Mexico's drugs war: Lessons and challenges

- Published

Troops have been deployed in different Mexican states since late 2006

For the past five years, Mexico has been engaged in a bloody confrontation with drug gangs. Mexican political scientist Eduardo Guerrero Gutierrez looks at how the struggle is going and the implications for Mexico's presidential election in July.

The past year has been one of light and shade in the fight against organised crime in Mexico.

The violence of the drug cartels, against one another as well as against the security forces and innocent citizens, continues to dominate the headlines.

Five years after President Felipe Calderon launched his crackdown on the gangs, there have been some 50,000 drug-related killings.

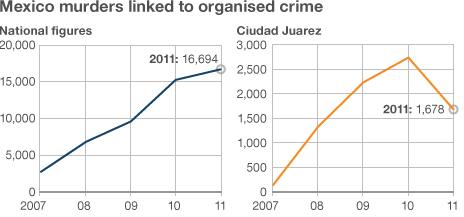

The number of murders in 2011, estimated at around 16,700, is 9% up on the total for 2010.

However, a more detailed analysis suggests that the level of violence has stabilised, especially given that from 2009 to 2010 killings jumped by 60%.

Indeed, the past year saw an improvement in some of the cities worst hit by organised crime.

The main example is Ciudad Juarez where killings in 2011 were down some 40% compared with 2010. Given these figures, it no longer seems justified, if it ever were, to call Juarez the world's most dangerous city.

2011 was marked by the increasing confrontation between two criminal gangs.

On the one side is the Pacific Cartel (also known as the Sinaloa cartel) headed by Joaquin Guzman Loera, El Chapo or Shorty. He is one of 11 Mexicans who are on the multimillionaires' list compiled by Forbes business magazine.

On the other are Los Zetas, originally the "armed wing" of the Gulf Cartel.

Extortion rackets

Given the federal government's success in dividing other drug gangs, the Pacific Cartel and Los Zetas appear to be the only organisations still able to mount large-scale drug-trafficking to the US market.

Troops are also trying to root out home-grown illegal drugs

The Pacific Cartel has what could be termed a more "business" profile, focusing in general terms on drug smuggling.

The Zetas, by contrast, have more of a military stamp (given that its founders include deserters from the Mexican army) and tend to be heavily involved in extortion rackets in the communities where they operate.

A key plank of President Calderon's security strategy has been tackling the organised crime gangs head-on, with the emphasis on arresting their leaders. This policy is likely to remain in place until the end of his administration in December 2012.

One positive development in 2011 was a greater effort to contain violence.

For example, resources have been concentrated on tackling Los Zetas (the most violent cartel), with a rapid and more effective deployment of troops and federal police in areas where violence surges.

This was seen in joint operations in Acapulco and Veracruz in October, and which in a few weeks managed to reduce killings considerably.

A perverse effect, however, of the strategy of arresting gang leaders and confronting the cartels has been the rise of mafias dedicated to extortion.

Some criminal cells, who belonged to now-defunct cartels, have recognised there is no space for them in the transnational drugs trade and have opted to focus on more local crimes.

Given the climate of conflict between cartels and the ineffectiveness of local authorities, people are more prepared to tolerate a gang that protects them in return for regular payments.

It could be that extortion already poses a greater public security problem in Mexico than drug-trafficking, at least from the viewpoint of Mexican citizens.

Although there are no reliable figures, statements from local people suggest that the "cobro de piso" (the protection payment) and reprisals against those who refuse to pay are systematic practices in various parts of the country.

Crime question

There has been a growing involvement of organised crime in local politics over the past five years.

Thirty-one mayors, former mayors and mayoral candidates have been killed, as well as the front-runner for governor of Tamaulipas, a northern border state that has seen some of the worst violence.

Felipe Calderon's term will actually end in December 2012

There may possibly be attacks or other high-profile actions designed to put on a show of force and intimidate candidates, the president-elect or the incoming government.

However, it is unlikely that the cartels would try to impose their choice of candidate in the July presidential election, or try to directly influence federal elections.

The main factor for this is that there are other interest groups with more resources and in a better position to influence national politics. These include the larger public sector trade unions, such as the teachers' union, or the telecommunication companies.

The parties' stance on security will be a central part of their campaigns - and their attacks on one another.

For example, President Calderon has already suggested that the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), whose presidential candidate is leading the polls, has members who wish to return to "past arrangements".

This refers to supposed pacts agreed with the PRI, which was in power from 1929 to 2000, that allowed some cartels to freely carry out their trafficking.

The PRI's candidate, Enrique Pena Nieto, roundly rejected such an accusation.

What is clear is that organised crime and the government's security policy will be major issues in the election - and beyond.

Translated from the original Spanish by Liz Throssell, BBC News