Bolivia-Chile railway marks 100 years at time of strife

- Published

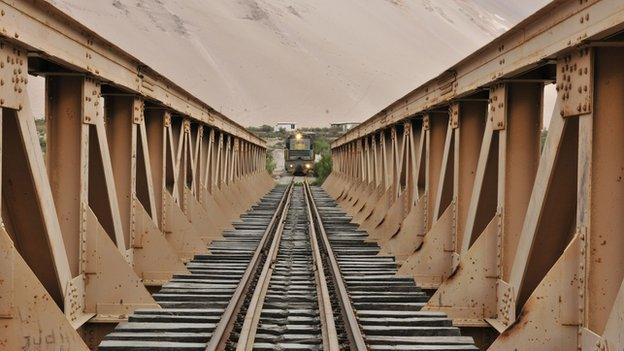

The Arica-La Paz railway reaches a height of 4,200m (13,800ft).

On its 440km it crosses some of Chile's and Bolivia's most inhospitable terrain.

Built the English firm Sir John Jackson Limited, the railway passes through seven tunnels through the Andes.

Trains travelling the route mainly transport copper, tin and wool.

Freight is now carried by lorries more often than trains, but when it was inaugurated in 1913, the railway was a key trade route.

While its heyday as a transport route is over, the railway continues to have symbolic value linking Chile and Bolivia at a time when they are quarrelling over land at the International Court in The Hague.

Chile has marked the centenary of one of the most spectacular railways in the world, a railroad that straddles the Andes and lies at the heart of the country's long-standing border dispute with Bolivia.

The Arica-La Paz railway was inaugurated on 13 May 1913, and runs from Chile's most northerly port, Arica, to Bolivia's commercial capital La Paz, 440km (273 miles) to the north-east.

Its construction was a remarkable feat of engineering.

The track rises from sea level to over 4,200 metres (13,800ft), making it one of the highest railway lines in the world.

At some points, the gradient is over 6%. It was the world's steepest train track at the time of its construction.

It winds through a landscape of desert and snow-capped volcanoes. It is split roughly half and half between the two countries, with 205km on the Chilean side of the border and 235 km in Bolivia.

The railway took seven years to build and employed thousands of workers in gruelling conditions. Many suffered from altitude sickness, sunstroke and extreme cold at night.

Over the years, sections of the railway have been washed away by the flash floods that regularly hit the Bolivian highlands.

It was closed completely in 2005 but has since been renovated, and the Chileans say their part of it is now fully operative again.

Compensation

The railway was built by Chile to compensate Bolivia for its loss of land during the 1879-1883 War of the Pacific.

Chile won the war and annexed a swathe of Bolivian land roughly the size of Greece, leaving Bolivia landlocked.

Bolivia has accused Chile of failing to properly maintain the railway

The idea behind the railway was to give Bolivia access to the sea for its exports. It cost Chile £2.75m to build - around £195m ($300m) in today's money.

The Bolivians still demand sovereignty over at least a part of their former Pacific coastline, and last month took their case to the International Court in The Hague.

To this day, the railway remains controversial. The Bolivians claim the Chileans have failed to maintain their side of it.

In January, Bolivian President Evo Morales challenged his Chilean counterpart, Sebastian Pinera, to ride the train with him "to prove that it's working".

Mr Pinera accepted the challenge but the trip has yet to materialise and it is difficult to imagine it will, given the countries' poor relations.

Those relations have deteriorated further in recent months, culminating in the decision to go to The Hague.

The Bolivians have accused the Chileans of being "the bad boy of the region" and of being "unfriendly, provocative and aggressive" for refusing to consider their sovereignty demand.

Chile has responded by accusing Mr Morales of distorting the truth when discussing the history of the dispute.

Past Glory

Monday's ceremony in Arica was therefore an all-Chilean affair, with no representatives from Bolivia.

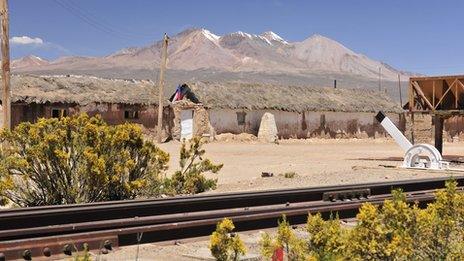

Stations have lain deserted since the passenger service closed in 1996

President Pinera took the train from Arica to the tiny Chilean desert village of Poconchile, a journey of around an hour.

There, he was greeted by dozens of schoolchildren waving Chilean flags.

He gave a speech at the station, describing the construction of the railway in the early 20th Century as "comparable only to the construction of the Panama Canal".

He said he regretted that Bolivian President Evo Morales could not be at the ceremony "but it gives me great satisfaction to show Chileans, Bolivians and the entire world that Chile has met its obligations under the 1904 treaty [with Bolivia]".

Chile would always have the door open to closer ties, he said, but would "defend the territory, sovereignty and sea that belongs to us".

The glory days of the Arica-La Paz railway are probably behind it. The passenger service closed in 1996 due to a lack of demand and there are now paved highways between Bolivia and northern Chile.

Trucks rather than trains carry most of the cargo traffic.

But symbolically, the railway is still important.

It is one of the few things that link Chile and Bolivia - two nations divided by a formidable mountain range, a fraught history and an equally troublesome present.