Obeah: Resurgence of Jamaican 'Voodoo'

- Published

For hundreds of years Jamaicans have been prevented by law from practising Obeah, a belief system with similarities to Haiti's Voodoo. Now, campaigners and practitioners believe they have a chance to overturn the law.

Until recently, the practice of Obeah was punishable by flogging or imprisonment, among other penalties. The government recently abolished such colonial-era punishments, prompting calls for a decriminalisation of Obeah to follow.

But Jamaica is a highly religious country. Christianity dominates nearly every aspect of life; and it is practiced everywhere from small, wooden meeting halls through to mega-churches with congregations that number in the thousands.

The island claims to have the highest ratio of churches to people in the world.

So the proposal to decriminalise what many Christians regard as black magic, a scam, or even evil, is highly controversial.

'The gift'

Obeah thrived during the era of slavery, but it has virtually died out in urban centres, where over half the Jamaican population now live.

It has survived in rural communities though, and finding an Obeah man is a relatively easy task in the hills of St Mary.

Locals point out a property that is surrounded by a corrugated metal fence, painted in bright blue and yellow. It is not exactly a discreet location for a man who takes part in illegal activity. But he is not hiding who, or what, he is.

"I'm an Obeah man, I'm not a science man, I see things," says the man, who is known by only one name: Judge.

People come to him all day long for the advice that he dispenses from his veranda.

He is in his sixties but says he first got the "gift" as a child when he predicted the death of a neighbour.

"I have nothing to hide, it's what I do, and that's my work. If you are sick I can help you; if a man puts a curse on you I can take it off. That's what I do to help," he says.

He says he can help with all manner of things, from curing illness to removing curses.

Society's good

Obeah's history is similar to that of Voodoo in Haiti and Santeria in Latin America. Enslaved Africans brought spiritual practices to the Caribbean that included folk healing and a belief in magic for good and for evil.

.jpg)

Obeah has similarities with voodoo, widely practiced in Haiti

But Obeah has been outlawed in Jamaica since 1760, so Judge and others like him are technically breaking the law. However, it has been decades since anyone was convicted.

Some politicians argue that if it is right to rescind punishments such as flogging with a wooden switch and whipping with a cat o' nine tails, the whole law should be repealed.

"We need to get rid of the Obeah act," says Tom Tavares-Finson, a senator and a barrister.

"If people want to pay for someone to cast a spell or to give them some sort of help, that's their business."

The government says it is open to discussing the issue.

"What I've suggested is that they should bring a motion for debate in the Senate on the abolition of criminalisation of Obeah, and such a debate would trigger research and discussion that would be good for the society as a whole," says Justice Minister Mark Golding.

Obeah in the city

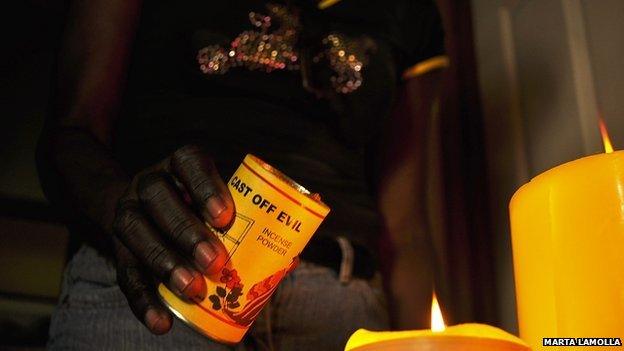

Although few people believe in Obeah in the cities, the practitioners have to come to Kingston to stock up on the potions and products they need.

One small chemist in downtown Kingston has most of the regular goods you would expect to see for sale. But it also has some surprising items on the shelves at the back: rows of candles, soaps and sprays called "go away evil", and potions that claim to either attract a new partner or stop an existing one from leaving.

"The Obeah man or woman send them here with a shopping list; we're like a pharmacist," says shopkeeper Jerome, who says he does not believe in Obeah.

But over the years the popularity of Obeah has waned and finding Obeah men and women to reveal what they do is rare.

People who use them, rarely want to talk openly about it. Many of the pharmacists who sell the paraphernalia refused to talk on the record and did not want to be identified.

Customers will mostly ignore questions about their Obeah purchases. But one young woman says she is after something that will "tie" her man, to stop him running off with other women.

"It was something my grandmother believed in. It worked then and it works now," she says.

But repealing the legislation will be tough. The Church associates Obeah with evil, others believe it is used to defraud vulnerable people, and many Jamaicans believe parliament has more important things to be getting on with, like tackling crime or improving the economy.

It is a sentiment shared by former Prime Minister Edward Seaga. He is an expert in Jamaican anthropology, and does not believe decriminalisation would make a difference.

"People don't consider it criminal. I don't remember the last time someone was arrested," he says.

"These deep beliefs are part of the folklore of the country and they aren't easy to extinguish. I don't think criminalising it one way or another will make much difference to its survival."

Judge, the practitioner in St Mary, agrees. He says he will continue what he does regardless of what the politicians decide.

"They're all idiots in politics. I don't vote for any of them, it's God I vote for. I'll just keep doing what I do," he says.

- Published27 January 2012

- Published18 November 2011

- Published26 February 2011