Argentine trauma as top club River Plate relegated

- Published

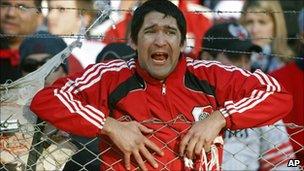

Disbelief to dismay: Pavone's penalty miss helped to seal River's fate

When a football club as big and successful as River Plate falls, it falls very hard.

And for a club as big and prestigious as this one, relegation to the Argentine second division for the first time in its 110-year history is about as serious and humiliating as it can be.

River Plate is an institution and most Argentines believe it belongs in the top division.

Even their arch rivals, Boca Juniors, when they have finished gloating, will want the club back for the twice-yearly clash between the two teams, the superclasico - one of the biggest, most exciting and lucrative matches on the world football calendar.

The post-mortem into where it has all gone so terribly wrong for River Plate began almost immediately.

That was even before the broken glass had been swept up and the stadium repairs carried out after fans rioted following the 1-1 draw against Belgrano that condemned their club to relegation.

This fan's agony was shared by many in the stadium and beyond

There are likely to be wholesale personnel changes as the club adapts to its reduced status.

The club president and former player Daniel Passarella has said he will stay on, despite calls for his resignation.

"They'll have to carry me out, feet first," he said.

"I never thought this could happen"; "The saddest day of my life"; "I'm in mourning forever," are just some of the many comments posted on River fans' websites.

Others have had to be removed for their insulting content.

Money worries

The players have simply said they will be back.

But escaping from 'La B', as the Argentine second division is called, will not be easy.

Firstly, the club's television money will be reduced from 28m pesos ($6.8m, £4,2m) a year, to 4m pesos.

It will have to lower entrance fees and will lose revenue because, as a result of crowd violence, away fans are not allowed in the second division.

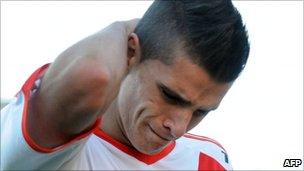

Young star Erik Lamela: Will he join the long exodus of River players?

Then the value of its squad will be diminished.

Argentine clubs survive and thrive by selling their best players abroad, to Europe and the rest of Latin America.

More than 1,000 Argentine players ply their trade at foreign clubs. But few foreign scouts look for potential talent in the lower Argentine divisions.

Football analysts and fans blame the regular sale of their best players abroad for what they see as a decline in standards across the Argentine league.

It has created a parity that has allowed the smaller clubs a look in and broken the dominance of the big two teams, River Plate and Boca Juniors.

The league in Argentina is designed so that the big clubs should not go down.

Relegation is determined by the average number of points accumulated over three years, which previously allowed those with the money to buy better players and move away from the danger zone. But the better players are now not available.

While the Argentine league as a whole has been suffering, River have had their own specific problems that reduced them to a consistently poor team over the past few years.

They have had five managers in the past three years and a change at the top when Daniel Passarella took over as president from the previous, much criticised top man, Jose Maria Aguilar.

The fans questioned the sale of some of the better players, and threw their hands up in exasperation at the purchase of some of their replacements.

Anti-depressants

Many clubs in Argentina suffer from the excesses of their hard-core fans or barra brava, but perhaps none more so than River Plate.

They have attacked their own stadium, damaged players' cars and some of their leaders are in prison awaiting trial on charges that they killed a rival gang member.

Yet River still had the chance to save themselves with a two-leg play-off against aspiring but humble Belgrano from the second division.

Fans' anger at the club's management had been building ahead of Sunday's defeat

River Plate's rivals call them Las Gallinas or the chickens for their failure to win crucial games in the past.

They were true to that sobriquet, losing 2-0 in the first leg and only managing that draw in their own stadium, missing a penalty into the bargain.

Psychiatrists have spoken about the impact that firstly the tension of the battle against relegation and then the misery of the drop may have on River fans, not accustomed to failure of this magnitude.

They report an increase in the number of calls to help-lines and the demand for anti-depressant drugs.

Sports psychologist Marcelo Roffe wrote in the La Nacion newspaper: "There's a state of intense grief among the fans about the team going down since River Plate is the Argentine side that's won most titles and what's happening just doesn't sink in."

Some say football is just a game. But the television pictures of hundreds of grown men reduced to tears and the scenes of violence and frustration after the game testify that in Argentina, at least to River Plate fans, it's much more than that.

- Published27 June 2011