Protecting Peru's ancient past

- Published

Skeleton of a young man found at Machu Picchu

The return to Peru of the bones of 177 people taken a century ago from the Inca city of Machu Picchu has marked another important milestone in the repatriation of Peruvian antiquities.

The country is the birthplace of many ancient civilisations.

The most famous, the Incas, ruled the area for centuries until the arrival of the Spanish colonisers in the 1500s.

Every year, more than a million visitors marvel at the site which has become synonymous with Inca culture: the ancient city of Machu Picchu.

Perched high on a mountain top in the Andes, it is Peru's most important tourist destination.

But the almost 50,000 pieces found there between 1911 and 1915 had not been seen in Peru until recently.

Slow return

They had been housed at Yale University in the United States.

The university is only now beginning to return them, after Peru waged a long diplomatic and legal campaign to recover the artefacts, which it said had only been loaned to Yale.

In March, Yale shipped a large number of ceramics taken from the site back to Peru.

It is a move some had come to doubt would happen. One of them is Blanca Alba, who is in charge of repatriations at Peru's ministry of culture.

"I never thought I would see the return of the pieces," she says, her eyes getting teary as she remembers the arrival of the ceramics nine months ago.

"There were people waiting at the airport, they began singing the national anthem, I cried because it was very emotional."

Some of the ceramics are now being shown at a temporary exhibition space in Cuzco, while a new museum is being built to house the pieces once their return is complete.

Costly repatriations

But despite the satisfaction of bringing back the antiquities, Ms Alba believes it would be more cost-effective if the government prevented archaeological treasures from leaving the country in the first place.

"The problem is that repatriations are expensive," she says.

"They involve a court case, and you need to pay lawyers, transportation, packing, insurance, laboratory tests, etc," she explains.

In 2007, the Peruvian government estimated that it spent $625,000 (£400,000) on the repatriation of some 400 antiquities.

Ms Alba believes repatriating antiquities is, in the long term, a price worth paying, but she would prefer it if more was done to fight looting.

Preventing looting

The Peruvian government estimates that there are around 100,000 archaeological sites in Peru, of which only little more than a 10th have been uncovered.

When they do come to public notice, it is often because treasure hunters and professional looters have already been there.

People who are caught looting can expect a jail sentence of up to eight years.

But Director of Archaeology at the Peruvian ministry of culture Luis Caceres believes this is not enough.

"The reality is that, because of lack of funds and resources, we can't defend our heritage," he says.

He says it is impossible to provide security at all of the archaeological sites, especially with police busy fighting street crime.

Satellite technology

Mr Caceres admits the task is made more difficult by the fact that many sites are still undiscovered.

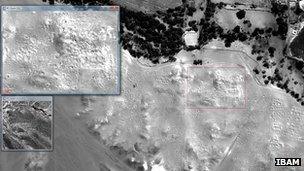

Experts say satellite images such as this one can show where looting has taken place

But he is encouraged by successes in Guatemala, where ancient ruins were found in the jungle using satellite imagery.

The technology allows archaeologists to see what is not always visible on aerial photographs, or what is hidden under layers of dirt and rock, or under a dense tree canopy.

Nicola Masini of Italy's Institute for Archaeological and Monumental Heritage has been using satellite imagery in Peru since 2007.

He says there are many advantages.

"Most archaeological sites in Peru are located in areas that have difficult accessibility, in the desert or the highlands, where it's difficult to do direct surveillance or aerial surveillance."

Mr Masini believes satellites could also be used to combat looting, because they reveal the presence of fresh excavations.

"The only way to monitor and manage this problem is with satellite data," he says.

'Losing history'

"It would be useful to the Peruvian authorities, so they can put adequate strategies in place for the protection of these remote archaeological sites," he adds.

Mr Caceres at the ministry of culture in Lima welcomes the use of this technology, despite its potentially high cost.

But he thinks satellite imagery should not be the only weapon in Peru's arsenal.

He would like to see public campaigns being launched to show rural communities that, in the long run, they could profit more from sites which are carefully managed by archaeologists.

He argues that those sites are likely to attract more tourists than those that have been looted, bringing badly needed cash to remote communities.

What is at stake, he says, is Peru's heritage, "because if an artefact leaves the country," he concludes, "with it, we are forever losing our history."

- Published31 March 2011

- Published12 February 2011

- Published21 November 2010