Cuba's capitol: Ink wells v internet points

- Published

Raul Castro wants the Capitolio to become the new home of parliament

It took three months just to get the scaffolding up, but Cuba's biggest restoration project to date is finally under way.

The vast Capitolio, one of the most iconic buildings in Havana, is getting a multi-million dollar facelift.

Once seen as a symbol of bourgeois excess, it will become home to Cuba's Communist parliament.

The announcement that the National Assembly would move there was made by President Raul Castro earlier this year, apparently taking even the restoration team by surprise.

Majestic

But two years after the building closed its doors to the public, its long corridors, terraces and roof are at last filled with noise, dust and workmen.

Restoration work on the iconic building is expected to take years to complete

"Anyone who visits the Capitolio is impressed by its majestic size and the precious materials that were used," says architect Marilyn Mederos Perez, who admits that she was initially daunted by the restoration task.

"It's a huge challenge, because of its importance," she explains.

The Capitolio was commissioned by President Gerardo Machado after his 1925 election, for what were then two houses of parliament.

Reminiscent of the US Capitol in Washington, it came to represent President Machado's corrupt and authoritarian rule - he was dubbed the "tropical Mussolini".

"Buildings are not to blame for their past, and the Capitolio is a beautiful building," argues Havana City Historian Eusebio Leal, the head of the government office in charge of restoring the city to its former glory.

Since they were given permission to use revenue from tourism to help fund them, his staff have rescued more than 500 structures in Havana.

'Exceptional quality'

The Capitolio is one of the most challenging.

Its construction was part of a flurry of big spending in a country flush with credit from US banks; the Hotel Nacional and main highway across Cuba were other prestige projects begun at the same time.

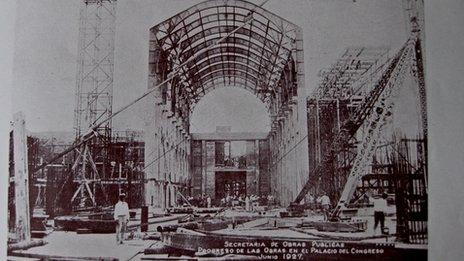

Construction on the Capitolio started on 1 April 1926

But in 1933, just two years after the Capitolio was completed and with Cuba in a major economic slump, 22 people were gunned down outside as they demonstrated against the government.

The president's subsequent resignation sparked a wave of vengeance-seeking across Havana, but remarkably the ransacking crowds largely spared the Capitolio.

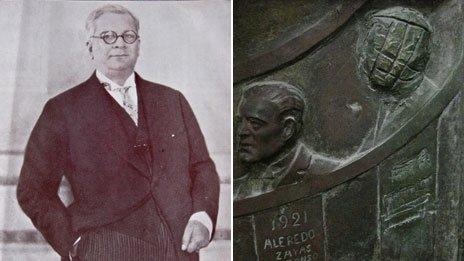

"No-one sacked the building, they only touched the face," points out Mr Leal, referring to President Machado's image which was scratched out from the bas-relief on the Capitolio's doors.

President Machado's relief was the only thing vandalised by crowds in 1933

With its classical columns and enormous, echoing salons, the Capitolio weathered the following decades relatively well compared with other structures in Havana's once grand and now dilapidated centre.

The architects involved attribute its endurance to the "exceptional" materials and fine quality of the original work - by an American construction firm.

But the restoration task remains complex.

Marked by history

Work is already under way to seal and re-cover the leaking roof that has allowed tropical downpours to warp walls and drip puddles onto the marble floors.

The walls and paintwork have suffered damp damage

Traces of the building's use since the revolution must be removed: Fidel Castro dissolved parliament until 1976, so the Capitolio instead first housed the Academy of Sciences, and later Cuba's Science Ministry.

The electric wiring has not been updated for decades, the pipes have corroded and the entire place needs to be brought into the 21st Century with air conditioning, proper fire-detection systems and security.

"There's no conflict" over the use of the building though, according to Kenia Diaz of the city historians' office.

She points out that restorers prefer to return buildings to their original use where possible, though she admits that putting politicians back in the Capitolio has made the project "a little complicated".

There do not appear to be enough seats in the chamber for a start, and the deputies' wooden desks are inset with ink-wells, not internet points.

Everything from the main podium to the elaborate lifts is embossed with the symbol of the pre-revolutionary Cuban Republic.

Nation's heritage

The Capitolio will be a radically different setting from the functional brown brick, wood and carpet of the 1970s convention centre the National Assembly uses today.

The National Assembly has little of the glamour of the Capitolio in its heyday

Instead, the Communist deputies will convene beneath weighty chandeliers and a newly gold-coated dome. They will step through marble-floored halls, lined with giant shining bronze candelabras from Tiffany's.

"I believe it will be a jewel of Havana," argues Mr Leal, unfazed by the oddity. He stresses that the Capitolio will also open its doors again to the public: Cuba's parliament only holds two sessions a year.

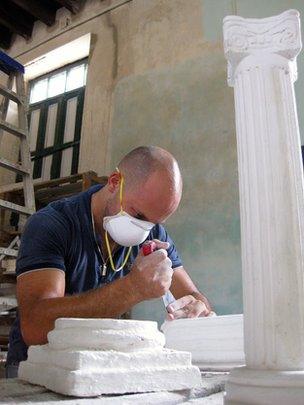

The restoration work is a slow and painstaking task

The restorers were given an initial budget for the building of $6m (£3.8m) but will not be drawn on a final price tag. They insist there is no way of costing such a "unique" project.

"Restoring a building of this kind is always an undertaking that costs millions," concedes Mr Leal.

"But you cannot neglect the demanding and splendid task of restoring heritage, even in times of poverty," he argues. "A nation's heritage is its spirit."

On the streets outside, locals tend to agree.

"It's definitely worth restoring," argues Roberto Gregorio. "Not only the Capitolio, but many buildings in Cuba. It's urgent."

"It's for us, and for humanity," Nancy Perez agrees, despite the cost.

A few steps away, the cement mixers are already whirling and stone cutters screech.

With a team of some 200, the Capitolio should be restored and ready to re-open within five years. That is roughly the length of time in which it was originally built.