Colombia: conflict zone where medical treatment is a rare luxury

- Published

The doctors and nurses treat more than 100 patients a day

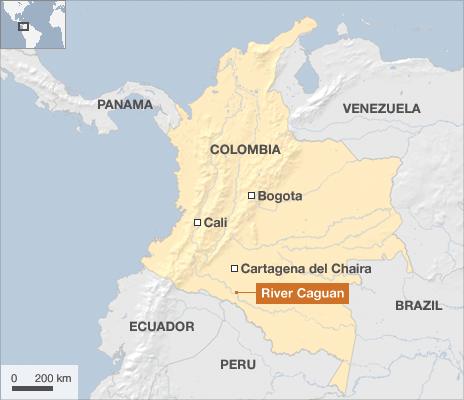

Healthcare along Colombia's River Caguan is a luxury.

Once you leave the town of Cartagena del Chaira and travel 600km (370 miles) south to El Guamo, there is not a single hospital, clinic, or doctor.

This is a region that has been blighted for 47 years by Colombia's civil conflict. Rebels from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) are still very active here.

The Caguan region was also, until the US-backed Plan Colombia , externalbegan coca eradication a decade ago, a centre for coca growing, and thus for the illegal drugs trade.

Now, the Colombian army is gradually pushing down the river and setting up checkpoints. Locals say the troops are displacing communities and causing much resentment.

The area is so tense that doctors from Colombia's own health service are extremely reluctant to work here.

In Cartagena del Chaira's one small hospital, Dr Alexander Reyes typically works 18-hour days, treating patients from the town and nearby communities.

But never does he venture further down the river.

"The distances are huge," he explains, "and the river is a dangerous zone."

Ordered back

Dr Reyes has personal experience of this region's dangers.

Four years ago he and a team of Colombian health workers set off down the Caguan, hoping to visit remote communities and offer medical care.

"We were stopped by the Farc," he says, "who asked what we were doing, they told us we had no permission to be there.

"They held us for several hours, then told us to get out and not to try to come back again."

Dr Reyes admits he was traumatised by the experience, fearing he could be held hostage for years.

More recently, another medical team was kidnapped for a week, and three years ago a doctor was shot dead - the rebels alleged he had stolen money.

While local medical staff cannot go down the river to treat patients because rebel forces won't allow them, people in need of medical care find it very difficult to get up the river to Cartagena.

There is no public transport, and private boats charge very high prices, partly because the Colombian army has rationed the supply of fuel into the region, saying it is used in the production of cocaine.

Four month check-up

In the absence of health services, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is providing medical care to the communities along the river.

Travelling along the River Caguan with ICRC delegate Abdi Ismail

"We try to go once every four months," says ICRC delegate Abdi Ismail, "with a team of two doctors, nurses, and a dentist.

"But this is a conflict area, and our access is dependant on the approval of the armed groups here."

The ICRC, which is drawing attentin to how health care is seriously hampered in conflict zones, , external has to negotiate with the Colombian army and the Farc to get approval for a trip.

The names and details of each team member have to be submitted to both sides, and approved by both sides.

It is a long and painstaking process, and each trip risks being cancelled if either side raises an objection.

When approval is finally granted, the long boat journey down the river begins.

Juan was able to get relatively prompt medical treatment

All along the route people are waiting.

One young man stands on the river bank and shouts for help; his wife is pregnant, and ill with what the ICRC nurse determines is pre-eclampsia, a serious condition which needs immediate treatment if she and her baby are to be saved.

Further down the river, 17-year-old Juan has sliced open his foot on an old oil can; the two huge cuts require 30 stitches, and Juan will be unable to walk for some time.

His only good fortune: the fact that the accident happened the same day the ICRC team was in his area.

In the village of Santo Domingo, the ICRC sets up its clinic in the long abandoned health centre - a dilapidated three-room building with broken windows, and, like the rest of the village, no electricity.

People have gathered long before the clinic actually opens, some have come from outlying communities, and have walked for hours to be here.

Among them are Sandra and her husband, Ovidio, a young couple with three children. Carrying their seven-month-old baby, who is ill with diarrhoea, they set off from home early in the morning.

"I worry a lot about the children, all the time actually," says Sandra. "In our village we have absolutely nothing. If one of my children were to have an accident the only thing I can do is ask God for help."

"There is no government here," Ovidio adds, "I think the government just doesn't care about us."

That sentiment is a common refrain among the local people. Many feel they have been abandoned by Colombia's government as a form of punishment for living in a region long dominated by the Farc.

Hoping for the best

ICRC doctor Francisco Ortiz, who typically sees more than 100 patients a day during the river trips, says many of the conditions he sees should be minor, but rapidly become serious, even life-threatening, because they are not treated soon enough.

"I really worry a lot about the people here," he says.

"It's so difficult for them to see a doctor, they only see one when we come. And so many of them have conditions which are preventable, or which we could treat if we saw them in time."

One such example is 44-year-old Mercedes, a mother of four children.

The last time the ICRC team visited she was given a routine test for cervical cancer. Today, four crucial months later, is the first time Dr Ortiz is able to tell her it is positive.

Now she must get the money together for the trip up the river to hospital, and her children must prepare for a long period without her.

The ICRC will help her with her travel costs, but it may not be enough, and her treatment may not be in time.

This seven-month-old baby needed treatment for pneumonia

"Crying about it won't get me anywhere," she says when she is told the news. "I can't do anything about it, I will just have to be calm and patient."

The situation of women like Mercedes is one of the reasons the ICRC has launched its campaign to remind warring parties that health and health services must be protected, and medical staff allowed proper access to all those in need.

But for the people of the Caguan River region, health is a right they have long given up on.

"What I hear over and over from the people here," says Abdi Ismail, "is that they simply have no right to get sick, it's not an option they are allowed to have."

And when the ICRC team packs up its medical equipment and travels back up the river, those left on shore know they will not see a doctor again for four months.

Anyone who is ill will simply have to wait, and hope.

- Published10 August 2011