Nicaragua's jungle graveyard gives hints to future

- Published

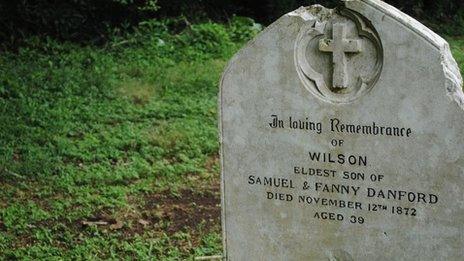

The graveyards of Greytown are a physical reminder of a long-gone era

Half-buried in the fringes of a thick jungle along Nicaragua's southern Caribbean coast, the remains of a once promising British colonial outpost hide shyly from the rest of the world.

Greytown, as the British called this river-mouth trading post in the 18th and 19th Centuries, is now a quintessential ghost town.

Peter Stevenson was drawn to Greytown to find out more about his family's history

There are far more graves than living souls here. A rusting iron fence marks out four cemeteries: British, Catholic, Masonic and Sabine, the last named after a US frigate that lost eight crew and officers here the mid-19th Century.

The last residents of this former British protectorate (1748 -1860) were relocated a few kilometres upriver in 1984, after a firefight between Sandinista soldiers and Contra rebels burned the town to the jungle floor.

Today, Old Greytown is mainly home to exotic migratory birds, tapirs that plod about and sleek wild cats that paw their way through the underbrush.

Occasionally, human life appears in the form of a tourist poking around the graves.

Peter Stevenson, a British citizen who works for the Inter-American Development Bank in Managua, had come in search of long-lost family ties.

Among the Masonic graves, Mr Stevenson found the headstone of Florence Edith Maud Schardschmidt, who was laid to rest in 1901 by her "heartbroken husband," Howard Schardschmidt.

Gold rush

Mrs Schardschmidt, who was only 23 when she died, was the sister of Mr Stevenson's great-grandmother. She happened to be from New Jersey, which is why she is buried in the Masonic graveyard and not in the neighbouring plot reserved for Britons.

The roots of Mr Stevenson's family tree, it turns out, are as twisted and far-reaching as the jungle vines besieging Old Greytown.

Bypassed by history? Greytown was once at the centre of trans-oceanic travel

Although Greytown was technically a British protectorate, by the mid-1800s it was under the de facto economic control of US industrialist Cornelius Vanderbilt, who sought to turn it into the starting point of the hemisphere's first trans-oceanic canal.

By 1849, Vanderbilt's Accessory Transit Company was shipping thousands of US adventurers, whose ultimate destination was gold-rush California, to Nicaragua.

Rather than brave the long overland journey from the east to the west coast of the US, these prospectors would travel along the San Juan River by ferry, trek across the remaining bit of land to the Pacific Ocean and continue their shipboard journey north to California.

Cornelius Vanderbilt saw a business opportunity in Nicaragua

In three short years, Vanderbilt's company moved more than 52,000 Americans along the San Juan River.

It was during that roughneck era that the US side of Mr Stevenson's family first came to Greytown.

"My ancestor came to Nicaragua in 1853 as a steamboat captain from New Jersey. He ran Vanderbilt's steamship company and smuggled guns up the San Juan River to (US mercenary) William Walker," Mr Stevenson says.

Greytown's heyday, brought about by the curious combination of US capitalists, British aristocrats, tenuous indigenous alliances and the occasional outlaw, was, as one might guess, short-lived.

By the middle of the 19th Century, its fate as a boomtown-gone-bust was sealed.

First the US Navy burned the city to the ground in 1854, which was not appreciated by the locals.

Second, the Treaty of Managua was signed in 1860, ceding the recently rebuilt Greytown to Nicaraguan governance and so ending several centuries of colonial management.

The third nail in the coffin came when Nicaragua lost its canal bid to Panama, effectively terminating all international interest in Greytown.

'Historical ties'

Now, as the current Sandinista government again dusts off Nicaragua's yellowing canal plans, there is suddenly renewed interest in saving this remote corner, now known as San Juan de Nicaragua.

In late May, the Nicaraguan government inaugurated a $16m (£10m) airport that is literally carved into the jungle alongside the colonial graveyards.

The Panama Canal is a crucial part of the global shipping industry

While tourism will benefit, many believe the new airport is linked to national defence, the drug war and Nicaragua's renewed canal plans.

The Sandinista government recently signed a $720,000 contract with Dutch companies Royal Haskoning-DHV and Ecorys to conduct feasibility studies on several proposed canal routes, one of which would go right through Greytown, as Vanderbilt envisioned 150 years ago.

Whatever the airport's main function may be, locals are hoping for a boost to the region's eco- and historical tourism.

The British embassy recently took a renewed interest in the area, backing programmes to support environmental education and prison reform in nearby Bluefields.

"Greytown has a very colourful history and Britain's connection with Nicaragua's Caribbean Coast spans over 300 years," says British ambassador Chris Campbell.

"The people who live on the coast value these historical ties very much and our embassy is pleased to be keeping these links strong."

Briton Peter Stevenson agrees. "This was once an important trading outpost for the British Empire, and when you see how it has become such a ghost town, it makes you nostalgic," he says.

"So for those who are interested in the history of the British Empire, this is a fantastic destination."