Colombia's long task to identify conflict victims

- Published

Imogen Foulkes has been meeting some of the families of the missing

Colombia is home to one of the world's longest running internal conflicts.

For 47 years, government forces, rebel groups, paramilitaries and drug cartels have battled for control of large parts of the country.

Atrocities have been committed by all sides, and tens of thousands of people have simply disappeared.

Now, although the conflict continues, the Colombian authorities are beginning the work to find out what happened to those missing, to identify bodies found in mass graves, and to let families know.

To date, some 10,000 people have been identified but the process can be painfully slow, and many families may never get an answer.

Thousands missing

Sandra has not seen her husband, Francisco, for almost three years and does not know whether she is still a wife, or a widow.

She does not know whether her 10-year-old son, Brian, will ever see his father again.

A soldier in the Colombian army, Francisco came home on leave in October 2008, and went missing shortly after he returned to his unit.

Sandra's case is just one of the many with which the ICRC's Guilhem Ravier (right) is dealing

Sandra believes he may have been taken hostage by rebel forces, but she has no hard proof of that, and the army either cannot, or will not, provide her with any firm information.

"I'm living in complete uncertainty," she says. "I hope he is alive and well somewhere but I just don't know."

Sandra is being assisted by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in her quest for information, but her case is just one of many with which ICRC official Guilhem Ravier is dealing.

"There are 57,000 people officially registered as missing in Colombia," he explains.

"But we estimate the real figure is much higher.

"Countless persons went missing because of the conflict over the past decades. Many families, thousands, tens of thousands are still looking for them."

In her modest apartment in Bogota, Sandra tries to offer normal family life to Brian, but she admits it is difficult.

"He and his father were very close," she says. "When Francisco was away they used to talk on the phone every day. He's been very badly affected since my husband disappeared - going to school has become very difficult for him."

Across the city, in two dark rooms at the back of a garage Patricia and six-year-old Carlos (their names have been changed to protect their identity) are waiting for news, too.

Patricia is from the countryside, and she and her missing husband were once farm workers.

One evening four years ago he did not come home, and Patricia soon heard, unofficially, that he had been killed at an army checkpoint.

Inquiries to the army at first brought no result, then eventually Patricia was shown a picture of what looked like her husband's dead body, but wearing the uniform of a guerrilla from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc).

"I couldn't understand it, because he was never involved in anything like that," she says.

No grave

Patricia believes her husband was a victim of what has become known in Colombia as the "false positives" scandal.

Members of the security forces are believed to have killed hundreds, if not thousands, of young men from poor urban and rural areas. The victims were then dressed in Farc uniforms in order to falsely inflate the success rate against the guerrillas.

Dozens of soldiers have so far been prosecuted over the killings and several senior officers sacked for their alleged involvement.

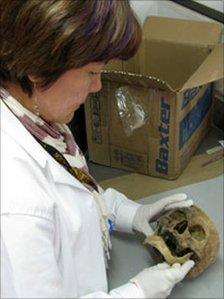

The aim is to put a name to the remains - and help families grieve

But independent witnesses to what really happened to Patricia's husband are, she says, too frightened to come forward. The army has so far denied her any further information, and refused her request for her husband's body.

"Since they told me he was dead I have begun to accept it," she says. "But I have no grave to go to, nowhere to put flowers. So I am still looking for him, it has no end."

For many women like Sandra and Patricia, the search for a missing husband will be long, and may not end with good news.

Groups who have renounced conflict in Colombia are gradually revealing the sites of mass graves and, at Bogota's national institute of forensic medicine, staff are working round the clock on the grim process of identifying the bodies being brought in.

Outside the institute, families clutching documents wait for news; inside, bodies - or fragments of bodies - are painstakingly being analysed. There is an overwhelming smell of death.

"The work is immense," says Carlos Eduardo Moreno, the institute's director.

"Because of the conflict, the violence in our country, the number of registered missing is growing every day, and we are getting more unidentified bodies every day as well - we are working round the clock."

The institute has recently acquired new equipment, which will speed up fingerprint and DNA analysis and hopefully deliver information faster to families, but even this will not mean that every family gets a definitive answer.

"Some families will never obtain an answer," says Mr Ravier. "We know that many bodies were really disappeared and will never be recovered. "

In the meantime, for Sandra and Patricia and their sons, the wait goes on.

"It's so hard," says Patricia. "With my husband I had a proper family for the first time in my life, we were happy. Now Carlos asks all the time where his father is, why he doesn't have a father like the other children."

"If I could just talk to him," says Sandra, "I would tell him how much I love him - he was my friend as well as my husband, we were together through good times and bad. I would do anything to get him back.

"I hope he's alive," she says. "But even if he's dead I want him back."

- Published19 July 2011

- Published6 July 2011

- Published26 May 2011

- Published27 May 2013

- Published18 September 2010