Scarred Brazil still hopeful of World Cup success

- Published

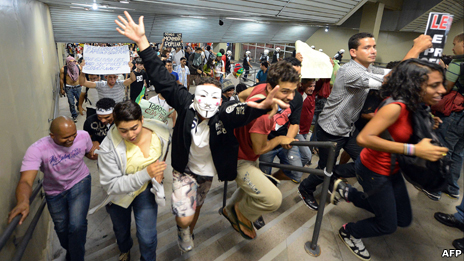

Many Brazilians say the government does not understand the "real people"

Football supporters fleeing tear gas and rubber bullets. Angry mobs torching banks and buses. Gleaming new stadiums encircled by activists.

These are images few Brazilians would have predicted they would see on the streets of their country just 10 days ago, images the organisers of the next year's World Cup could not have imagined would blight the Confederations Cup.

And yet this week, more than a million people took to the streets of 100 cities in Brazil to mark a rising wave of protest that has coincided with the country's biggest sporting event for 63 years.

The rallies, and the violence that followed, were not, however, sparked by the tournament.

It was a 20c (£0.06) rise in public transport fares that stirred passions.

But concerns over healthcare, security, rising inflation and World Cup and Olympic overspending soon became the focus - along with a profound dissatisfaction with their elected leaders, who they believed did not understand the "real people" of Brazil.

Two people have already died and there are fears more could follow, with the Brazilian media claiming the situation is "out of control".

And yet it all began so peacefully...

RIO DE JANEIRO - first use of tear gas

Riot police have used rubber bullets and tear gas to disperse Rio protesters

The cliches were rich and familiar on our arrival in this vast, sprawling city: the white sand, the seething surf and the spectacular statue of Christ the Redeemer watching over it all.

The Italian national team, Mario Balotelli and all, visited the landmarks, posing for pictures with tourists and travellers.

Even when news of the first protest in Sao Paulo broke, there was little concern or commotion.

The first suggestions that football might be involved came 24 hours before the opening match in the capital Brasilia. But even then 200 protesters burning tyres and attempting to block a road did not hint at what was to come.

At the Maracana on that first Sunday, it was a struggle to actually find the protest, although there were signs it might escalate, as 500 people - mainly students - were sent scattering in all directions by the first use of tear gas and rubber bullets as they attempted to walk towards the stadium, having gathered close to a metro station.

But having seen these protestors up close and spoken to those involved, it became clear their message was to protest peacefully. The police, however, had other ideas.

FORTALEZA - 30,000 block the road

A number of people have been injured in Fortaleza, as protesters fought running battles with police

By the time we arrived in Fortaleza the picture was beginning to change.

On our first two nights in the city the atmosphere was fraught. On the second, the local mayor was barricaded at a bank and had to be escorted out by heavily armed military police.

Our journey to the match between Brazil and Mexico laid bare the full extent of the problems. More than 30,000 people blocked the road up ahead of us.

Many were students and young people of wealthy and educated backgrounds.

Luis Carlos, 24, was one of them. He arrived at the stadium wearing a black T-shirt - the colour of protest - with a blood red hand on the front.

"We have had enough. The bus price hike was the last drop in the bucket. My father is here, my brother, my cousins. I am proud of our nation, proud of what we are saying. We need a new Brazil," he said.

The stench of tear gas filled the air near the stadium and the soundtrack was one of sirens as a number of injured police officers arrived at a pop-up hospital.

Many more protesters laid injured on the other side of the exclusion zone.

SALVADOR - Vandalism everywhere

In Salvador, demonstrators tried to block the access to the stadium ahead of the Uruguay-Nigeria match

On arrival in Salvador, the sight of a plume of black smoke rising on the horizon was impossible to ignore.

It later emerged a bus had been set on fire in the historic quarter of the city, as more than 30,000 people took to the streets.

The drive through these areas was difficult and, at times, dangerous. Sound bombs were set off to disperse the crowd, tear gas was fired without warning.

Broken glass littered the streets and vandalism was in evidence everywhere you looked.

Protesters appeared in a residential part of the city, quickly followed by the military police. Tear gas was fired and it began to seep into the open windows of those minding their own business close by.

One man stood on his balcony screaming at the heavy-handed response of the authorities. Their response was to raise their weapons at the man and laugh as they watched him flee.

Later that night the match between Uruguay and Nigeria was played against a backdrop of the crackle of rubber bullets and the deep rumbling thud of sound bombs.

The large number of students that had dominated the protest movements in the early days of the tournament was replaced by young men intent on causing trouble, many of whom had covered their faces.

Alexandre Oliveria, a young supporter of the protests, agreed to talk to me in the streets.

"It is very important for the future, for my children, my grandchildren, that a new Brazil stands up now. I am proud of this moment in our lives," he said.

WHAT NEXT?

President Dilma Rousseff addressed the nation on Friday night, and her message was one of hope and optimism to those who had protested peacefully.

The tournament is littered with rumours of general strikes around the semi-finals and the day after the final.

To the watching world, Brazil must seem like a war zone - a place only those intent on causing trouble might go.

The reality is, however, very different. The vast majority of people are warm and welcoming and utterly passionate about their national team and football, above all else.

It has been easy to avoid the protests throughout the tournament, just as it was for many who saw London burning in the summer of 2011.

At that moment, few would have predicted London would host arguably the most spectacular Olympic games of the modern age.

Brazil remains hopeful it can follow suit.

Belem

In the city of Belem - at the mouth of the Amazon River - riot police clashed with stone-throwing protesters. Demonstrators also hung protest banners and flags on City Hall.

Brasilia

In the capital Brasilia, demonstrators targeted government buildings around the city's central esplanade. Police used tear gas and rubber bullets to try to scatter the crowds.

Belo Horizonte

Police and protesters clashed in the eastern city of Belo Horizonte, which hosted a game in the Confederations Cup - the warm-up tournament for the World Cup.

Sao Paulo

The widespread demonstrations taking place across the country followed a police crackdown on smaller protests in Sao Paulo, which galvanized Brazilians to take to the streets. The city saw thousands gather once again near the city's landmark Avenida Paulista late on Thursday.

Fortaleza

At least 30,000 people rallied in the north-eastern city of Fortaleza ahead of the Confederations Cup game with Mexico this week. Brazilian police fired tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse protesters.

Salvador

There were clashes outside a football stadium in Salvador ahead of a Confederations Cup football match between Nigeria and Uruguay. Police used tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse crowds.

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro has seen some of the worst unrest. Late on Thursday, police fired tear gas and rubber bullets at groups of masked young men trying to approach the City Hall. A number of people were injured.

Porto Alegre

Earlier this week, more than 40 people were arrested in the southern city of Porto Alegre after a small group peeled away from a protest march of about 10,000 demonstrators to attack shops.