Tackling the drugs trade is a key task

Choosing the most remote routes and protected by Shining Path rebels, they trek for several days until they reach a staging point where the drugs are bought.

They can earn up to $500 (£313) a trip, a small fortune in VRAE.

"Which would you rather be - a soldier or backpacker?" jokes army Gen Leonardo Longa.

Peruvians still tend to run the drugs trade in the country's interior, but security experts say that Mexican drug gangs, particularly the Sinaloa cartel, have displaced Colombian drug lords in Peru's coastal cities.

In recent years, there have been several drug-related killings, mainly of Colombians.

The murders caused alarm because they were unusual.

Gustavo Gorriti, an investigative journalist who focuses on security and corruption, believes organised crime could "quickly get out of control".

"When it reaches a certain level it's so much harder to eradicate. Mexico has a mid to high-level insurgency - it's a for-profit, capitalist insurgency but an insurgency nonetheless," he says.

Mr Vargas believes that if and when the Peruvian authorities decide to really tackle drug trafficking, this will mean more seizures of cocaine.

That in turn will trigger a response from the traffickers, he says, and "that is when we will see a rise in the levels of narco-violence".

The incoming government of President-elect Ollanta Humala may well face key decisions.

Mr Humala's election manifesto spoke of decriminalising coca farmers and even the low-level cocaine processors and smugglers.

Mr Gorriti believes that would be a positive step away from the "repressive" policy of the US-led counter-narcotics efforts, which he says criminalises much of the population in the VRAE.

Mr Vargas, however, says being too lenient with those involved in the drugs trade would be "naive".

The real concern is that if Peru's increasing cocaine production is accompanied by a spike in organised crime and the presence of Mexican cartels, the small coca farmers and small-time producers would be the least of the administration's worries.

- Published23 June 2011

- Published8 June 2011

- Published15 December 2010

- Published23 June 2010

- Published16 June 2010