Painful search for Argentina's disappeared

- Published

"Why do they keep hurting us?" Relatives want to know why the truth has not emerged

Marcos Queipo grew up in a place where dead bodies would fall from the sky.

In the late 1970s he was a mechanic who worked in the different islands of the Parana Delta, 200km (12.4 miles) north of the capital, Buenos Aires.

"I remember seeing these military planes throwing these strange packages over the area. I did not know what they were," he says.

"But I then saw these packages floating on the river banks. When I opened them I was aghast. The packages were dead bodies."

These events happened when Argentina's last military government was in power - from 1976 to 1983.

The junta was then leading a brutal crackdown on political dissidents, a period known as the "Dirty War". Official accounts say almost 20,000 people were "disappeared" by the regime, but human rights groups say the figure is at least 30,000.

Fewer than 600 have been found and identified since then by the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team, a non-governmental scientific organisation.

The disappearances have left a deep scar in Argentine society for decades - in particular on those who had a relative taken away by the security forces at the time.

The pattern was similar for those arrested. Many were taken from their homes in the middle of the night, tortured at clandestine detention centres and then disposed of.

After years of investigations, it is thought that some bodies were destroyed with dynamite and others buried in unknown common graves, but the majority were thrown from planes into the Atlantic Ocean.

Now a new book could help provide some answers to one of Argentina's long lasting mysteries.

Written by journalist Fabian Magnotta, it is based on numerous and never-heard-before witness accounts, is pointing towards the Parana Delta as a possible mass graveyard for the disappeared.

'Death flights'

"You would see the planes in the sky, opening their hatch and dropping the packages over the area," remembers Jose Luis Pinazo, who for 40 years has driven the school boat of the area, transporting the children that live on the delta's islands.

"Sometimes you would see them every day, at other times twice a week."

"At first, we did not know what these packages carried inside. But then it became known that they were human bodies, many found on the river banks," he adds.

Mr Magnotta's book collects accounts from islanders in the delta who found bodies hanging from tree tops - in one case a body fell straight into someone's house.

"I would tell the children not to look at the bodies in the river. It was not something nice," says Mr Pinazo.

The testimonies gathered in this investigation have now been handed over to prosecutors in the current trial about the "Death Flights", in which seven people (including several former military pilots) stand accused of throwing prisoners from planes after the military seized power in 1976.

"The things I saw were not something you would talk about with others. Those were difficult times," says Mr Pinazo.

Marcos Queipo remembers that when he started finding bodies along the river, he decided to go to the police to report them.

"But they told me: 'Shut up or the same will happen to you.'"

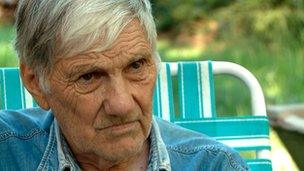

Marcos Queipo was threatened when he tried to report the disappearances

After the junta's coup, officers at all police stations in Argentina were interviewed by the military. Many have been convicted for their roles in human rights abuses that occurred at the time.

"The people in the Parana Delta are known to be very reserved and not likely to open up to outsiders. But they also kept quiet because of fear of the military," says Mr Magnotta.

Slow process

Mr Magnotta lives in the nearby city of Gualeguaychu. For years he slowly worked to gain the trust of the islanders with the help of a local friend who lives in the delta's main town, Villa Paranacito.

Many were initially wary of speaking out, but the trials and convictions of former military officers that have taken place in Argentina in recent years have given courage to those who were afraid of telling what they knew.

Both Mr Queipo and Mr Pinazo only agreed to speak to the BBC if their names or faces were not shown. But after doing the interview, they both changed their minds and accepted being identified.

"Since my book was published more and more people have come forward to give testimony of the horrible things they saw here during the dictatorship," says Mr Magnotta.

He says that now, at least twice a week, he is getting emails or calls from people who want to add information to his research.

"The publication of this investigation has helped those who were reluctant to speak before," he adds.

Hope

Families of the disappeared are watching closely to see what this new research can add to their decades-long search.

"I still have hopes of finding the remains of my son. If I ever find them it will help me enormously," says Santa Teresita Dezorzi, who at 82 is still politically active. She is the leader of the human rights organisation Mothers of May Square of Gualeguaychu.

Her son Oscar was kidnapped by security forces on 10 August 1976. He was arrested in the middle of the night, forced half naked into a vehicle, and never seen again.

He was a member of Montoneros, an armed guerrilla group which fought the military in the late 1970s.

"Of course I have thought long about the possibility that his remains are here, in the nearby delta. How can I not think about that?," she says.

At the time of his arrest Oscar had a five-month old son, Emanuel, who is now 37. As for his grandmother, the disappearance of his father is a burden he has carried all of his life.

Bodies were thrown into the delta sometimes twice a week, say residents

"I remember when I was a child that people would look at me as if they knew something I did not. Families like ours, who have lived with a situation like this, are different. We are not a normal family," says Emanuel.

Last December a court found four former military and police officers guilty of the illegal arrest, torture and disappearance of Oscar Dezorzi and three other left-wing activists from Gualeguaychu.

But for the Dezorzis, the trial produced no information on where Oscar's remains might be.

"I don't know why they still have to keep hurting us. My grandmother has done nothing wrong. I have done nothing wrong. Then why not tell us where my dad is," says Emanuel Dezorzi.

"There are many families in Argentina destroyed by this, just like us. We have gone through 37 years of not knowing. To have a relative disappeared is a wound that does not close until the person appears again."

Many people living in the Parana Delta have never spoken about the bodies falling from the skies

- Published29 April 2012

- Published5 March 2011