Was there genocide in Guatemala?

- Published

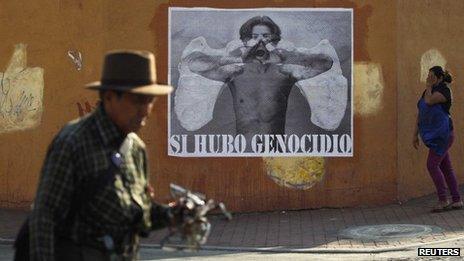

"Yes, there was a genocide," the poster reads. Guatemalans are still tussling over what happened during their 36-year civil war

Two names are synonymous with the violence of Guatemala's 36-year-long civil war.

One is Dos Erres, a village in the jungle of the Peten region which was wiped from the face of the earth by soldiers in December 1982.

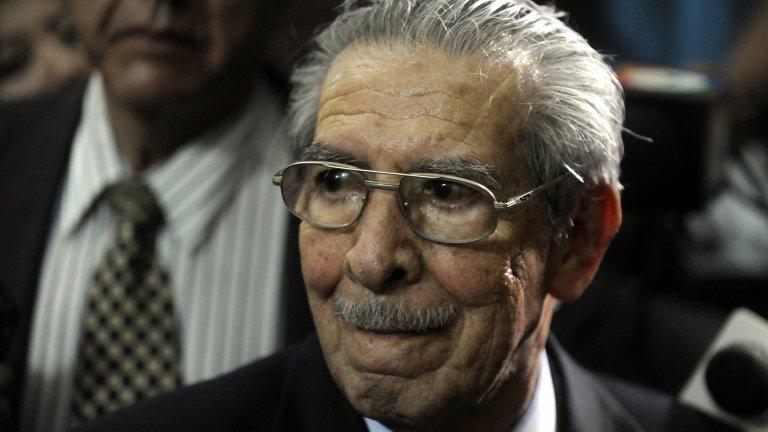

The other is Efrain Rios Montt, the de facto president and commander-in-chief of the armed forces at the time.

Today, the road to Dos Erres is long and riddled with potholes.

But for our guide, Luis Saul Arevalo, known as Don Saul, it was a far more arduous journey. Don Saul is a survivor of the notorious massacre, and the trip to the place where his village once stood brought back some very traumatic memories.

He points out grisly signposts along the way - a parcel of land where his friends once lived, the place where the school used to be, or perhaps worst of all, the site of the village well, where the army dumped the mutilated bodies of their victims.

'Nothing'

Don Saul was just 25 when scores of troops came into his village. In three days of sustained torture, rape and murder the army killed at least 200 villagers. Among them were Saul's parents, his five younger brothers and sisters, and his three-year-old niece.

Don Saul was only saved because he had gone into town with his wife.

As he surveys what is now cattle-grazing land, he remembers the day he returned to the once-thriving village after the soldiers had carried out their infamous "scorched earth" policy in the search for left-wing guerrillas.

"Two weeks after the massacre, I was able to come back here. Where children had once run and played football, where you could previously hear hymns being sung in church or see birds overhead and cattle in our pastures, there was nothing. All the homes had been burned. They left nothing."

In all, six soldiers have been tried for the crimes at Dos Erres for which they received dozens of consecutive life sentences. And yet, even though it was one of the most notorious events of his time in power, the massacre did not even appear on the list of charges against Gen Rios Montt.

Rather, the former military leader was tried for genocide related to the murders of 1,771 members of the Ixil ethnic group in another part of Guatemala.

Don Saul believes Dos Erres should have been part of the genocide case

But Don Saul believes his village should have been part of the genocide case.

"It was the bloodiest year in Guatemala's history. They can't say that there wasn't genocide in Guatemala, because we gathered up the bodies of children, pregnant women, the elderly, of young women who'd been raped. I saw little children's socks stained with blood.

"By not leaving a single human being alive in this village, they committed genocide."

Barely two weeks ago, a court agreed. There had been genocide in Guatemala, the presiding Judge Jazmin Barrios said, and the then-President Rios Montt was guilty of having planned it and ordered it.

For that and other crimes against humanity he was sentenced to 80 years in prison, sending the human rights activists and victims' families in the chamber into jubilation.

Annulled

But his legal team immediately sought to overturn the sentence. Earlier this week, they were successful.

Just days after Efrain Rios Montt was sentenced to 80 years in prison, the decision was overturned by a higher court

The ruling was annulled and the case has been reset to where it stood on 19 April.

This is the only monument to the victims of Dos Erres in Guatemala

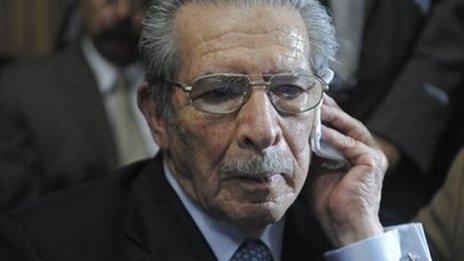

On that day, Gen Rios Montt's lawyer, Francisco Garcia Gudiel, was thrown out of the courtroom after accusing the judge of bias, leaving the former military leader temporarily without legal representation. Now a new verdict must be reached.

Mr Garcia Gudiel says the decision to overturn the genocide sentence was right for two reasons.

"The constitutional court ordered that there be no sentencing until after a series of appeal issues had been resolved. But the tribunal disobeyed that order and hurriedly issued their sentence. That's why we disagree with the verdict, on the one hand.

"And secondly," he adds, turning to a point of deep division in Guatemala, "we simply don't agree that there was genocide in Guatemala. In Guatemala there has never been genocide. We can't be compared with Rwanda or Yugoslavia or Nazi Germany."

The victims' families disagree.

Dona Maria Esperanza Arriaga, whose two daughters, aged four and six, were murdered in December 1982, says it has been hard watching the former military leader lodge appeal after appeal.

"This man has asked for so many appeals. But why didn't he give us the opportunity to appeal?" she asks, the tears rolling down her cheeks.

Sitting on the porch of her wooden shack in the Peten, she remembers those days vividly.

Forlorn

"He just ordered the army to scorch the earth. He never gave us the chance to show that we weren't guerrillas. I'd never met the guerrillas, I didn't know them."

In the municipal cemetery in the nearest small town to Dos Erres is a very forlorn-looking blue and white concrete cross next to a reconstruction of a well. Around it there is a metal fence and some tatty plastic bunting.

It is the only monument in the country to the victims of Dos Erres.

Under the terms of the Peace Accord of 1996, the government of Guatemala was supposed to build a proper monument to the dead. It never has.

As the two sides get ready for the next stage of the legal battle, once again the name Dos Erres will not feature in the list of charges against Efrain Rios Montt.

Perhaps the state of disrepair of the monument is the least of the families' concerns.

- Published21 May 2013

- Published21 May 2013

- Published13 March 2012

- Published13 March 2012

- Published2 April 2018

- Published29 July 2019