Why Chile is an astronomer's paradise

- Published

Inside one of the telescopes and the control room at Paranal observatory

With its crystal clear skies and bone dry air, the Atacama Desert in northern Chile has long drawn astronomers. Some of the most powerful telescopes in the world are housed here.

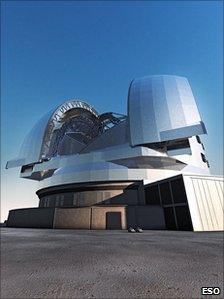

But now, work is about to begin on a telescope that will dwarf them all - not a VLT (Very Large Telescope) but an ELT (Extremely Large Telescope).

It will be built 2,600m (8.530ft) up in the Andes on a site overlooking the Paranal observatory, and when it is finished in 10 years' time it will be the most powerful optical instrument in the world.

The telescope will be the size of a football stadium, cost around $1.5bn (£930m) and weigh over 5,000 tonnes.

It will be built to withstand major earthquakes, a serious consideration in Chile.

Jigsaw puzzle

Astronomers say the images it produces will be 15 times sharper than those sent to earth by the Hubble space telescope, and might eventually help us find signs of life on other planets.

Construction of the E-ELT is taking precision engineering

The European Southern Observatory (ESO), external, which operates Paranal, says the telescope, and others like it, "may eventually revolutionise our perception of the universe as much as Galileo's telescope did".

The telescope's main mirror will be 42m wide. That is five times bigger than the mirrors on the existing telescopes at Paranal, which are already among the biggest in the world.

Because it is impossible to make such a large, curved, high-precision mirror, engineers in Europe will make nearly 1,000 small hexagonal mirrors which will be shipped to Chile and fitted together like pieces in a giant jigsaw puzzle.

Henri Boffin, a senior astronomer at Paranal, says the new telescope should help scientists address questions raised by the existing instruments at the observatory.

"What we have been able to do so far is raise a set of questions," Mr Boffin said. "Like, for example, we have discovered that the expansion of the universe is accelerating, but we have no clue why.

"There's a kind of dark energy we think is there, but we have no clue at all what it is. Similarly, we know that the universe is made in part of dark matter, but we have absolutely no clue what it is, and it makes up more than 25% of the universe.

"The new telescope will hopefully help us answer these questions."

The construction of the telescope is not the only major astronomical project in Chile.

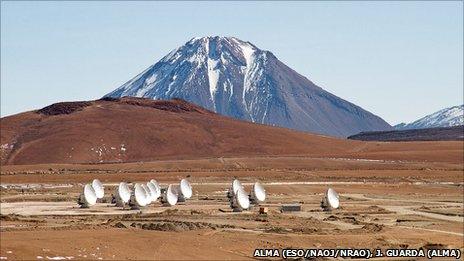

Just up the road from Paranal, engineers are completing the construction of ALMA,, external the world's biggest network of radio telescopes.

The ALMA telescopes have a key role in unlocking the universe's secrets

It will consist of more than 60 giant radio dishes, assembled on the Chajnantor plateau at a dizzying altitude of 5,000m.

Tim de Zeeuw, the head of ESO, says ALMA, which is scheduled to begin operations later this year, promises to be "as transformational for science as the Hubble space telescope".

Desert dry

These two projects are cementing Chile's reputation as an astronomer's paradise. By some calculations, by 2025 the country will be home to more than half the image-capturing capacity in the world.

Much of the reason for that lies in the desert skies, which are among the clearest on earth. In some parts of the Atacama Desert, rainfall has never been recorded.

Altitude is also important, particularly for ALMA. Radio telescopes pick up wavelengths from outer space, but the signals are often distorted by water vapour in the earth's atmosphere.

By building at altitude, in dry air, engineers can get above some of that moisture.

The telescopes in Chile have captured amazing information about the skies

But there are other reasons why astronomers are flocking to Chile.

Being in the southern hemisphere, its observatories are not in direct competition with those in the United States and Europe, which gaze out at different skies.

"If you want to do modern astronomy and you want to do it in the southern hemisphere, you have to do it in Chile," Mr Boffin says.

Politics and infrastructure are also factors. Chile has emerged as one of the most stable, prosperous countries in the region since its return to democracy in 1990. That stability is essential for long-term investment projects like these.

The existing telescopes at Paranal have already helped scientists make some remarkable discoveries.

For example, they captured the first ever images of a planet outside our own solar system, and helped astronomers work out the age of the oldest known star in the Milky Way - it is 13.2bn years old.

One of the observatory's greatest feats was proving that a huge black hole lies at the centre of the Milky Way.

Scientists calculate that this mysterious void has a mass three million times larger than the Sun.

The astronomers at Paranal are proud of these achievements but say they now want more.

And they say their giant new telescope will help them achieve it, taking our understanding of the universe to the next level.

- Published1 June 2011

- Published20 October 2010

- Published5 January 2011