Fighting crime in Petare, Venezuela's toughest slum

- Published

When Venezuela decided to use the army to fight violent crime, it deployed troops to the slum of Petare. It is known as one of Venezuela's most violent areas, but change may finally be coming.

Carlos was 13 years old when he got involved in crime. Like many other youths in Petare, Carlos did it because he felt he had no other option to get what he wanted.

"I started by stealing," he says. "We would assault people coming home with their groceries, and we would take everything away from them. I did it because I wanted a motorbike and there was no money at home."

Carlos does not go into details when he explains what crimes he committed, but now, at the age of 30, he considers himself lucky.

"There used to be 16 of us working in the streets. Only three of us are still alive," he says.

In places like Petare, young people are the main victims of crime, and the main perpetrators. They are not involved in well-established gangs like those in Central America, but they are organised into small groups that fight for the control of the territory and of drug sales.

Being murdered is their biggest risk.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) labels Venezuela, external as the country with the fifth-highest murder rate in the world.

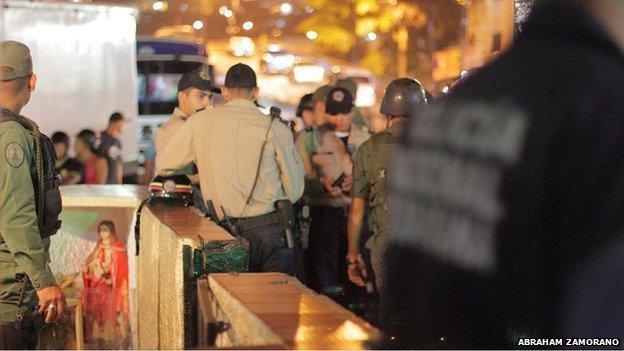

In response to what has become one of the main worries for Venezuelans, President Nicolas Maduro has sent soldiers to the streets to control crime.

Petare, the city's largest slum that grew on the steep hills overlooking eastern Caracas, was one of the first places where the army was deployed as part of the Safe Homeland initiative.

Soldiers now collaborate with policemen and have set up checkpoints throughout the neighbourhood.

Authorities say that since the launch on 13 May, homicides have gone down by 38% and thefts by 34%.

"The main aim is for people to feel truly safe and to feel that we're working for them," says Gen Marco Rojas, vice-minister of citizen security.

"This is a not a punitive plan, this is a plan with a very high social component."

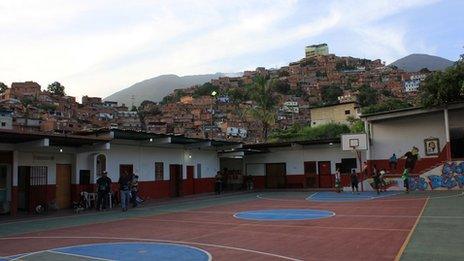

The government is promoting sport in its fight against crime

Representatives of the armed forces have held meetings with members of the community in recent weeks to hear their needs.

In Petare, these meetings have been held in pro-government centres.

One of them is the Nucleo Antonio Jose de Sucre, a community centre with large graffiti of President Hugo Chavez, who died of cancer in March after 14 years in power.

Keyla de las Rosas, one of the organisers, says she feels more protected now that the army is active.

"It's an important grain of sand," she says.

But critics say the initiative does not represent a shift from previous security policies carried out by the government.

Since 1999, the government has implemented 19 security plans, says Roberto Briceno of the Venezuelan Violence Observatory (OVV).

He says murder rates have either doubled or tripled, depending on which figures are used.

The OVV collects data from seven universities across Venezuela, and says murder figures are much higher than government figures suggest.

After years of not disclosing murder rates, this year Mr Maduro said that there were 16,000 murders in 2012. But the OVV says there were more than 21,000, a record high for Venezuela, which has a population of 29 million.

Nicolas Maduro waged a high-profile campaign for votes in Petare...

Analysts say the high levels of violence are due to a combination of factors.

Some internal factors include corruption among the security forces, a huge number of weapons available thanks to weak gun-control laws and high levels of impunity, according to InsightCrime, a think-tank that researches organised crime in Latin America.

When it comes to the wider context, Venezuela has become a transit point for drug gangs smuggling cocaine from neighbouring Colombia.

Mr Briceno says the most worrying aspect of the increasing level of violence is that the government lacks a coherent security policy and gives mixed messages.

He says there has been some progress since Mr Maduro took over as president in April.

Mr Maduro made security a priority and deployed the army to the streets. Thanks to his initiative, the National Assembly approved a much-awaited disarmament law.

He also implemented plans to use sport to promote peace.

But at the same time, he announced the creation of armed, military-trained pro-government forces known as "workers' militias" to supplement existing militias founded by Mr Chavez.

...but his rival Henrique Capriles controls the province

"There is a difference between the logic of citizen security and a logic of war," says Mr Briceno.

"In order to make progress, we need to create a professional police force, not one that is partisan and backs the government."

He says that this is especially important in the current context of polarisation following the 14 April election, when opposition leader Henrique Capriles lost by a narrow margin and alleged electoral fraud.

Even when it comes to security policy, political divisions are clear in Petare, which lies in Miranda state, governed by Mr Capriles. The mayor overseeing Petare is also from the opposition.

The government has blamed the high crime statistics on the opposition, while the opposition says the government has withdrawn funds from the local police force.

Youths like Carlos say they are clear as to why crime proliferates.

"The economic needs, the lack of access to education," he says. "The only way we had to get access was by stealing and joining criminal gangs."

Carlos left crime behind and has helped set up an organisation that aims to get more young people out of criminality by giving them material support as well as educational and psychological help.

The organisation, called El Hampa Quiere Cambiar (roughly translated as "Crime wants to change"), is looking for financial aid from the government.

Carlos is unconvinced about the army effectiveness in fighting crime, but he does not think it is necessarily a bad move.

"It is a different approach," he says. "We do our work, they do theirs."

- Published15 April 2013

- Published1 July 2012

- Published28 December 2011