Rio 2016: The race is on to revamp Brazil's party city

- Published

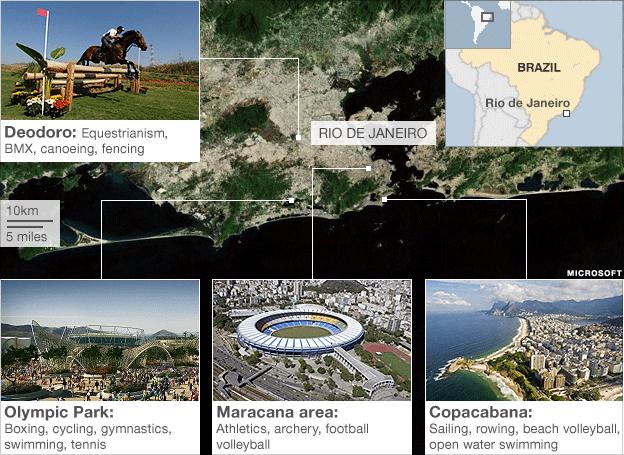

The curtain has fallen on the London Olympics, so all eyes are now turning to the next host city - Rio de Janeiro. Brazil has a huge task to get the venues ready, as the BBC's Quentin Sommerville reports from the city.

At the beach's edge in Barra da Tijuca in Rio de Janeiro, Brazilian kiteboarding champion Milla Ferreira wrestles in twisting winds, with the nine-metre long kite flying high above her head.

The waves are high, the wind changeable, but Ms Ferreira appears magnetically attached to her board, as the kite moves her at speed across the water.

In its Olympic debut, kiteboarding will replace windsurfing at Rio 2016.

"We are stoked," she says about the young sport's inclusion, which will be a chance for it to develop, even if it has its challenges.

"If God doesn't want to give the wind then you just go back to the house, there's nothing you can do," she explains.

Rio is taking a similar approach to its own Olympic debut.

The Games are being embraced as a chance for it to show the world its vigour, while allowing Rio to develop and improve.

That Olympic watchword - "legacy" - is on the lips of politicians throughout the city.

"It's not like we're going to be perfect by the end of the Games," says Eduardo Paes, the city's mayor and cheerleader-in-chief for what the Games can do for Rio.

Kitesurfing replaces windsurfing as an Olympic sport

"Brazil still has a long way to go, Rio still has a long way to go, but it is going to be a more equal, more just, more integrated city after the Games," he says.

"Bringing the Games here will mean the gathering of nations, of sports - what it always means - but it will mean lots change for a great country and a great city."

But not since the Games in Athens has a city faced so many questions about the ability to host the Olympics, and the World Cup, which kicks off two years earlier.

Speedy buses

Transport is one of the biggest headaches.

Rio's splendour, its soaring hilltops and winding coastal roads, make it a difficult place to get around.

It has more than six million people, yet only two metro lines.

The planned Olympic Park lies beyond reach of the metro and direct bus lines.

Quentin Sommerville has visited the operations centre for the next Olympic Games

The metro is being extended, but that requires blasting through a hillside of solid granite.

The completed tunnel will be nearly 6km (nearly four miles). But it is slow, laborious work and in two years, they have managed only 2km.

With the Olympic clock ticking, Rio does not have the time to build an extensive new metro system, or for that matter, the money.

So instead the city has bought dozens of new buses, which travel in exclusive lanes.

The first line on the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), the TransOeste corridor, is already open.

For some of the city's poorest residents, the BRT has cut their journey time to work by half.

Alexandre Sansao, the municipal secretary of transport, says the metro lines being built will be integrated with the BRT system. Currently 15% of people use the system.

"[By 2016] we will be able to transport 60% of the people in this high capacity system of transport," he says.

Slum anger

However, some of the most critical parts of the network will not be ready until just months before the Games begin.

The Maracana stadium, once the biggest in the world holding nearly 200,000 people for the 1950 World Cup, is undergoing a much-needed refurbishment for the 2014 World Cup.

It is also key for the Olympics, hosting the opening and closing ceremonies. But it, too, has had its problems.

Strikes have cost the project - where work goes on nearly 24 hours a day - 20 days of lost construction that it can ill afford.

The roof over the seating areas was found to be unsafe and had to be demolished, adding between 20% and 30% to the cost of construction.

And the city's existing velodrome, built for the 2007 Pan American Games, does not meet Olympic standards and may need significant upgrading.

The mayor insists that demolishing the structure is unacceptable, and that it will be fixed in plenty of time for the 2016 deadline.

Others are sceptical of promises that the Games will bring greater equality to the city.

The Maracana Stadium was once the biggest in the world, holding almost 200,000 people

The slum of Vila Autodromo is set for demolition to make way for the new Olympic Park.

"I believe that justice was made for all. We have all the rights to this land, we've been here more than 40 years, and we have the documentation to prove it," says Altair Guimaraes, a resident of the shanty town who delivers newspapers until 3am.

After he finishes work he continues on building improvements to the house he has lived in for 17 years.

He and his neighbours are fighting the Olympic planners every step of the way.

Mr Guimaraes insists that only property developers will benefit from much of the Olympic redevelopment and he does not want to be relocated.

In his yard he keeps chickens and grows pineapples, something that would be impossible in the apartment block the city wants to move him to.

Soon he is to meet the mayor to offer a proposal, developed with the help of professors from local universities, for the redevelopment of the slum that does not encroach on the Olympic plans.

"The Olympics don't have to mean the removal of anyone," he says.

"This is what the mayor should have done - tell those governments abroad that Brazil can do it differently. They don't have to do this to my community."

But with its annual carnival, Rio - the first city in South America to host the Games - knows how to throw a party.

On the beach at Ipanema, Ursala Araujo admits she has been worried about the city's infrastructure, but she has no doubt about the welcome Rio will provide.

"Have you never felt not welcome here? It will be just like now, it will be just a pleasure for us to have all you guys here from everywhere," she says.

However the pressure is now on Rio to convince the world that it will be ready for 2016.

And the city authorities must also assure residents that the huge costs of hosting the Games will benefit them long after the Olympic flag is lowered.

- Published29 February 2012

- Published28 May 2012