Cuban embargo at 50: US cars with Soviet parts

- Published

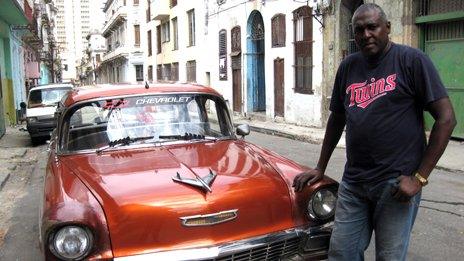

Jesus Campos runs his hybrid Russian Lada/US Chevrolet as a taxi

The US trade embargo with Cuba is 50 years old and Washington shows no sign of ending it. In Havana, the BBC's Sarah Rainsford asks how Cubans have learnt to adapt.

The classic American cars that crowd the streets of Cuba are a huge draw for foreign tourists. But for their owners, they're mostly a huge headache.

"It's not so much whether I like it," explains Jesus Campos, emerging from beneath the bonnet of a dusky-orange 1950s Chevrolet that has seen better days. "It's all I've got."

Keeping such cars running is testament to the Cubans' forced ingenuity.

Many Cubans complain the people suffer from the blockade

"There's a lot of Soviet parts in there," Mr Campos says, pointing out the pistons, water tank and much more - designed for a somewhat less stylish Lada or Volga.

"The originals are very hard to get, because they're American."

The US has now blocked all trade with Cuba for 50 years. The policy began at the height of the Cold War as Cuba aligned itself ever more closely with the USSR.

'People are suffering'

It remains today, explained as a form of pressure for democratic reform on this Communist-run island.

Havana is littered with reminders of a different time when American money flowed freely here. The towering Habana Libre was once the Hilton. On another street the New York Hotel is now a shell, windows shattered and walls crumbling.

The confiscation of US property by Cuba's revolutionary government was a key trigger for the embargo.

But five decades on little has changed politically on the island. It has just grown poorer.

"It's the people who are suffering from this blockade," Mr Campos says, voicing a common Cuban refrain. A former basketball player, he now runs his Lada-Chevrolet hybrid as a taxi.

"We have no access to decent things and what there is, is more expensive. But the people are not to blame for the politics," he argues.

The Cuban government says the US embargo has cost it $104bn (£65bn) so far. The policy - modified several times over the decades - bans trade, tourism, investment and even loans from organisations like the World Bank and IMF.

'Natural partner'

The embargo allows some exceptions for import of US food and medicine. But when the Spanish oil firm, Repsol, wanted to explore for oil in Cuban waters it had to bring a rig from China with less than 10% US-made parts.

The once glamorous New York Hotel is a shattered, crumbling shell

Distance drives up cost with everything.

"The US is the biggest economy in the world, 90 miles from Cuba," says Ricardo Torres, from the state-run Centre for the Study of the Cuban Economy.

"In normal conditions it would have been our natural partner."

Like many, he puts the embargo's endurance down to a powerful US lobby of Cuban-American emigrants - sworn enemies of the Castro brothers' regime.

"There have been many arguments to support the US policy, from Cuba's siding with the Soviets to human rights, but the US has relations with many countries with poor relations on human rights," Mr Torres says.

"Cubans are frustrated the US fails to change the policy, even though it's not producing what they're looking for."

Americans once imported 30m Cuban cigars a year

Instead, the Cuban government uses the embargo as proof of a policy of US aggression against the island - a national threat - and so justifies all kinds of restrictions.

Until the 1990s, the effects of the US policy on the Cuban economy were mitigated by vast subsidies from the Soviet Union. The collapse of the USSR and the subsequent loss of the subsidies had a devastating impact.

The country struggled through the "special period", as it was known, seeking new markets and new allies. Socialist Venezuela held out a crucial lifeline.

Since President Barack Obama entered the White House, the embargo has eased slightly. Cuban-Americans can now travel freely to the island and are no longer limited in the amount of money they can send back.

'It's fabulous'

It is also slightly simpler for American tourists to travel here directly now, though only on special licenses. Tourism has become a vital source of revenue for Cuba since the loss of its Soviet prop.

But now, "Cuban cigars are out of America," says Ana Lopez

"I've always wanted to come, and it's fabulous," says American tourist Barry Wolfe, who is on a guided tour of Old Havana. His trip was arranged legally, but the process was complex.

"It's a shame. I wish it would open up for free passing back and forth," says Mr Wolfe, who is from the state of Virginia, "but the politics are complicated."

He believes fellow Americans would "come flooding to Cuba" if restrictions were lifted.

Presumably, the hand-rolled cigars that once poured into the United States, 30 million a year, would be a key draw. Now, Europe and China are the key markets.

It's said that President John Kennedy ordered 1,000 of his own favourite 108mm smokes before imposing the trade embargo.

"I think he probably estimated the blockade would last one year, and three per day would be enough," says Ana Lopez, marketing director for Habanos cigars.

"Unfortunately it's lasted for 50 years already. And now Cuban cigars are out of America."