Obituary: Oscar Niemeyer

- Published

Niemeyer gave the world some of its most striking buildings

"You may like my buildings or you may not," Oscar Niemeyer often said, "but you'll never be able to say you've seen anything similar before."

And for many people who visit Brasilia, the capital city regarded as the Brazilian architect's masterpiece, that is undoubtedly true.

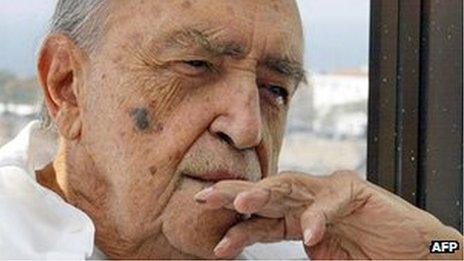

Oscar Niemeyer, who has died aged 104, was one of the most innovative and daring architects of the last 60 years.

Rejecting the cube shapes favoured by his modernist predecessors, Niemeyer built some of the world's most striking buildings - monumental, curving concrete and glass structures which almost defy description.

Conceived with a few curving lines on a sheet of paper, his designs are regarded by many as more sculpture than architecture.

Curved universe

Oscar Niemeyer was born into a financially comfortable family in Rio de Janeiro in 1907. As a young man he was something of a rogue - describing in his memoirs, The Curves of Time, his visits with friends to the local bars and brothels.

His love of the female form, and the curving mountains which hem Rio to the sea, were a great influence on the architect.

"Curves," he wrote, "make up the entire universe, the curved universe of Einstein."

In 1928 he married Annita Baldo - it was a marriage that lasted 76 years until she died in 2004.

The design of the National Cathedral in Brasilia leaves it awash with light

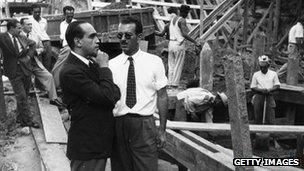

After graduating in the mid-1930s, he joined a Rio architectural firm run by a man who would become one of his great collaborators, Lucio Costa.

Having won wide praise for a number of buildings in Brazil, he was chosen in the early 1950s to be part of an international team given the task of designing the UN buildings in New York.

It was led by the great Swiss-born architect Le Corbusier, who was 20 years older than Niemeyer.

He praised the young Brazilian's work, but some commentators have suggested he was so nervous about Niemeyer's growing reputation that he prevented his designs from being selected for the project.

Unesco recognition

The work which is regarded as the most complete expression of Niemeyer's approach to architectural design is Brasilia - an entire city carved out of the Brazilian interior 700 miles from the beaches of Rio.

It was the brainchild of Juscelino Kubitschek de Oliveira, who was the Brazilian president between 1956 and 1961.

The Niteroi Contemporary Art Museum was completed in 1996

The project was highly ambitious but was officially inaugurated just four years after work was started in 1956.

Lucio Costa laid out the street plan in the shape of a bird or an aeroplane.

Niemeyer, his friend and colleague, then designed a huge number of the city's residential, commercial and government buildings.

They include the National Cathedral - a crown-shaped structure of glass suspended between concrete struts which sweep upwards and inwards and then reach out to the heavens. Rather than dark and forbidding like the interiors of older cathedrals, the inside is awash with light.

Many criticise Brasilia for being impersonal.

But 50 years on more than two million people live there and it is the only modern city to be named a Unesco World Heritage site.

Years of exile

Niemeyer was a life-long communist so when a military dictatorship came to power in Brazil in 1964, he was forced to move to France.

However, his work took him all over the world.

Niemeyer (left) designed buildings around the world - this site is in Rio in 1950

As well as building the Communist Party headquarters in Paris, his other commissions included a casino in Madeira and the University of Constantine in Algeria.

In the 1980s he returned to Rio - his true spiritual home.

One of his later buildings was the Niteroi Contemporary Art Museum which was completed in 1996.

Across the bay from Rio, it perches on a cliff-top - an upturned flying saucer, its curves reflected in a pool which encircles its central pillar.

He remarried when he was in his 90s and continued to work beyond the age of 100.

His most recent projects included a cultural centre for the town of Aviles in Asturias, Northern Spain and he also opened a museum of his work housing models and plans from his career.

Despite his passion for design he never believed architecture would change the world.

He accepted that great buildings were often the reserve of the rich - but he hoped that he could provide joy and amazement for ordinary people. In that, he must surely have succeeded.