Will crime crackdown transform Rio's shantytowns?

- Published

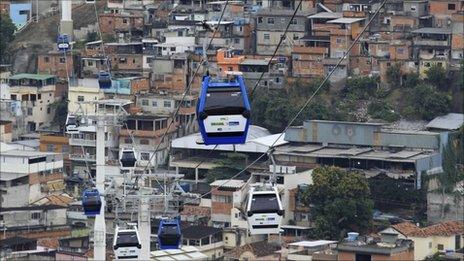

Rio's favelas are seeing increased increased investment but more is needed

As Brazil prepares to host the 2014 World Cup and the Olympic Games two years later, attention is not only on the progress of its stadiums but how well authorities are tackling high levels of crime.

In Rio de Janeiro, a policy of police occupation of the city's slums, or favelas, aimed at expelling the heavily armed drug traffickers who previously dominated them, is changing the face of the city.

The Unidades de Policia Pacificadora (UPP, or Pacifying Police Units) started in 2008. They are now in 17 favelas with plans to increase their presence into another 23 by 2014.

The programme attracted a visit from President Obama earlier this year when he spent some time in Rio's City of God favela.

The UPPs are also being seen as a model that could be introduced in other parts of the world, including in some Central American countries blighted by drug violence.

While an advertising campaign in the city boasts of freeing residents from the tyranny of drug gangs and economically reviving these communities, there are still challenges ahead.

Many communities previously relied on the drug gangs for services from water to wireless internet, and critics have pointed out that the state has been slow to replace them.

"Security alone is not enough," said Rio's Security Secretary Jose Mariano Beltrame.

"Having a policeman with a rifle at the entrance to a favela will not make things safe if things are not working inside the community. It's time for social investments."

Residents of the City of God slum, pacified in 2009, recently complained to police about a growing number of drug traffickers despite the UPP.

Despite these problems, there is hope. Among slum residents initially suspicious of the police, the police themselves, and the city's six million dwellers at large, many are optimistic about the future.

One resident of Cantagalo shantytown said: '"I didn't want the police here but at least now children don't see men walking around with guns, covered in gold, and learn that dealing drugs is the only way to get a motorbike or a car."

The community of Borel, in the north zone of Rio and part of a favela complex that is home to 30,000 people, has had a UPP in place for a year.

Police Captain Bruno Amaral agreed that there was considerable resistance from the community initially.

"Before the UPP it was drug dealers versus police, with the community stuck in the middle. Their only experience of the police was of them coming into the community during a shoot-out, then leaving afterwards," he said.

"Some people supported the drug dealers because they provided services for them like water and cable TV.

"We worked at getting closer to young people especially, putting on parties, football games, regular ju jitsu classes etc."

He said police have not eradicated drug dealing entirely from the favela but have made sure the traffickers no longer rule.

The key to success is community involvement, police say

"The police arrived and stabilised the community, now the services need to arrive. We are making a new kind of society."

There has been criticism in some other communities about the behaviour of the authorities, notably when troops invaded the vast Complexo do Alemao favela last November.

Some residents made formal complaints of suffering violence or robberies at the hands of the police.

A police spokesperson said those who break the law are punished.

"Misconducts are a reality inside any complex organisation," the official said. "The important fact here is that the UPPs are subject to the police's office of internal affairs and to the Civil Police when necessary, which means transparency is kept at all times."

There are four stages of the UPP process:

•Data and intelligence collected before an operation

•Special forces, known as BOPE, enter and occupy the land, driving the drug dealers out

•The UPP then installed inside the favela

•Finally, evaluation where community leaders, the police and other interested parties including NGOs meet up regularly to discuss progress.

A law is currently passing through Congress to ensure the UPPs stay for a minimum of 25 years.

The question is whether improved security can be maintained

Police officers say they will stay for as long as necessary - and in some areas that could be longer than 25 years.

Private investors, under Rio's industry federation Firjan, are contributing to projects including medical provision, education and work to boost the economy.

Angelo Campos, a resident of Complexo do Alemao, patrolled by rifle-carrying soldiers since November, highlights the need for more than just law enforcement or cash injections.

"We're not animals and it's not enough just to give money," he says.

"Many of the projects are not sustainable enough to work. A lot of the social projects promised by the government still haven't arrived here at all.

"We now have cable cars in one part of the community for access, but some people lost their homes and had to be re-housed to make way for those."

Having worked in various low-paid jobs such as a hospital porter, nowadays Angelo is a graffiti, T-shirt and sign artist.

But he says it is still very difficult for people from his community to achieve their goals.

"People in the favela don't believe in themselves. What is really needed in the long term is more education."

- Published20 June 2011

- Published1 July 2011

- Published29 November 2010

- Published5 March 2012