City of God, 10 years on

- Published

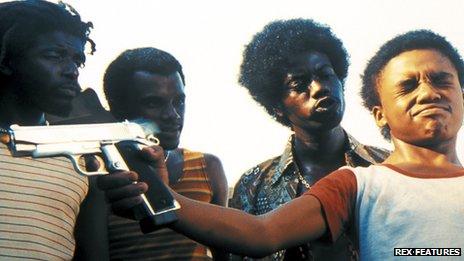

Leandro Firmino (3rd left) is still recognised for his portrayal of drug dealer Li'l Ze

Ten years after a Rio de Janeiro slum called Cidade de Deus (City of God) burst into the world's consciousness with the hit film of the same name, very little has changed for the residents and the actors have enjoyed mixed fortunes, writes Donna Bowater.

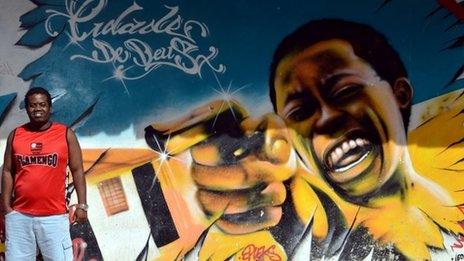

In one of the ubiquitous street-side bars in the west of Rio de Janeiro, Leandro Firmino sits sipping water dressed in the shirt of his beloved Flamengo football team. In Cidade de Deus, the community where he grew up, he knows almost all who pass by and gives them a thumbs up or a wave.

He could be any of the million who live in the city's favelas. But his famously haunting eyes are unmistakeable.

A decade after playing the terrifying drug lord Li'l Ze in the unexpected box-office success, City of God, he shows few other signs of the fame he achieved back then.

Sprawling poverty

The film, which begins in the 1960s and ends in the early 1980s, follows the lives of Li'l Ze and Rocket, a young photographer who chronicles the decline of Cidade de Deus, against a backdrop of drugs, criminal rivalry and wanton violence.

Now home to around 40,000 people, the community was originally built for families relocated to the outskirts by Rio's authorities to rid the city centre of its favelas. However, it became notorious for its gangsters, criminals and dangerous streets.

Leandro Firmino became a household name when the film was released

In one of the most memorable scenes, Li'l Ze orders a boy to choose another boy to shoot dead.

Felipe Silva, one of the children in the scene, recalls: "I was scared to death of Leandro Firmino. They kind of made me fear him so I could cry in that scene."

Firmino, now 35 and father to a 21-month-old boy, was recruited directly from the favelas to make the film, an adaptation of Paulo Lins's novel.

"It's gone pretty fast," says Firmino. "I'm surprised people remember it. It's very much alive, even among children of 11 or 12."

High-profile visit

Like many of the cast, Firmino enjoyed a high profile in the wake of the film's success, which included four Oscar nominations.

Cidade de Deus' murder rate has dropped, but poverty remains widespread

He has worked with film group Nos do Cinema (We in Cinema) and acted in several Brazilian films.

In 2011, Firmino was invited to the reception for US President Barack Obama when he visited Brazil.

"I didn't go. I had another engagement," he says. "Barack Obama's visit to Cidade de Deus was a political thing."

But while continuing to act and work in film, Firmino's life remains unaffected by one of the most enduring works of cinema to emerge from Brazil in recent years.

"Do I feel like a celebrity? No. I think it's ridiculous. It's a ridiculous word. Art is about being close to people, celebrity is about being distant," he explains. "I grew up here in Cidade de Deus. I really like it here. And God willing, I will continue to work in cinema."

He mentions that others also found success following the film, many of whom feature in the forthcoming documentary, City of God: 10 Years Later.

Love interest

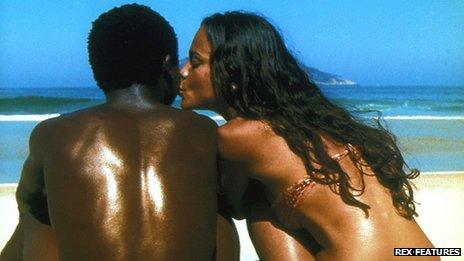

Alice Braga, who played Rocket's love interest Angelica, went on to star opposite Will Smith in I Am Legend and credited City of God with launching her career.

The film launched Alice Braga's career

"I think that beach scene, especially the one with the kiss, really helped my career because the frame of that kiss stuck in many people's minds," she tells the documentary.

"I got an agent abroad. I met many people thanks to that kiss and the picture it became."

And Seu Jorge, who played Li'l Ze's arch rival Knockout Ned, continues to be one of the best known musicians in Brazil, performing at the closing ceremony of the London 2012 Olympics.

Firmino says others have been less fortunate, mentioning Jefechander Suplino, who played Clipper, one of the impoverished thieves in the film's "Tender Trio".

He could not be traced by the producers of the documentary and is feared dead. His mother insists her son is still alive and told researchers: "He's not dead, I'm sure of that."

Rubens Sabino da Silva, who played Blackie, was arrested for trying to rob a woman on a bus in 2003. He appealed for help from the film's director, claiming he received no money for his part.

While the cast had mixed fortunes, the film has become a steadfast cultural reference for Brazil's social problems, crime and violence.

After the film was released, original novelist Paulo Lins says he feared the reaction of such a brutal depiction of Rio de Janeiro.

"I was a little scared about the repercussions of the launch [of the film]."

"It was the time of the presidential election in Brazil. Violence was the most discussed topic of the campaigns and the media talked every day about the movie. Everyone was looking for me to do interviews. I never thought I'd be so exposed in the press.

"The launch was a show of glamour, there was a lot of talk from politicians on criminality, but so far nothing has been done to effectively stop children getting into the world of violent delinquency."

Vibrant culture

But for Firmino, who returned to life in Cidade de Deus after the film, there was little in the way of public response.

Police say security has improved since they moved into Cidade de Deus

"It was normal," he says. "I lived here. Cidade de Deus has the difficulties of the favela but it always had a kind of culture.

"When I launched the film and became a public persona, it was cool, but it wasn't a big novelty because we had already seen others - musicians, some who no longer live here, and some who still live here.

"For example, if you talk about funk in Rio de Janeiro, you talk about Cidade de Deus. It was normal. It just raised morale here among people that I had produced this piece of work."

The reaction of the community to the new documentary is perhaps more telling.

Cavi Borges, executive producer, says: "There are many people in City of God who don't like the film because of the violence. When they heard we were doing a documentary, they were like: 'Oh no, not again.'

"But ours is a different form. It's a reference for Brazilian cinema; everything is City of God, City of God, City of God. It's good and bad.

In 2009, Cidade de Deus became the second favela in Rio to be "pacified" as part of a government programme to improve safety and security by increasing the police presence in poorer communities.

Police officers moved into the favela and installed a special unit to try and drive out drug traffickers. The murder rate fell from 36 in 2008 to five in 2012.

Mr Borges says he wants to change people's perception of the area.

"It's what people think Brazil is like in reality. Everyone wants to see the communities. It's like Danny Boyle's Slumdog Millionaire," which is set in the Indian city of Mumbai.

"My dream is to bring this documentary to all the countries that saw the original film."

- Published20 March 2011