Could exit permit change speed up reforms in Cuba?

- Published

Mikhail Gorbachev brought unstoppable political and social change to the Soviet Union

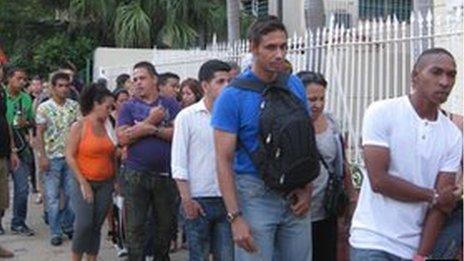

As Cuba removes the need for its citizens to obtain exit permits before travelling abroad, Alexander Zhuravlyov of the BBC's Russian Service remembers when the same thing happened in the former Soviet Union. Soon after that the Soviet political system unravelled.

In the spring of 1987, I first heard a strange story about someone among our friends getting a new "blue" service passport which had previously been reserved only for diplomats and people sent abroad on official business.

To put matters into perspective, I was then a teacher of English, with a PhD in English Literature, at one of the technical colleges in Leningrad (now St Petersburg). It was the era of perestroika, which had been launched by Mikhail Gorbachev a year before, and there was a lot of excitement about.

I was particularly excited as I had been prevented from travelling abroad for many years, and was considered politically unreliable by the KGB - which was no secret to me or my work colleagues.

The first step was to apply for a blue passport through the human resources department of my college, which I did. I informed them that I wanted to travel to the UK, to work on a book on English poetry, and very quickly they produced a passport.

So my wife and I decided to be brave and apply for an exit visa. This meant approaching the OVIR office, which handled all matters of foreign travel in the USSR. Although the OVIR was officially a branch of the interior ministry it was unofficially run by the KGB.

It was a risky move for us, as it could attract unwanted attention from the authorities.

So we collected all the required documents and gave them to a stern-looking middle-aged woman at the office. We were told to expect an answer in three to four months.

Intellectual freedom

While we waited, the stories began to circulate about more and more people, just private citizens, being allowed to travel abroad to visit their relatives and friends.

The first to travel were those whose relatives had been allowed to emigrate from the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 80s. It was an unnerving experience for a lot of them, as they had never expected to see their friends and relations again when they were leaving the country.

Then I started hearing about people like myself, young and not very young scholars, allowed to travel to Paris or London for a scientific meeting.

And then suddenly, after only a month's wait, there was telephone call from the OVIR office informing us that the visas were granted and we should come and collect them. How we travelled to Britain and saw all our friends and resurrected old ties is another story.

I believe that this relaxation of the old Soviet system of strict foreign travel controls was a crucial stage in the process of gradual, but quickening, dissolution of the order based on fear and intimidation.

Once fear was removed, the political system began to unravel quite fast. And for lots of members of the Soviet intelligentsia it also meant a new intellectual freedom.

For the supporters of the old regime it meant quite a different thing - betrayal of state secrets, liberal dissolution of the state and, ultimately, a catastrophic relinquishing of state power.

A personal note of gratitude is due to Mikhail Gorbachev, without whom all of this would never have happened.

- Published16 October 2012

- Published25 March 2024