Sao Paulo police at war with prison gang

- Published

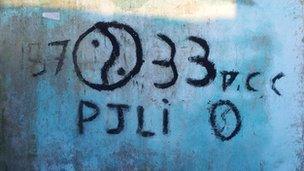

The PCC is believed to be behind a number of recent murders of police officers in Sao Paulo state

One morning in May, when Edilson Avelino de Sales arrived at the school where he worked as a security guard, five men armed with rifles and pistols were waiting for him.

He did not have the chance to use the pistol he was carrying for self-defence. He was shot many times and died at the scene.

But it was not his part-time job as a school security guard in Guaruja, a coastal city in Sao Paulo state, which made him a target.

Sales was also a police officer - one of more than 80 to die this year in what is a growing battle between the forces of law and order and the main criminal faction in this region of Brazil, the First Command of the Capital, or PCC as it is widely known.

The PCC is both ruthless and organised, and its commanders are said to sometimes issue orders for executions from within Sao Paulo's prisons.

The conflict between it and the police has escalated in recent weeks, with the murders of four police officers and 21 civilians in four different cities.

Most of the policemen were ambushed when they were off duty, often when arriving at their homes.

In a sinister pattern, hours after each police death, several civilians were killed in neighbouring areas by unidentified men in apparently random executions.

Alongside this disturbing trend is a rise in civilian deaths, suggesting that some police officers are seeking retaliation by taking the law into their own hands.

Between January and August this year, 3,109 civilians were murdered in Sao Paulo state, up 7.6% on the same period last year.

Drug trafficking

Privately, prosecutors and police in Sao Paulo believe the PCC is responsible for most of the officers' deaths, but in public the state authorities refer only to "criminal groups".

The PCC first emerged in Sao Paulo's prisons in the 1990s, with the aim of protecting inmates from abuses by the authorities.

However, it quickly expanded into an extensive criminal organisation involved in drug trafficking.

In 2006 it provoked the worst unrest ever seen in Sao Paulo, paralysing the city and resulting in the deaths of almost 500 civilians and close to 50 members of the security forces.

But in this latest stage of the conflict, it is the response of the police that is causing the greatest concern. There is an increasing suspicion that police death squads are at work.

"It is impossible to deny that there is a line that connects the deaths of civilians and policemen," said Marcio Christino, a public prosecutor working in criminal justice in Sao Paulo, who specialises in the PCC.

"These were not unrelated cases."

Spike in violence

However, Sao Paulo's public security secretary, Antonio Ferreira Pinto, has suggested that other criminals may be exploiting the situation to carry out attacks and let the police take the blame.

In response to the spike in violence, 5,000 extra policemen have been sent to the worst affected areas.

Marcelo Prado, the police commander responsible for Sao Paulo's coastal cities, told the BBC that his officers were now taking additional precautions.

A controversial elite police unit known as Rota, which is currently in the front line in the battle against the PCC, has also been deployed.

Sao Paulo governor Geraldo Alckmin has said he believes the murders of police officers are a response from criminal groups to more efficient state operations targeting crime.

He said the participation of policemen in extra-judicial killings was being investigated, but denied the existence of death squads.

"The state won't be intimidated," he insisted.

Orders to kill

Analysts also suggest that the recent rise in violence can be traced back to a hardening in police tactics directed against the PCC, hitting its capacity to sell drugs and weapons.

"After 2006, the PCC adopted a strategy of low-intensity conflict, without spectacular high-profile attacks, directed against its most effective opponent, the military police," said Mr Christino.

However, Camila Nunes Dias from the University of Sao Paulo says the recent upsurge is not a reaction from criminals to better police work but to more violent police operations.

As a result, imprisoned PCC leaders started sending messages to their operatives on the streets ordering them to kill police officers.

Prosecutors say one of those messages, sent in May, came from high-profile prisoner Roberto Soriano - known as Betinho Tirica - a PCC leader. He wanted revenge for the killing of a drug dealer by the police.

"One of the PCC's guidelines says that if a policeman captures one of its members and decides to execute instead of arresting him, then the PCC cell in the region must kill some military police," said Ms Dias.

Police under scrutiny

One of the most violent actions by the police this year against the PCC was led by the Rota unit in May.

Brazil's police force is fighting a long-running battle with criminal gangs

Five alleged criminals were killed in a shooting, while a sixth man was said to have been arrested, tortured and then killed.

Three Rota members were later arrested.

Ms Dias says her suspicion is that police intelligence, including phone tapping, is being used by Rota to ambush and kill PCC members instead of arresting them.

Sao Paulo's secretary of security declined a BBC request to respond to these allegations.

But Bruno Garschagen, a political analyst at the Brazilian think tank Millennium, says while there were moments when Sao Paulo's police act harshly, it could not be considered a policy.

"I do not believe it is happening systematically under this administration," he said.

Cycle of violence

The former National Security Secretary, Luiz Eduardo Soares, currently a professor at Estacio de Sa University, says spikes in violence have happened before in Sao Paulo, and it is too early to say if it is temporary or longer lasting.

"The root of the problem is in the lack of governability of the police along with the leniency of law enforcement officials, backed by political authorities, who tacitly authorise lethal police brutality in order to have a rigorous approach to fighting crime," he said.

He argues that tolerance of illegal police action does not reduce crime but increases it, creating "the vicious cycle of lethal brutality against the police themselves".

It is a cycle the authorities must hope will come to an end soon.