Brazil's truth commission faces delicate task

- Published

The 1964 coup was bloodless but heralded two decades of military rule

Brazil's Truth Commission, created to investigate human rights abuses committed during the country's military dictatorship, is set to meet for the first time on Wednesday amid criticism from both army officers and victims' relatives.

Military rule spanned 21 years, from 1964 to 1985. More than 400 people were either killed or disappeared, while thousands were tortured.

As the commission gathers for the first time, there is discomfort among some in Brazil's military over what they perceive as an attempt at revenge by an ideologically-biased government.

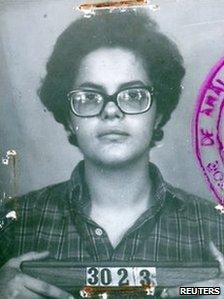

President Dilma Rousseff was herself arrested and tortured during the dictatorship.

"Of course there were terrible things that happened in this period but there were victims on both sides and they only want to tell one side of the story," says retired Vice Admiral Ricardo Antonio da Veiga Cabral, chairman of Rio de Janeiro's Navy Club.

Since the military are barred from publicly expressing their views or organising unions, their social clubs - headed by retired high-ranking officers - are useful gauges of the mood among the armed forces.

The Navy Club has designated seven of its members - "seven trusted officers", according to Vice Admiral Veiga Cabral - to form a "shadow commission" to counter whatever accusations may come their way.

But the victims of the regime and their relatives are not happy either, because the commission will have powers to investigate human rights violations but not to punish perpetrators.

Numbers vary, but official reports suggest that between 400 and 500 militants and civilians were killed by the military or simply disappeared.

Amnesty law

Memories of Brazilian military rule

"We wanted a 'Truth, Memory and Justice' Commission. With the resources and powers given to the commission I doubt very much they will be able to come up with anything groundbreaking," says Victoria Grabois, president of Rio de Janeiro-based organisation Tortura Nunca Mais (Torture Never Again).

Her father, Mauricio Grabois, a high-ranking Communist Party official, has been missing since 1973 when the army raided the guerrilla camp where he was based.

The Brazilian government acknowledged in 1995 that the state was responsible for killings, disappearances and torture during military rule, but a 1979 Amnesty Law - recently upheld in a Supreme Court ruling - prevents any prosecutions.

The recently appointed members of the commission are already making it clear that they, too, have neither the authority nor the intention to prosecute anybody.

Dilma Rousseff was jailed for three years

"We are not here to punish, that's not the job of any truth commission in the world," says commissioner Paulo Sergio Pinheiro, a Brazilian legal scholar who is also currently also the Chairman of UN's International Commission of Inquiry for Syria and former UN Special Rapporteur for Burma.

"There have been more then 40 truth commissions in the world since the 1980s and we will benefit a lot from their experience," Mr Pinheiro told BBC Brasil.

But the creation of the Brazilian Truth Commission has also highlighted the contrast with other Latin American countries - like Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay and Peru - which have already gone through this process, and where in some cases there have been prosecutions and convictions.

"It's fair to say that Brazil is late in respect to its Truth Commission but it's unfair to say that nothing has happened since Brazil returned to democracy in 1985," says Mr Pinheiro.

"Brazil has even paid compensation to relatives of people who went missing. I don't think any other country has done this."

Limited hope

The Truth Commission will have two years to conclude its work but it is not yet clear if it will be able to make public any of the confidential military documents its members will be allowed to view.

"I hope they will bring names and officially tell us who were people who committed those crimes but unfortunately I don't think this will happen.," says Mrs Grabois.

She says she has not given up on finding out more about her father, now missing for almost 40 years, but admits she has lost hope of overcoming the 1979 Amnesty Law in order to secure a prosecution.

"It's very hard. There have been some attempts to carry out prosecutions for kidnappings under common criminal law for but the courts have not yet accepted these either."

Vice Admiral Veiga Cabral says there is disquiet among veterans over the risk of prosecutions.

"This can grow like a snowball and we never know where it stops. An amnesty was granted for actions committed by both sides and that was an end to the matter."

But Mr Pinheiro does not accept the view that there are two sides to the issue.

"We have to make a complete, complex and honest investigation of the crimes that the state has already taken responsibility for. The side that matters is the side of the victims," he says.

While there is little expectation in Brazil that somebody will ever be actually punished for crimes committed during the dictatorship, the new investigation may at least bring some closure for relatives.

- Published14 March 2012

- Published27 October 2011

- Published27 October 2011